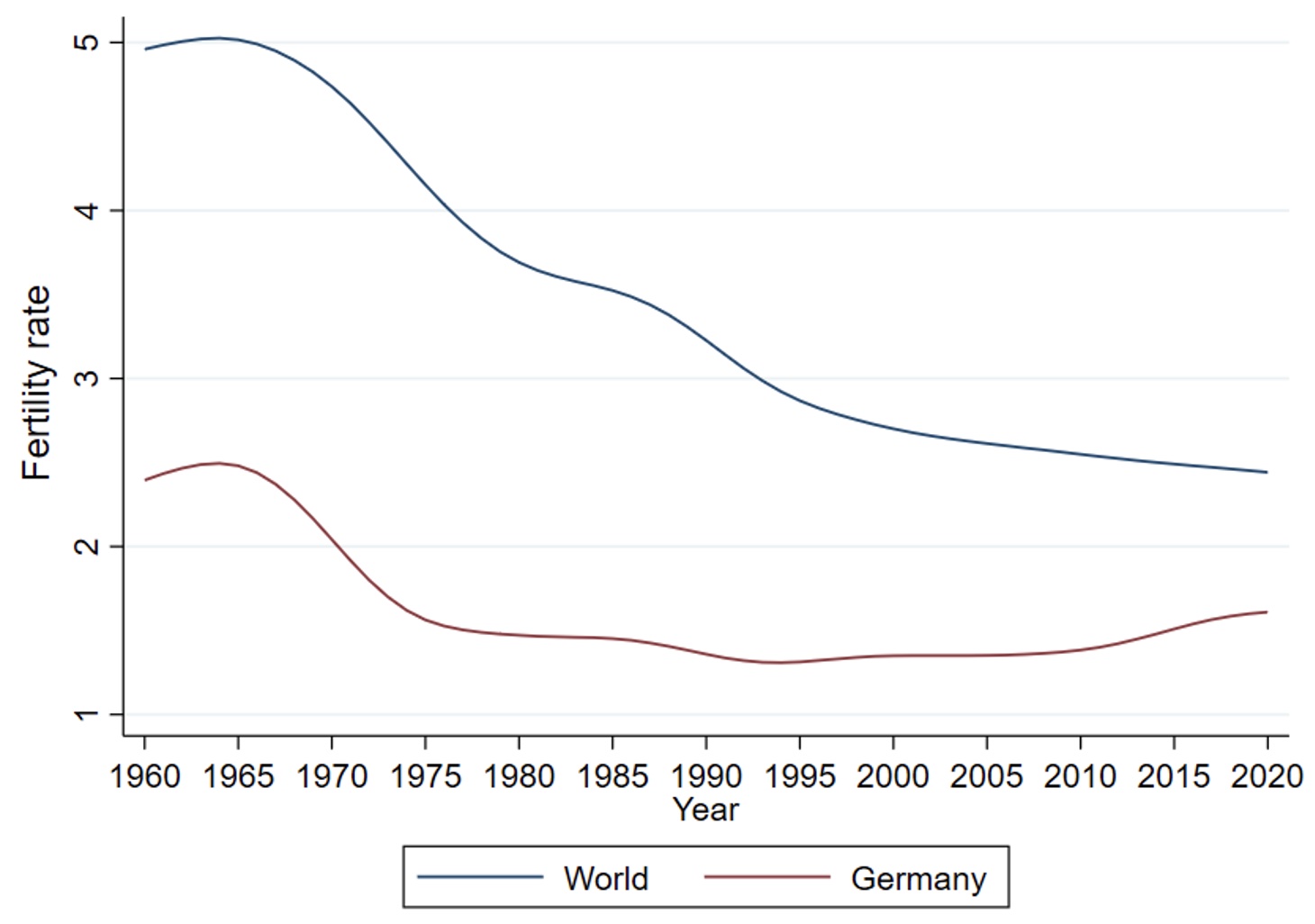

Over the previous few a long time, now we have noticed a dramatic decline in marriage and fertility charges in lots of superior economies (see Figures 1a and 1b).

The natality disaster and its demographic penalties have fostered a lot of research analysing the doable relationship between labour demand shocks and fertility decisions. In seminal works, Wilson (1996) and Wilson et al. (1986) highlighted the position performed by the secular decline of producing in reshaping household construction.

Determine 1a Evolution of marriage charges in Germany, the US, and the EU between 1980 and 2019

Notes: Information are drawn from https://ourworldindata.org/. The information on the EU and Germany comes from the Eurostat dataset. The information on the US consists of information taken from three sources: Carter et al. (2006) for the interval 1920 – 1995; the US Census Bureau (2007) for the interval 1996 – 2004; and the CDC for the interval 2005 to current.

Determine 1b Evolution of fertility charge in Germany and the world between 1960 and 2020

Notes: Information are drawn from https://ourworldindata.org/.

Supply: United Nations, Division of Financial and Social Affairs, Inhabitants Division (2019). World Inhabitants Prospects: The 2019 Revision, DVD Version: https://inhabitants.un.org/wpp2019/Obtain/Normal/Interpolated/

Earlier research have additionally proven how the liberalisation of commerce with China and different rising economies could have contributed to the rise in earnings inequality within the Western world (see Autor et al. 2016 for a assessment of the proof), with impacts that reach past the labour market (e.g. Pierce and Schott 2020). In a follow-up to their examine on the consequences of commerce on labour markets, Autor et al. (2019) doc how the destructive impacts of labour market shocks induced by growing import competitors from China have affected the marriage-market worth of males, and, in flip, marriage and fertility charges within the US due to their completely different results on the financial alternatives of female and male staff. Latest work has proven how different labour demand shocks that differentially have an effect on women and men can affect household formation and fertility behaviour (Anelli et al. 2021, Kearney and Wilson 2018). Structural financial transformations affected fertility behaviour additionally up to now. Ager and Hertz (2019) doc how on the flip of the twentieth century, the sustained shift from agriculture to manufacturing contributed to the fertility decline within the American South.

There may be additionally growing proof that the basic fashions of fertility could not clarify ultra-low fertility charges in high-income international locations, the place the compatibility of girls’s profession and household targets is now a key driver of fertility selections (Doepke et al. 2022, Billari et al. 2019, Cavapozzi et al. 2021, Bar et al. 2018, Maoz et al. 2008). Thus, low fertility settings are a very attention-grabbing context to review the consequences of labour demand shocks on marital and fertility outcomes.

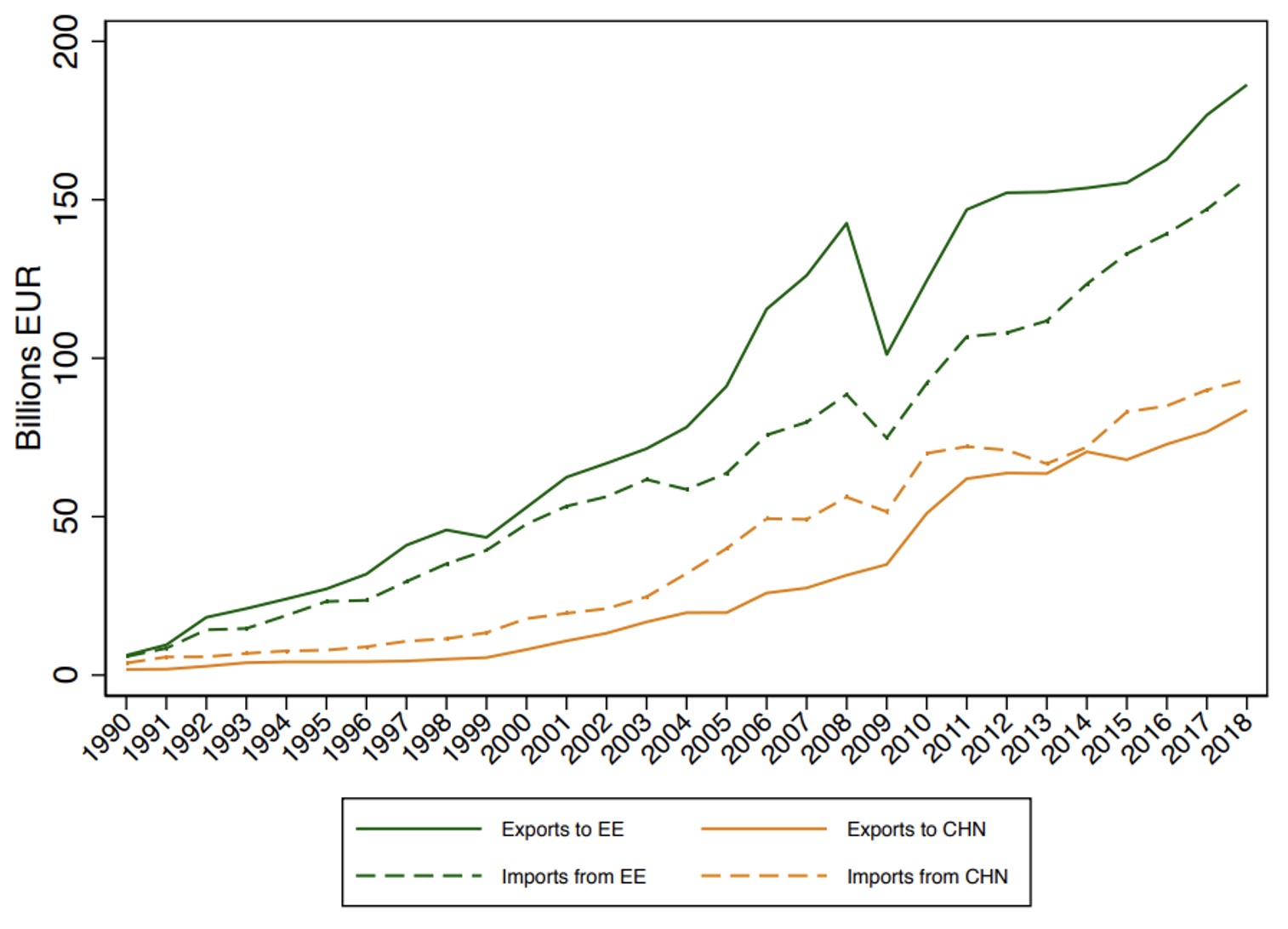

In latest work (Giuntella et al. 2022), we examine how the labour market shocks pushed by commerce with Japanese Europe and China have affected fertility and marital behaviours in Germany, a rustic which was till not too long ago in a ‘lowest-low’ fertility setting (Kohler et al. 2002, Billari and Kohler 2004, Haub 2012, Anderson and Kohler 2015).

Determine 2 Commerce between Germany and Japanese Europe and China

Notes: Commerce values are in billions of present euros. The commerce variables equal the sum of the direct and oblique (via input-output linkages) parts.

Germany had one of many lowest complete fertility charges in Europe, dipping as little as 1.2%, however then stabilising round 1.35% by the late 2000s (Haub 2012). Moreover, commerce flows with Japanese Europe and, to a lesser extent, China, have elevated dramatically within the 2000s (see Determine 2), and former analysis has proven that the consequences on the labour market outcomes have been completely different from these noticed within the US (Dauth et al. 2014, 2017). Lastly, by specializing in Germany, we are able to exploit longitudinal information on the particular person degree from the German Socio-Financial Panel (SOEP), which permits us to analyze the labour market dynamics underlying the connection between commerce integration and household decisions.

Constructing on the empirical methods proposed by earlier research analysing the labour market impacts of commerce (i.e. Autor et al. 2019, Dauth et al. 2014, 2017), we use commerce flows with different high-income international locations as devices for the commerce flows to Germany to establish causal results on labour market outcomes, the likelihood of childbirth, and marital outcomes. Our empirical technique estimates the consequences of year-to-year adjustments in publicity to commerce as decided by the preliminary {industry} of employment on fertility and marital outcomes. Due to its quantitative significance, we give attention to the variation in commerce between Germany and Japanese Europe.

According to earlier proof for Germany (Dauth et al. 2014, Huber and Winkler 2019), we discover that import and export shocks have vital results on labour market outcomes and that they function in reverse instructions. Better import competitors lowers wages, hours labored, and the chance of employment, whereas better export alternatives enhance labour market outcomes. On the web, the optimistic results of export publicity greater than offset the destructive ones of import competitors. As anticipated, the labour market impacts are pushed by the commerce relationship between Germany and Japanese Europe (relative to that between Germany and China). The commerce results on labour market outcomes are concentrated amongst low-educated people and pushed by full-time staff. This proof is in keeping with theoretical frameworks the place various kinds of low-skill labour can’t simply transfer throughout industries and therefore are affected by industry-specific import competitors and rising export alternatives. Within the evaluation by gender, we discover that the labour market results are additionally targeting males, whereas the consequences on girls grow to be smaller and fewer exactly estimated. These patterns are consistent with the proof for the US from Autor et al. (2019), highlighting destructive gender-specific employment results of import shocks.

Our findings level to the numerous results of commerce publicity on fertility behaviour. According to the proof on labour market outcomes, the affect varies with publicity to import competitors or export alternatives and with the training degree of the person. Whereas we detect non-significant results on marital behaviour (i.e. marriage, divorce, and cohabitation), the common change in imports from Japanese Europe via the interval (1991–2018) decreased fertility by 1.6 proportion factors. Following the route of the labour market responses, the consequences are concentrated amongst low-educated people and males (-1.8 proportion factors). These destructive fertility results are partly offset by publicity to better exports to Japanese Europe. Our estimates reveal that the common change in publicity to exports throughout our pattern interval led to a 1.1 proportion level improve within the chance of getting a baby, though the impact is exactly estimated solely when specializing in low-educated people. The shortage of great results on marital behaviour contrasts with Autor et al. (2019), who discover destructive results of commerce publicity on marriage charges, however is in keeping with Kearney and Wilson (2018). These variations are prone to be defined by social norms prevalent in a context like Germany, characterised by comparatively low marriage charges (Adler 1997).

Our paper speaks to a rising literature on the affect of labour demand shocks on life-course decisions (Autor et al. 2019, Keller and Utar 2022, Black et al. 2013, Ananat et al. 2013, Currie and Schwandt 2014, Kearney and Wilson 2018, Schaller 2016, Lindo 2010, Anelli et al. 2021). Our work is intently associated to 2 research on the labour market results of publicity to commerce utilizing German information. Dauth et al. (2014) discover that the unprecedented rise in commerce between Germany and the ‘East’ (Japanese Europe and China) between 1988 and 2008 brought on substantial job losses in import-competing industries, whereas areas specialised in export-oriented industries had even stronger employment positive factors. Huber and Winkler (2019) look at the position of risk-sharing between companions in mitigating the distributional results of worldwide commerce. Their findings recommend that risk-sharing considerably decreased the inequality-increasing impact of commerce. In a intently associated paper, Keller and Utar (2022) use microdata on Danish companies and staff and discover that worse labour market alternatives on account of Chinese language import competitors led to larger parental go away taking, larger fertility, extra marriages, and fewer divorces. This pro-family shift is pushed by girls of their late thirties, and the authors spotlight the position of the organic clock in explaining the findings. Our outcomes on the import results are completely different from these obtained by Keller and Utar (2022) in Denmark, who discover that better import competitors led to a ‘return’ to the household (e.g. larger fertility). Variations within the empirical technique and the context studied (i.e. insurance policies, parental leaves and subsidies for childcare between Germany and Denmark) could contribute to explaining the completely different outcomes.

General, our findings inform the general public debate on fertility charges in ‘lowest-low fertility’ settings similar to Germany in the course of the interval beneath investigation (Kohler et al. 2002). Germany’s low natality charge has been a serious supply of concern for politicians for many years. The consequences of a destructive labour demand shock due, for example, to import competitors on fertility behaviour shouldn’t be uncared for. Insurance policies tackling the demographic deficit by extending parental go away or growing baby allowances could mitigate the antagonistic demographic penalties of labour demand shocks. Our evaluation omits the doable affect of home insurance policies on the affect of labour market shifts on household decisions. Future analysis may thus examine the position of family-oriented insurance policies in mediating the consequences of labour market shocks on demographic behaviour and life-course decisions.

References

Adler, M A (1997), “Social change and declines in marriage and fertility in Japanese Germany”, Journal of Marriage and the Household 37-49.

Ager, P and B Herz (2019), “From the farm to the manufacturing facility ground: How the structural transformation triggered the fertility transition”, VoxEU.org, 16 Could.

Ananat, E O, A Gassman-Pines and C Gibson-Davis (2013), “Neighborhood-wide job loss and teenage fertility: proof from North Carolina”, Demography 50(6): 2151-2171.

Anderson, T and H P Kohler (2015), “Low fertility, socioeconomic improvement, and gender fairness”, Inhabitants and Growth Overview 41(3): 381-407.

Anelli, M, O Giuntella and L Stella (2021), “Robots, Marriageable Males, Household, and Fertility”, Journal of Human Assets 1020-11223R1.

Autor, D H, D Dorn and G H Hanson (2016), “The China shock: Studying from labor-market adjustment to giant adjustments in commerce”, Annual Overview of Economics 8: 205-240.

Autor, D, D Dorn and G Hanson (2019). “WhenWork Disappears: Manufacturing Decline and the Falling Marriage Market Worth of Younger Males,” American Financial Overview: Insights 1 (2): 161–78.

Bar, M, M Hazan, O Leukhina, D Weiss and H Zoabi (2018), “Careers and households of excessive expert girls within the age of excessive inequality”, VoxEU.org, 13 January.

Billari, F and H P Kohler (2004), “Patterns of low and lowest-low fertility in Europe”, Inhabitants Research 58(2): 161-176.

Billari, F C, O Giuntella and L Stella (2019), “Does broadband Web have an effect on fertility?”, Inhabitants Research 1–20.

Black, D A, N Kolesnikova, S G Sanders and L J Taylor (2013), “Are youngsters “regular”?”, The Overview of Economics and Statistics 95(1): 21-33.

Cavapozzi, D, M Francesconi and C Nicoletti (2021), “Gender position norms and moms’ labour provide”, VoxEU.org, 13 Could.

Currie, J and H Schwandt (2014), “Quick-and long-term results of unemployment on fertility”, Proceedings of the Nationwide Academy of Sciences 111(41): 14734-14739.

Dauth, W, S Findeisen and J Suedekum (2014), “The rise of the East and the Far East: German labor markets and commerce integration”, Journal of the European Financial Affiliation 12(6): 1643-1675.

Dauth, W, S Findeisen and J Suedekum (2017), “Commerce and manufacturing jobs in Germany”, American Financial Overview 107(5): 337-42.

Maoz, Y, M Doepk and M Hazan (2008), “Extra infants for Europe: Classes from the post-war child growth”, VoxEU.org, 08 September.

Doepke, M, A Hannusch, F Kindermann and M Tertilt (2022), “A brand new period within the economics of fertility”, VoxEU.org, 11 June.

Giuntella, O, L Rotunno and L Stella (2022), “Globalization, Fertility and Marital Conduct in a Lowest-Low Fertility Setting”, Demography, forthcoming.

Haub, C (2012), Fertility Charges in Low Start-Price International locations, 1996-2011, Inhabitants Reference Bureau.

Huber, Okay and E Winkler (2019), “All you want is love? Commerce shocks, inequality, and danger sharing between companions”, European Financial Overview 111: 305-335.

Kearney, M S and R Wilson (2018), “Male earnings, marriageable males, and nonmarital fertility: Proof from the fracking growth”, Overview of Economics and Statistics 100(4): 678-690.

Keller, W and H Utar (2022), “Globalisation, gender, and the household”, Overview of Financial Research, forthcoming.

Kohler, H P, F C Billari and J A Ortega (2002), “The emergence of lowest‐low fertility in Europe in the course of the Nineteen Nineties”, Inhabitants and Growth Overview 28(4): 641-680.

Lindo, J M (2010), “Are youngsters actually inferior items? Proof from displacement-driven earnings shocks”, Journal of Human Assets 45(2): 301-327.

Pierce, J R and P Okay Schott (2020), “Commerce liberalisation and mortality: proof from US counties”, American Financial Overview: Insights 2(1): 47-64.

Schaller, J (2016), “Booms, busts, and fertility testing the becker mannequin utilizing gender-specific labor demand”, Journal of Human Assets 51(1): 1-29.

Wilson, W J (1996), When work disappears: The world of the brand new city poor.

Wilson, W J, Okay Neckerman, S Danziger and D Weinberg (1986), “Poverty and household construction: The widening hole between proof and public coverage points”, in Combating Poverty: What Works and What Would not, Harvard College Press.