You can imagine the wrinkling of the critic’s nose. The Brexit dish served up for the UK food industry is overcomplicated, unbalanced and in parts downright nasty.

Food has always been at the sharp end of the UK’s decision to leave the EU: a 24/7 supply chain that brings in from Europe about a third of overall food consumption and is highly vulnerable to portside delays, allied to a low-margin domestic sector that relies on immigrant workers and on exports, mainly to the EU, for its profitability.

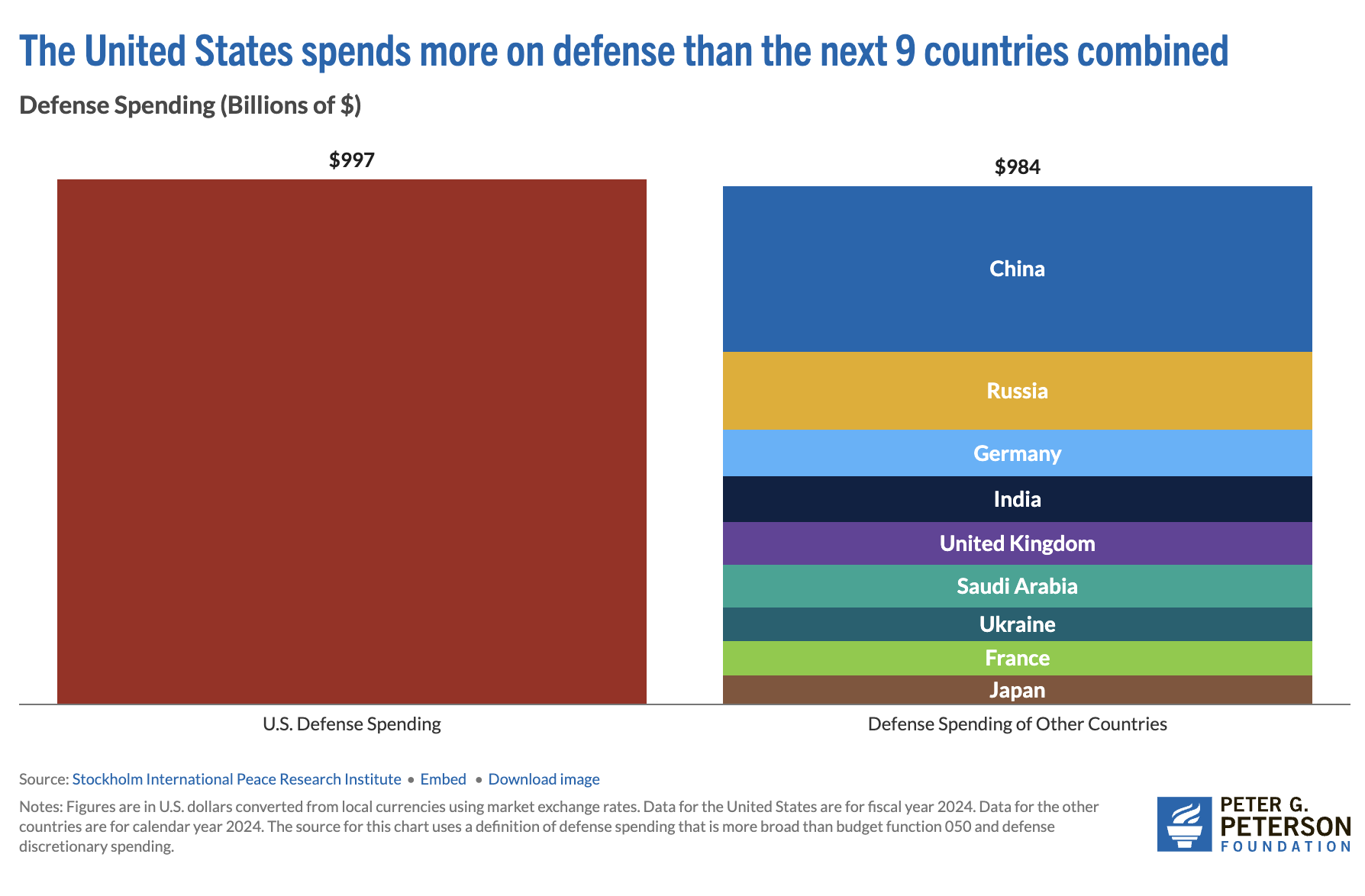

Trade figures offer misguided comfort. Global exports grew strongly in the first half of this year, according to the Food and Drink Federation, exceeding pre-Covid levels for the first time.

But the reality is headline figures mask a collapse in exporting by small businesses and restructuring by bigger companies to absorb the estimated 15 to 20 per cent higher costs of sending goods to continental Europe, said Shane Brennan from the Cold Chain Federation. While first-half exports to the EU are still 5 per cent below their 2019 level, imports from Europe are up by nearly 22 per cent.

That’s hardly surprising given that British exporters must bear the costs and hassle of health and safety checks and customs paperwork, while full border checks in the opposite direction were postponed again this year. If anything, the aggravation of selling overseas is set to worsen. From December, my colleague Peter Foster reports, new UK regulations requiring formal, paper-based veterinary attestations for animal products for export could cripple sales into Europe.

The UK has toughened rules that farm animals must be regularly inspected by qualified vets, requiring that each animal, meat product, offal or hide comes with a paper confirmation. This is impractical, as well as contrary to the promised crusade against red tape. Exports of meat, 70 per cent of which go to the EU, are likely to suffer given a lack of qualified vets to ensure compliance. Farmers, who rely on selling every part of an animal to eke out a profit, could be stuck with parts of a carcass for which there isn’t a domestic market, leading to pressure to put up prices on UK sales.

Such self-harm only increases industry frustration about the free rein given to importers, after full inbound checks were again delayed until the end of 2023. The risks of doing so are acknowledged in government controls to try to combat problems such as African swine flu. While smuggling has always been an issue, stories about maggot-ridden meat being seized at Dover highlights safety risks in a most unpleasant way — at a time when the chair of the Food Standards Agency is warning that the government’s rush to jettison EU regulations presents a risk to public health.

All this is at odds with heightened focus on UK food security since the start of the pandemic and Ukraine war. There remains a philosophical tug of war between free traders who would slash tariffs and open up the UK market to competitors and those who prioritise domestic production and protection for agriculture. “It’s left UK agri-food policy adrift,” says Tim Lang at City University’s Centre for Food Policy. “The UK is quietly exposing its own food security vulnerabilities.”

Political turmoil has dented the chances of any joined-up thinking, in a government that has rattled through four ministers for exports since July. Some stability is probably a prerequisite for meaningful progress even on the basics, such as the long-promised modernisation of archaic systems — a project about which the industry is both hopeful and deeply sceptical.

Technology is meant to underpin the imposition of the delayed import checks next year; digitisation could lessen the burden of endless paper-based export requirements; digital traceability, while unproved, could also play a role in tackling criminal wrongdoing and helping overburdened and understaffed regulators to manage food safety enforcement, argued Brennan.

Until then, the food and agriculture sectors are stuck chewing through an increasingly turgid Brexit menu: outdated and unappetising, but thoroughly predictable.