On November 4, the Bureau of Labor Statistics announced that the U.S. economy added 261,000 jobs in October, beating estimates of 193,000. Isn’t this good news? Not according to Neel Kashkari, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, who said “That tells me we have more work to do to try to cool down the economy and bring demand and supply into balance.”

To most Americans, the idea that good jobs numbers are bad economic news might seem strange. The explanation is that the Federal Reserve uses the Phillips Curve to guide monetary policy.

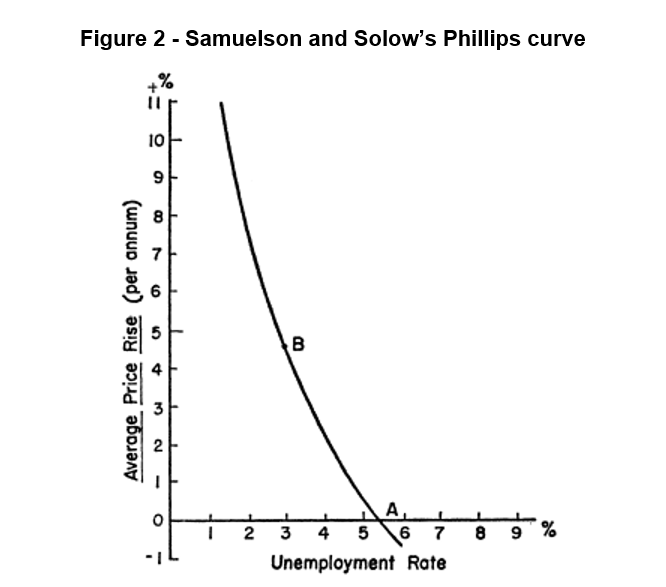

This is named after the economist A.W. Phillips who, in 1958, found a relationship in a century of British data between unemployment and the ‘rate of change of money wage rates’ (Figure 1). In 1960, economists Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow elevated this into a tool for macroeconomic management by replacing the ‘rate of change of money wage rates’ with ‘Average Price Rise’ (Figure 2). Policymakers could buy lower unemployment at the price of higher inflation or they could buy lower inflation at the price of higher unemployment.

The Phillips Curve still guides Federal Reserve monetary policy. The Wall Street Journal’s chief economics correspondent Nick Timiraos notes that,

Most economists, including [then Federal Reserve chair Janet] Yellen and others at the Fed, were guided by basic beliefs: first, that there is a direct inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment – if one goes down, the other must go up…

With her successor, Powell, in the chair, Timiraos notes, “…modified versions of the Phillips curve lived on at central banks.”

There is a problem, however: the Phillips Curve doesn’t exist. Yes, it is there in the data for a certain period, but after Samuleson and Solow, it fell victim to ‘Goodhart’s Law’: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” – or, in Goodhart’s original formulation, “Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes.”

At the Curve’s heyday as a policy tool in 1968, the economist Milton Friedman noted that “Phillips’ analysis of the relation between unemployment and wage change…contains a basic defect-the failure to distinguish between nominal wages and real wages…” An inflationary monetary policy, pursued to reduce unemployment, could, initially, succeed, but only by reducing real wages, making labor cheaper for employers to buy. But this can’t last. “Employees will start to reckon on rising prices of the things they buy and to demand higher nominal wages for the future,” Friedman wrote:

Even though the higher rate of monetary growth continues, the rise in real wages will reverse the decline in unemployment, and then lead to a rise, which will tend to return unemployment to its former level. In order to keep unemployment at its target level of 3 per cent, the monetary authority would have to raise monetary growth still more.

Inflation and unemployment could rise together.

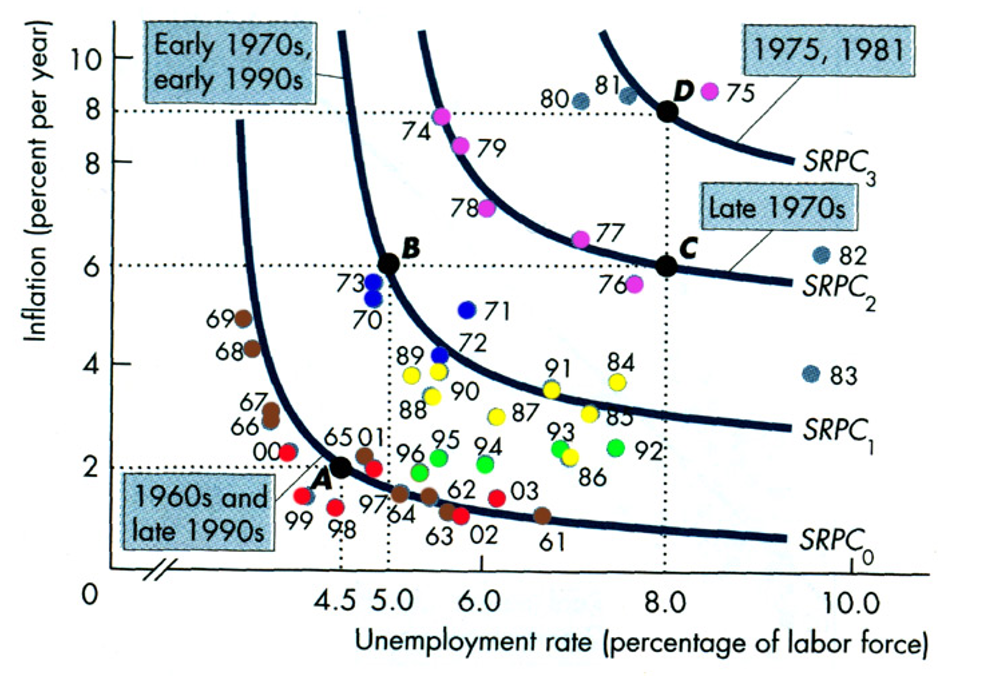

Friedman was soon proved right. The inflation rate rose from 1.6% in 1965 to 5.9% in 1970 and unemployment rose too, from 3.5% in 1969 to 6.0% in 1971. Federal Reserve chairman Arthur Burns complained:

The rules of economics are not working in quite the way they used to. Despite extensive unemployment in our country, wage rate increases have not moderated. Despite much idle industrial capacity, commodity prices continue to rise rapidly.

Through the 1970s the Phillips Curve drifted north east (Figure 3) as inflation and unemployment rose together, what was called ‘Stagflation’. By the end of the decade it was abandoned as a policy tool.

Figure 3 – The Phillips Curve on the move

Yet, somewhere along the way the Phillips Curve reemerged as a policy guide. It still doesn’t exist – fifty years after the relationship between inflation and unemployment broke down the Peterson Institute hosted a conference where they asked ‘has the relationship between inflation and unemployment broken down?’ and in 2020 economist Kristie M. Engemann asked ‘What Is the Phillips Curve (and Why Has It Flattened)?’ – but, as Timiraos notes, it guides monetary policy and explains why monetary policy makers see buoyant jobs numbers as bad news.

As Scott Sumner explained recently, America’s current bout of inflation was “caused by rapid money growth.” It will only end when this growth comes to an end (as it has). Higher unemployment may well be – in fact, probably will be – a side effect of this. But to see higher unemployment as the way we bring down inflation is to mistake the side effect for the cure. It risks the political support necessary for the cure to work and is based on a curve that doesn’t exist, the Phillips Curve, the ultimate in ‘zombie economics’.

John Phelan is an Economist at Center of the American Experiment.