Let’s discuss concerning the glass shot. (No, not the sort you pour tequila into).

United Artists

Welcome to How’d They Do That? — a month-to-month column that unpacks moments of film magic and celebrates the technical wizards who pulled them off. This entry explains how the Silent Period visible impact referred to as the “jeopardy shot” works.

As movie historian Craig Barron places it within the Criterion particular function “Visible Results in The Gold Rush,” trendy viewers tend to look again on the Silent Period as considerably archaic. And, to a level, the up to date movie-enjoyer is right. Movies made a century in the past had a lighter and fewer “subtle” toolkit. However from a special perspective, so far as visible results are involved, that’s a part of the period’s attraction. It was a time of innovation and artistic options to not possible issues.

Unattainable issues like how can we get Charlie Chaplin to stumble alongside a treacherous, Alaskan ravine with out really making him stumble alongside a treacherous Alaskan ravine?

The jeopardy shot

First launched in 1925, The Gold Rush is, appropriately sufficient, a goldmine of early particular results work, from detailed miniature work to double exposures to pretend snow. However at this time, we’re going to deal with one specific impact that happens in one of many first photographs within the movie. It’s our introduction each to Chaplin’s Tramp (right here dubbed the “Lone Prospector”) and the movie’s setting: Chilkoot Move, Alaska. The flat-footed Tramp stumbles and weaves alongside a skinny cliff face, unbothered by the immense drop that awaits him ought to he slip. It is a treacherous place whose risks appear past the discover of our bumbling hero. So, how did they pull off that shot? The manufacturing did shoot on location within the Sierra Nevada mountains. However would they actually danger Chaplin’s life like that?

How’d they try this?

Lengthy story brief:

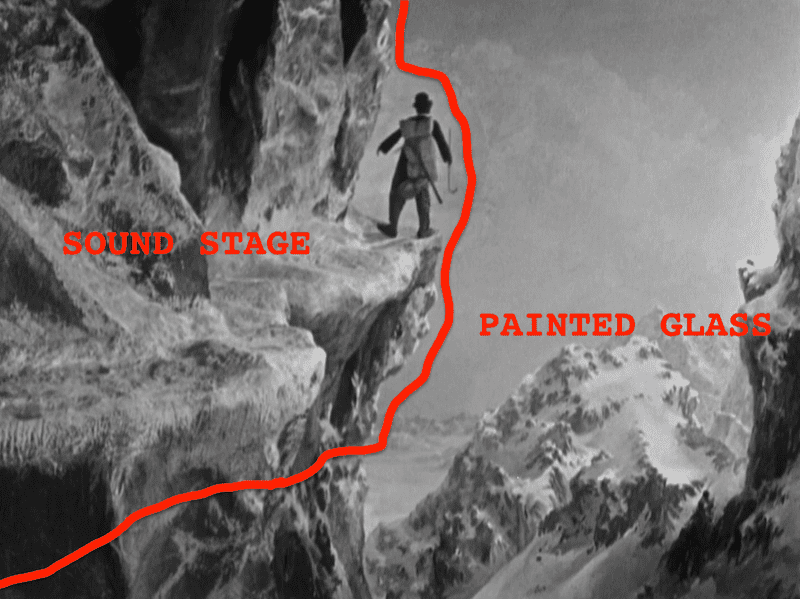

Jeopardy photographs are a variation on the “glass shot,” an early type of bodily matting that entails inserting a big painted pane of glass between the topic and the digicam so as to add, exaggerate, or change surroundings.

Lengthy story lengthy:

Glass photographs are achieved by positioning a painted glass pane sure inside a sturdy wood body between the digicam and the set. Generally the framed glass could be secured onto a rostrum or a purpose-built “shed” to provide it extra stability and safety, particularly if the shoot was outside. The shed (or a black canvas tent) additionally had the specified impact of protecting the glass towards undesirable reflections.

The glass served as a painter’s canvas, exactly aligned with some actual topographical component to promote the phantasm. The overwhelming majority of the glass was left clean, that includes solely selection painted additions. When filmed, the painted components and the live-action topics mix into one piece of pictures. The result’s a composite picture, whereby the painted portion of the glass seems to be per the live-action scene.

As Mark Sawicki lays out in his 2007 ebook Filming the Improbable: A Information to Visible Impact Cinematography, you’ll be able to simply simulate the optical physics of the trick for your self. Maintain your thumb and forefinger out as if to “crush” an object within the distance. So long as you retain one eye closed, the phantasm of an enormous hand can be sustained. In case you open each eyes, it is going to be apparent that the thing and your hand are on two separate planes. In case you alternate which eye you retain closed, you’ll discover that the connection between your hand and the thing shifts (that is referred to as parallax displacement). As a result of shifting picture cameras are inclined to solely have one “eye” (and one place), so far as the digicam is anxious, it has no depth notion and the painted object seems to be full-sized.

Two ideas of optics promote the visible impact of the glass shot: the one lens and a big depth of area, the latter of which retains the topic and the glass in focus. A 3rd phenomenon referred to as the nodal level (the optical heart of a lens the place the incoming gentle is bundled within the optical axis) explains how cinematographers can carry out easy digicam actions with glass photographs (just like the one beneath, from Chaplin’s Trendy Occasions) with out ruining the impact.

To make a really lengthy (and litigious) story brief, Norman O. Daybreak is usually acknowledged because the inventor of the glass shot course of for shifting photos. (Although, as this American Cinematographer article notes, Daybreak himself rejected “any assertion that [he] invented this system —[he] merely constructed on to it and took benefit of situations to advance an artwork within the making”). Regardless of this self-effacing remark, Daybreak’s contributions are price underlining. In spite of everything, he was probably the primary particular person in Hollywood credited for particular results work (a “cina-luminist” in 1917’s unfortunately-named Oriental Love).

A particular results pioneer whose title has been obscured via patent drama, Daybreak’s first documented use of the glass course of in motion pictures is assumed to have been within the 1907 travelogue Missions of California. As movie scholar Leslie DeLassus describes in her interview with the College of Texas, Daybreak was particularly concerned with utilizing the method to revive structure and vistas to be period-accurate, as with the 1927 movie For the Time period of His Pure Life, the place a glass shot revives the decrepit Port Arthur Penitentiary. DeLassus argues that Daybreak’s progressive use of the glass shot made spectacular scenes and set-pieces economically possible within the wake of mega-expensive Studio-Period industrial options. His work additionally paved the way in which for reasonable B-picture genres like sci-fi, horror, and journey serials so as to add manufacturing worth with out blowing their finances.

One boon of the glass shot’s simplicity was that the director might see the completed product instantly on set. Slightly than ready for weeks to see the disparate components come collectively, they might merely look via the viewfinder to see one unified picture. The glass shot is, on this approach, “the purest and least adulterated in-camera trick impact,” as DeLassus places it. The great thing about the method was that after the director referred to as lower, no additional work was needed; the impact was achieved.

One more good thing about the glass shot was that it allowed performers to simulate stunts that may in any other case be life-threatening. And this brings us to the jeopardy shot, so-called as a result of the impact might make actors seem to be in potential hazard with out really placing them in danger. So, as a substitute of risking the lifetime of beloved actor Charlie Chaplin by making him scale a treacherous cliff face, a glass shot might place the Tramp in peril with out endangering its star. The identical additionally holds for the aforementioned rollerskating sequence in Trendy Occasions, the place Chaplin glides and swoops near an unbarred ledge whereas blindfolded.

Different notable figures within the early days of the glass shot embody Ferdinand Piney Earle (Daybreak’s up to date and patent rival); the prolific Emilio Ruiz del Rio; Walter G. Corridor (who developed the glass shot off-shoot referred to as the Corridor Course of), and Ralph Hammeras, one of many first technicians to obtain an Academy Award nomination within the area of particular results for his glass photographs on 1927’s The Personal Lifetime of Helen of Troy. Hammeras’ beautiful work with glass photographs might be witnessed within the authentic The Misplaced World (1924) all through to 1963’s Cleopatra.

The glass shot was versatile, creatively liberating, and cost-effective, but it surely did have drawbacks. Essentially the most notable pitfall was the time taken up because the artist painted the glass. This could possibly be particularly troublesome if the shot occurred outside, the place altering gentle situations might invalidate the shadow work and destroy the phantasm of a seamless composite. As M. David Mullen (The Love Witch, Jennifer’s Physique) proposes on this cinematography.com discussion board, “the explanation glass photographs disappeared from use so early on was that manufacturing time was too invaluable to spend setting it up.”

One different wrinkle was that actors needed to rehearse diligently in the event that they had been prone to vanishing behind the glass-painted components. Certainly, glass photographs are probably one of many first cases of movie actors having to think about what they’re seeing. There’s a straight line between painted panes of foregrounded glass and Sir Ian McKellen getting depressed about being trapped in inexperienced display screen hell through the making of The Hobbit.

Roland Totheroh, The Gold Rush‘s cinematographer, was a frequent collaborator of Chaplin. And as Barron notes, through the Silent Period, a cinematographer was additionally anticipated to execute any and all visible results. Most results photographs needed to be achieved in-camera in addition as a result of this was a time earlier than optical printers. The jeopardy shot in The Gold Rush, the place Chaplin’s Tramp bobs alongside the precipice of a snowy cliff, was one such in-camera impact, opening up the scene and creating manufacturing worth sacrificed by capturing on a sound stage.

Regardless of fading from the highlight with the emergence of sooner processes and new applied sciences, glass photographs can nonetheless be present in various trendy movies (together with 1982’s Conan the Barbarian, 1984’s Dune, 1994’s The Shadow, and 1997’s Seven Years in Tibet).

What’s the precedent for jeopardy photographs?

The strategy of inserting painted glass between the topic and the digicam was sometimes utilized in industrial nonetheless and portrait pictures way back to the Mid-Nineteenth Century. In reality, it was throughout his employment as a nonetheless photographer for the L.A.-based Thorpe Engraving Firm within the early twentieth Century that Norman O. Daybreak first encountered the method. As Birk Weiberg relays in his 2016 dissertation “Picture as Collective: Historical past of Optical Results in Hollywood’s Studio System,” Daybreak’s colleague Max Handschiegel (who would go on to invent the “Handshiegel Colour Course of“) prompt inserting a pane of glass between Daybreak’s digicam and his topic (a constructing), to obscure an ugly pole. Portray a tree on the pane of glass to obscure the pole, Daybreak might produce a way more aesthetically pleasing picture.

Certainly, the glass shot was one other photographic trick that was grandfathered in and freely experimented with through the early days of shifting photos. It may be lumped in with a handful of nonetheless picture results, together with a number of exposures and specialist lab processing, which considerably laid the groundwork for early cinematic particular results.

Whereas this covers the extra painterly origins of glass photographs, it’s price what filmmakers did earlier than jeopardy photographs allowed cinematographers to imitate harmful units with out placing performers in danger.

As I’m certain you’ve guessed, on condition that the perspective in direction of office security through the Silent Period was an especially sarcastic shrug … the chance of plummeting to sure dying wasn’t precisely an issue for sure actors/stunt performers. Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin’s stone-faced American up to date, is essentially the most notable of those. Whereas Chaplin relied extra on bodily comedy, sight-gags, and facial expressions, Keaton’s fashion relied extra on real peril, violence, and stunt work. To sum up: if you’re watching a Chaplin movie, you hardly ever concern for his life; if you watch a Keaton movie, real peril is a part of the attraction.

To offer one evocative instance, Keaton actually did bounce from one constructing to a different in his first function movie, 1923’s Three Ages. The preliminary plan was to finish the bounce. However when he missed, he plummeted to the web ready beneath, sustaining accidents that took him out of fee for 3 days. As a substitute of abandoning the stunt, he leaned into the error and did it once more, incorporating awnings into the autumn.

As Each Body a Portray‘s tribute notes, Keaton’s strategy to filmmaking was to by no means pretend a gag. So far as Keaton was involved, the easiest way to enthrall audiences was to point out the actual deal with out slicing away. That is an perspective I’ve butted up towards a number of occasions whereas scripting this column. Every so often, you encounter a particular impact the place the filmmakers simply straight up did the factor you see on display screen (Jackie Chan’s climactic pole slide in Police Story springs to thoughts). There’s completely a bias concerned in relation to results that eschew “trickery” for the actual deal. As Norman O. Daybreak himself notes (as quoted in Stephen Prince’s Digital Visible Results in Cinema: The Seduction of Actuality): the pinnacle honchos of the Classical Studio period “didn’t consider in telling anyone about results … they didn’t wish to let the exhibitors know that this was an inexpensive image filled with fakes.”

Our trendy notion of what constitutes “pretend” filmmaking is completely different from that of the Classical Studio period. However I believe it’s truthful to say that we nonetheless have a bias in our excited about cinema that emphasizes stay motion. There’s a reverence for “sensible” results over “digital” surrogates that I’m definitely responsible of. However the awe reserved for unsimulated stuntwork, particularly unsimulated stuntwork the place bodily hurt is a part of the attraction, is one thing I’d be nice leaving prior to now.

Associated Matters: Cinematography, How’d They Do That?