Israel and France have both been flooded with mass protests in recent weeks, but the differences are striking, telling and important.

Demonstrations in Tel Aviv, Jerusalem and throughout Israel against proposed judicial reforms have been peaceful and generally orderly.

Israeli lawmakers are expected to pass the first part of the plan to overhaul courts Monday, with a bill that would bar the Supreme Court from invalidating government decisions simply because judges find them “unreasonable.”

Despite the calls for civil disobedience by some former prime ministers and other protest leaders, there has been little to no violence.

Passions are high and tempers have flared, but no one has been seriously injured, and no buildings have been burned or destroyed.

This may change over time as extremists on both sides move further apart and eschew reasonable compromises Israeli President Benjamin Netanyahu and other centrists offer.

At the moment, despite the anger and even hatred, the Israeli protests have been models of what our First Amendment guarantees: the right of the people peaceably to assemble and petition government for a redress of grievances.

Demonstrations in Paris and other French cities, prompted by the police shooting of a young Arab man, quickly turned violent — with the desecration of a memorial to French Jews deported to their deaths during the Holocaust, burned buildings and cars, rioting and injuries.

Previous French protests over economic and social issues have also included violence, as have some American protests over police killings and other racial issues.

What are the possible explanations for these differences?

Some might argue that the underlying causes of these protests justify, or at least explain, the most frequent violence in France and the United States compared with Israel.

The former protests were about unjust killings of minority citizens, while the latter are about more abstract issues of justice.

But Israelis also regard their protests as involving life-and-death issues, such as the proper role of courts in constraining military and police responses to terrorism against innocent civilians and the obligation of all citizens to risk their lives by being drafted into military service.

The stakes are high in all these protests in different parts of the world. But the level of violence is quite different.

Another possible explanation may be found in the fact that the protesters themselves are different in the different countries.

In Israel, they cross ethnic, religious and even political lines.

Although many of the protesters are secular, Ashkenazi (of European heritage), residents of Tel Aviv and anti-Netanyahu, a considerable number are religious, Sephardi (of Middle Eastern heritage), residents of Jerusalem and conservative.

Brothers, sisters, neighbors and friends are on different sides of the protests and counterprotests.

In France, and to a somewhat lesser degree in the United States, the protesters tended to be members of disaffected minority groups with grievances against the country as a whole and its institutions.

“Their goals are to destabilize our republican institutions and bring blood and fire down on France,” the interior minister said of a previous protest this year, while “Burn it all down!” has been a frequent slogan at US demonstrations.

Most of the Israeli protesters, on the other hand, are Zionists who love their country and are trying to prevent policies they believe will damage their beloved Israel.

The last thing they want to do is harm their country, though some of the protesters have advocated mischief that would hurt the high-tech economy and even the military.

Whatever the reasons, there are no justifications for the violence of the French and some American protests.

The three great democracies — the United States, Israel and France — are increasingly fractured and divided along political, religious and racial lines.

There will be more protests as the divisions get worse and as often-unpredictable events serve as provocations.

The democratic world should learn from Israel that protests can be an important aspect of democratic governance — as long as they remain nonviolent.

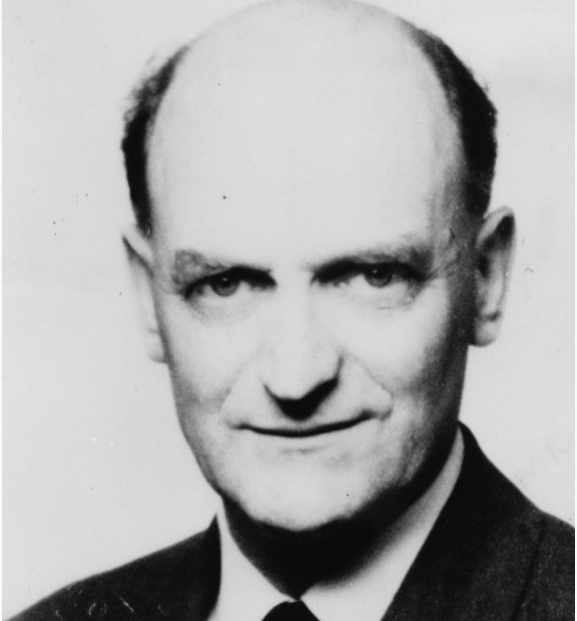

Alan Dershowitz is professor emeritus at Harvard Law School and the author of “Get Trump,” “Guilt by Accusation” and “The Price of Principle.” Andrew Stein, a Democrat, served as New York City Council president, 1986-94.