When he took the stage at a conference for “startup societies” in Amsterdam in October, 27-year-old Dryden Brown cut a rumpled figure, moving stiffly in a gray hoodie with a T-shirt poking out at the bottom.

He was there to tout his company, Praxis, which has an ambitious goal: to create a new city on the Mediterranean.

Born in Santa Barbara, Calif., Brown had never built a house before, let alone a city. A New York University dropout, he had been fired from his last job, at a hedge fund. He isn’t a charismatic speaker or an accomplished businessman. He’s big on promises and light on specifics, such as where on the 28,600-mile Mediterranean coast his city will be.

Nevertheless, he has raised $19.2 million for his project: a paltry amount in the worlds of venture capital and urban development — New York’s Hudson Yards, for example, cost $25 billion — but still a lot to fork over to a young man with no track record.

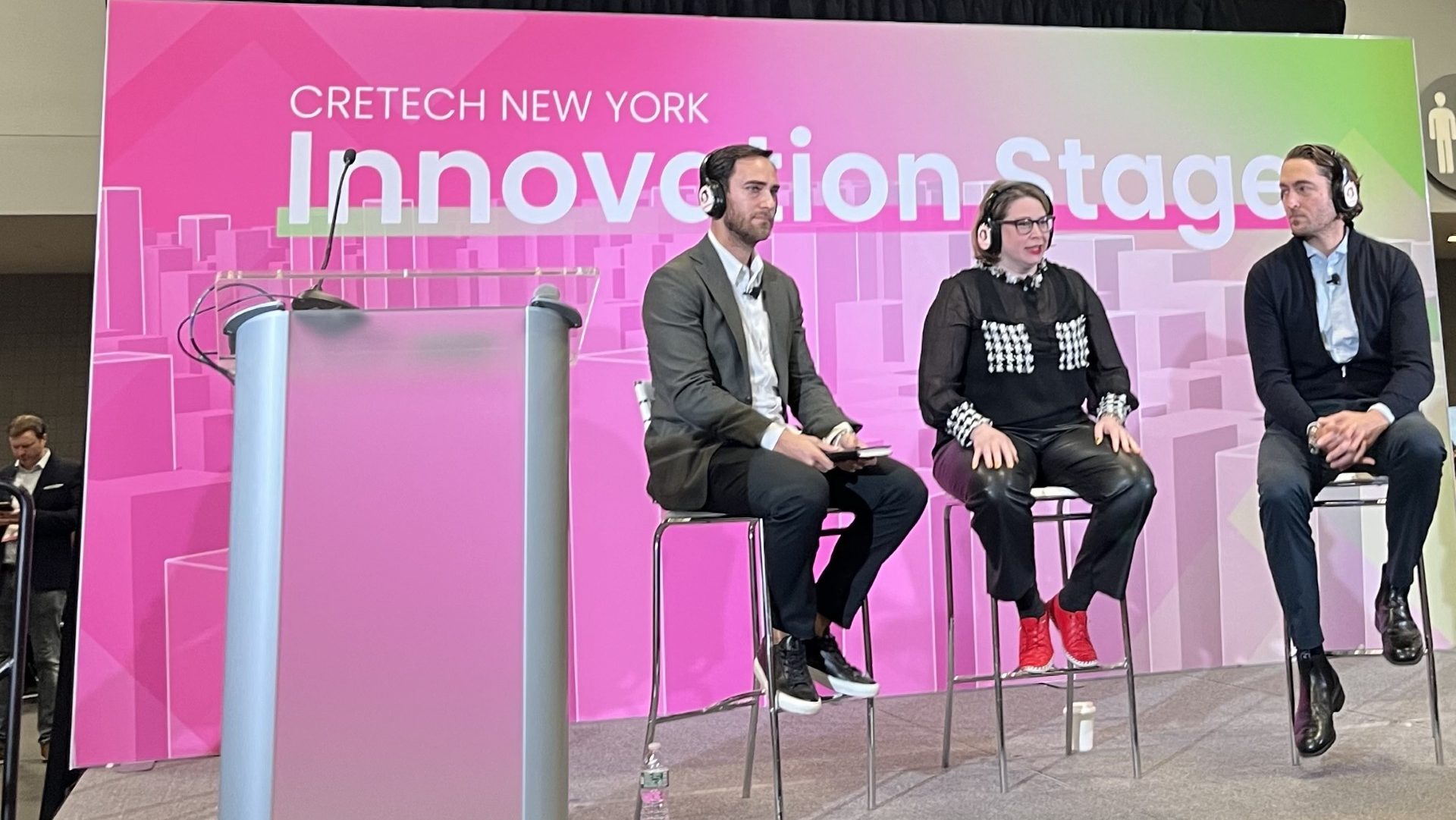

In a monotone delivery, leavened by surfer-dude inflections, Brown made some astounding claims: His team, he said, included two former prime ministers and was armed with investments from leading venture capitalists. The waiting list for membership, Brown said, was nearly 50,000 people long, with 12,000 members already interested in moving, en masse, to a “beautiful, green city” — presented in a slick rendering by Zaha Hadid Architects — starting in 2026.

Praxis takes its name from a Greek word that means putting theory into practice. And 62,000 members and prospective members would represent quite a bit of praxis, given that in July, the company listed only 431 members on an internal company roster.

Brown’s success attracting capital is in part a vestige of the crypto bubble, when easy cash and highfalutin mumbo-jumbo often went hand in hand. (The company’s 2022 Series A pitch claimed that the city would be a “cryptostate.”) The most notable venture of this era was FTX, whose founder, Sam Bankman-Fried, was running an elaborate Ponzi scheme. Praxis’ largest backer, Paradigm, was a central investor in FTX.

Praxis’ extravagant plans face daunting odds, even within the moonshot culture of tech investing, but what makes that more than $19 million truly strange is the disturbing society Brown wishes to build inside his city. “Our values inform our vision for the future,” read a slide during his presentation at the Network State Conference. “Our vision is a more vital future for humanity.”

Onstage, Brown left those values undefined, but an internal Praxis branding guide makes it clear that the company is part of a creepy internet subculture that has drawn reams of news media coverage as a fascist breeding ground within the American right.

According to several former Praxis employees who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they signed nondisclosure agreements, Brown had discussed wanting to attract tech talent to his city by introducing founders to “hot girls.” He threw lavish parties, where computer nerds rubbed elbows with the stylish members of a now-infamous demimonde that has grown up in and around New York’s Chinatown, which places shock above most other values.

Even if Brown never ends up building an eternal city, he has already built something of this moment. Praxis, a real-life partnership between puffed-up subcultures that mix mostly online, has pulled together those in the tech world who seek alternatives to liberal democracy, members of an ascendant right that rejects the premise of human equality, and a band of downtown New York scenesters who find it all a bit thrilling.

In Amsterdam, Brown described Praxis as his response to being trapped inside his apartment during COVID-19, mixed with his long-standing interest in colonial America. “Ready to join America in 1776?” reads a company pitch deck.

In 2022, Brown had been more specific about his motivation to build a city from scratch, telling a speechwriter, Webster Stone, that he got the idea for Praxis after witnessing looters break shop windows in SoHo during the protests that followed the murder of George Floyd.

According to the transcript, Brown described himself to Stone as neurotic and ambitious. He said he was home-schooled in Santa Barbara so that he could pursue competitive surfing. Exposed to the classics by his tutor, Brown read Ayn Rand and Austrian economists in high school. He said he was drawn to the idea of the charter city — a kind of special, decentralized economic zone championed by libertarians, in which a poor host country leases a piece of land to a third party, which then governs it as it sees fit. (As of 2023, the most advanced of these projects is Próspera, on the Honduran island of Roatán.)

The most prominent figure in this world is Peter Thiel, who declared in 2009 that “the great task for libertarians is to find an escape from politics in all its forms.” Since then, the billionaire Republican megadonor has backed several attempts to create corporate city-states, and he casts a long shadow over the culture surrounding these initiatives.

So it made sense that when Brown went looking for money to build his escape from contemporary New York, he found some of it in Thiel’s orbit. Pronomos Capital, a Thiel-backed city-building fund run by Patri Friedman, the grandson of libertarian economist Milton Friedman, invested in a 2021 funding round that raised $4.2 million. Two of Thiel’s associates, venture capitalists Balaji Srinivasan and Joe Lonsdale, invested in Praxis as well. But according to a person familiar with his investments, Thiel has never directly supported Praxis. Still, the widespread perception that Thiel is involved with the company has helped it build its mystique.

The biggest investment in Praxis came from the booming world of cryptocurrency, including from Paradigm, a venture capital firm best known for its $278 million stake in Bankman-Fried’s crypto exchange FTX. (Alameda Research, Bankman-Fried’s trading firm, also invested in Praxis, as did Apollo Ventures, the venture firm launched by OpenAI CEO Sam Altman.)

Praxis, cash rich, moved into a 7,500-square-foot SoHo office in May 2022. According to a former Praxis employee, Brown wore Balenciaga and drank Hallstein water (a six-pack costs $68); company parties featured charcuterie plates from Balthazar. Praxis staffed up, and Brown plotted how to introduce himself to the national stage.

The following month, the company hired Stone, the speechwriter, to help write a biographical speech about Brown, as well as the script for a short film in which Brown would walk along a beach, conversing with the disembodied voice of Mother Nature. The plan was to unveil it all at a big town hall, à la Steve Jobs. (The event never happened.)

Brown continued to spend on showy parties — many at the “Praxis Embassy,” the multifloor Broome Street loft where he lived along with several of his deputies — in an attempt to build a community of wealthy and influential young people.

Around this time, Brown started to focus his attention on “Dimes Square,” the downtown party and social media scene that achieved notoriety for its attempts to shock liberals through reactionary political postures.

Even among a crowd receptive to reactionary chic, the parties were controversial. On June 5, Praxis hosted a mixer at the Cutting Room, a lounge and venue in Midtown.

The next day, a Guardian U.S. editor named Amana Fontanella-Khan who had attended the party posted on Instagram that Praxis wanted to “create their own laws, not pay taxes and remove the poors and the undesirables.” The reason “these ghouls” were “courting the downtown club scene,” Fontanella-Khan wrote, was to solicit new members.

The July membership roster includes many bankers and tech workers, but not many models, artists or influencers. There are a few big names on the list, but they come from the worlds of tech and finance: Martin Shkreli, the ex-pharmaceutical investor who served nearly seven years in prison for securities fraud; Rob Rhinehart, the founder of Soylent, the meal-replacement company; and Max Novendstern, the co-founder — along with Altman — of Worldcoin, a controversial project that gives people cryptocurrency in exchange for their biometric data. Novendstern said he had hosted a dinner for Brown in fall 2020. Though Altman has invested in Praxis, he is not listed as a member.

“I’m not sure there’s a huge overlap between people who want to go to good parties in SoHo and people who want to live on the Mosquito Coast,” said Curtis Yarvin, a right-wing writer, referring to the Paul Theroux novel about an American inventor who attempts to create a utopia in Central America. (Yarvin stayed for several nights at the Praxis Embassy in 2022.)

Brown may now be ready to leave the Manhattan party scene behind, for a city where his ideas are more accepted.

“NYC is going the way of Chicago — second tier in every meaningful sense,” he wrote on the social media platform X on Sept. 11. “I’ll be spending more time in SF.”

Meanwhile, he continues to fundraise. A deal memo distributed to potential investors in October refers to “rumored partnerships with top tech giants” and claims “the team are now finalizing their first partnership with a Host Government,” with a move-in date of 2026. According to the memo, Praxis’ government relations team includes Stephen Harper, the former prime minister of Canada. (Harper’s consulting business did not respond to a request for comment.)

But Brown has found a chilly reception in at least one important court: According to the person familiar with Thiel’s investments, Brown has pitched multiple representatives of Thiel’s over the past year, all of whom turned him down. The source said that Thiel didn’t think Praxis was capable of executing on its ambitious plans.