Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Global Economy myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Marina Zucker-Marques and Ulrich Volz are from SOAS University of London and Kevin Gallagher is from the Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center. They are members of Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Economy project.

There are over 60 countries that desperately need debt relief. They should have already restructured but are reluctant to because we still lack a proper mechanism to deal with sovereign debt crises. The G20’s “Common Framework” has been a damp squib.

Tl;dr, the framework is tragicomically slow and doesn’t compel the major creditors to participate. And even when a deal is finally completed it doesn’t lead to enough debt relief — partly because it lets multilateral development banks like the World Bank off the hook.

Yes, private bondholders are the largest creditors to most distressed countries and have been the most reluctant to engage, but the MDBs are the second largest — and are often the biggest lenders to the poorest countries.

They are by custom considered “super-senior” to other creditors — even to other sovereign lenders — to reflect the cheapness of their loans protect their ability to keep lending to shaky countries, but this needs to change. The Common Framework at least opened up the possibility that they would share in the pain (Alphaville’s emphasis below):

Multilateral Development Banks will develop options for how best to help meet the longer term financing needs of developing countries, including by drawing on past experiences to deal with debt vulnerabilities such as domestic adjustment, net positive financial flows and debt relief, while protecting their current ratings and low cost of funding.”

But no! Although it is written right into the Common Framework — and major calls from China, other emerging economies, African countries and civil society — the MDBs and their major shareholders are hardly considering it.

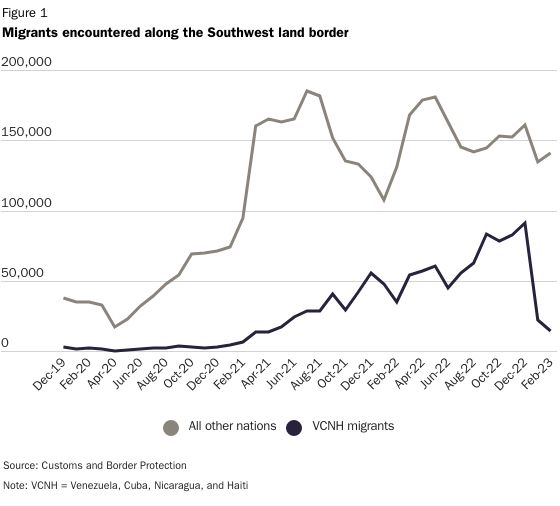

We’ve identified 61 countries that desperately need debt relief. Look at the first figure from a recent paper — 27 countries in “debt distress” owe at least half of their total external public and publicly guaranteed (PPG) debt to multilateral creditors. For 11 of those countries, the exposure is above 75 per cent.

No matter how you slice it, if development banks aren’t involved in debt relief efforts for these countries, they won’t have enough debt restructured to get back on their feet.

Of course, we get that defining inter-creditor burden-sharing is a complex exercise and that MDBs are engaged in what you might call “ex-ante” debt relief due to their highly concessional lending.

To account for this we build on the work of others to calculate a “fair” comparability of treatment (CoT) rule, which incorporates borrowing costs by creditor classes.

See the next table. Here we estimate the burden sharing among six creditor classes if the external PPG debt of 61 debt distressed countries is restructured. Here we compare two approaches to comparability of treatment: the “fair” rule that incorporates borrowing costs and the “flat rate” that applies the same present value discount to all creditors.

We provide two scenarios of debt reduction: First, a historical average of 39 per cent and, second, 64 per cent — which is same reduction adopted during the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative.

By design, under the “fair” rule official creditors give much less relief than under the “flat rate” rule. Check out the middle columns: under the “fair” rule with a 39 per cent debt reduction for the most distressed countries, MDBs (excluding the International Development Association, the World Bank’s concessional arm) would take a 24 per cent haircut (or a total of $33.3bn) and the IDA a 7 per cent haircut (or $3.5bn) given the high degree of concessionality.

It’s often under-appreciated that China’s overseas lending is also in part concessional, especially in Africa. Thus, under “fair” rule, the needed debt relief from China would also decline, though by less. Because of the higher borrowing cost from private markets, the haircut from private lenders would increase from 39 per cent to 50 per cent, or from $161.7bn to $209.3bn. They charge a premium for a reason!

The third column does the math at a HIPC-level set of haircuts at 64 per cent.

These are big numbers. But as we show in our report, if relief was provided only to a group of 41 IDA-eligible countries (and Small Island Developing States facing sovereign debt distress) then MDBs would have to shoulder losses of only $10bn — helping to achieve an overall debt write-off of $55bn, $27bn of which would have to be covered by private creditors.

Infringing on the super-seniority of development banks is obviously a touchy subject, especially at a time when their lending needs to be scaled by orders of magnitude to meet our development and climate goals. MDBs are able to provide countries with cheap loans because of their strong credit rating, which should be preserved at all cost.

But you can’t lend to countries that can’t borrow. The earlier the MDBs engage on debt relief the less costly it will be in the future. Here are three ways to finance the debt relief:

First, pony up into the Debt Relief Trust Fund. The fund still stands from the HIPC days and pools resources from international financial institutions and donors, allowing for more comprehensive debt relief efforts. Setting aside a dedicated portion of funding in each IDA replenishment for debt relief efforts is a shovel-ready option.

Second, increase MDB equity. With more equity through a capital increase, SDR-linked issuances, or Sustainable Future bonds, a portion of precautionary balances could be made available for debt relief.

Finally, an international financial transaction tax (IFTT) could foot the bill, help temper unsustainable capital flows and generate revenue for debt relief at the same time. Yes, this has been discussed seemingly since the dawn of time and never gone anywhere, but needs musts etc.

The hard truth is that including MDBs in debt relief will be crucial to solve the mounting debt crisis. Equitable creditor burden-sharing is imperative. and many of these countries simply don’t have enough other liabilities to restructure without accepting that their super-seniority sometimes needs exceptions.