Kameleon007

Long-term government bonds are looking increasingly attractive. The key question in my mind is whether regular bonds or inflation-linked bonds are the better buy, and this will depend on the outlook for long-term inflation expectations. Long-term breakeven inflation expectations currently sit just above 2%, which seems low in the context of the long-term inflation rate and the current inflation picture. As I argued in ‘LTPZ: Long-Dated Linkers Look Good For 2023‘, there is a strong case to be made for locking in real yields of around 1.7%. However, I also see a growing threat of another short-term deflation scare as money supply continues to collapse, suggesting that regular bonds could outperform. The Vanguard Long-Term Treasury ETF (NASDAQ:VGLT) is well placed to benefit from this.

The VGLT ETF

The Vanguard Long-Term Treasury ETF seeks to track the performance of a market-weighted Treasury bond index with a long-term dollar-weighted average maturity. The fund invests by sampling the index, meaning that it holds a range of securities that, in the aggregate, approximates the full index in terms of key risk factors and other characteristics. The current weighted average yield to maturity is 4.0%, with an average maturity of 23.2 years and a duration of 16.2 years. The VGLT is the smaller of the two ETFs, with USD4bn in assets versus the TLT’s USD28bn, although the former has seen a surge in inflows over the past two years. The VGLT also charges a minimal expense fee of 0.04%, which is lower than the iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (TLT), which charges 0.15%.

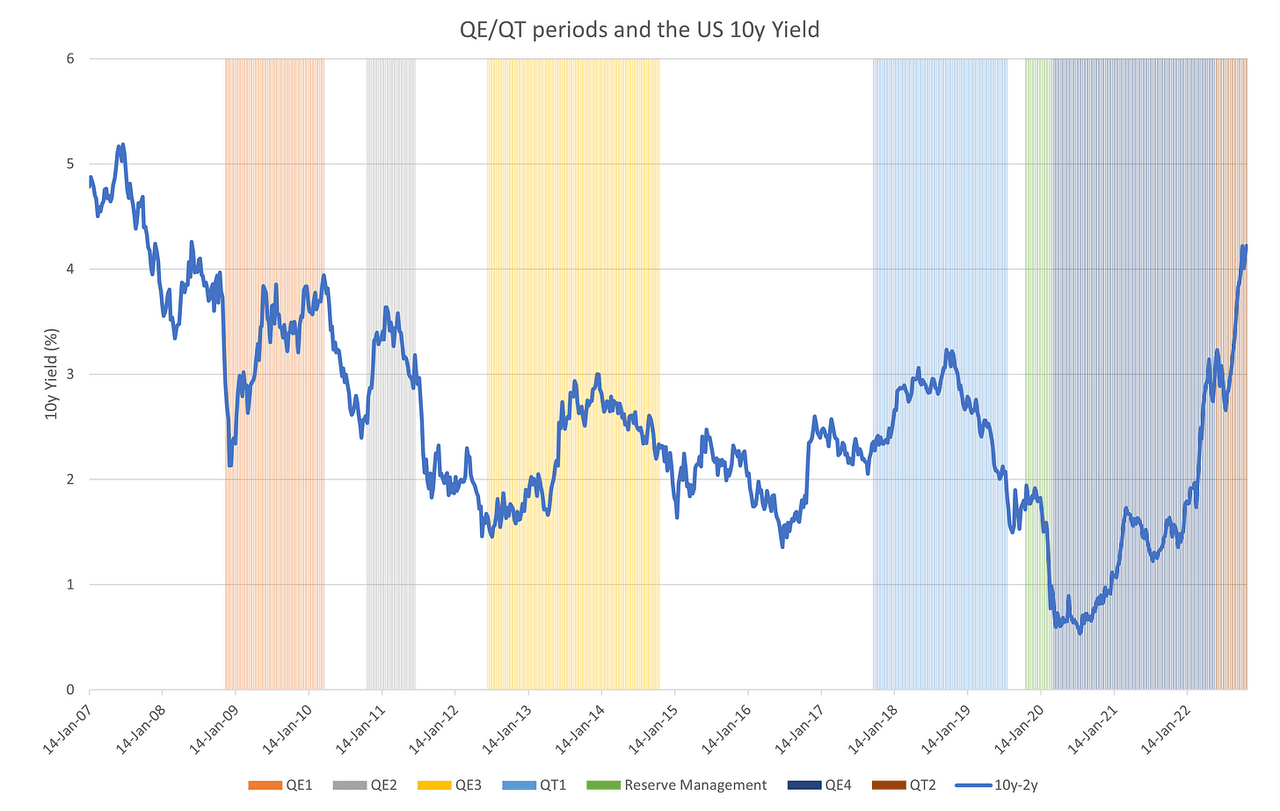

QT Should Be Bullish For Bonds

The Fed’s contraction of its balance sheet, which it is doing by letting existing bonds on its balance sheet, is actually creating the conditions for a deflationary shock, which could see private investors flock to the bond market. The Fed’s involvement in the bond market over the past 14 years has had a counterintuitive impact on bond yields. For instance, as the chart below shows, periods of quantitative easing have tended to result in higher yields, while, with the exception of the latest episode, periods of quantitative tightening have resulted in lower yields.

UST Yields Vs Fed Policy (Macroisdead.com)

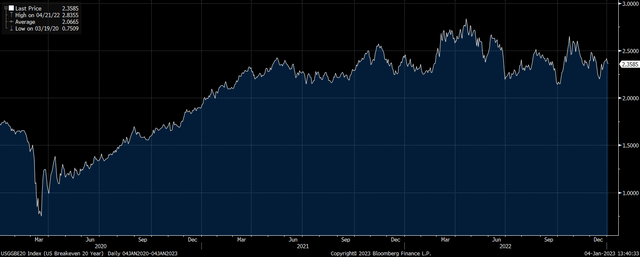

The reason for this is that the direct impact of Fed bond purchases or sales has been outweighed by the impact of private sector demand. When the Fed has engaged in QE, inflation expectations have risen due to the anticipation of increased liquidity. In contrast, when the Fed has engaged in QT, fear of tighter liquidity has driven down inflation expectations and made bonds more attractive. This is where we are today. While the Fed’s QT is directly negative for bonds, the impact of lower inflation expectations is highly positive. This can be seen in the 20-year breakeven inflation expectations rate, which has fallen from a peak of 2.9% in April 2022 to just 2.4% today.

U.S. 20-Year Breakeven Inflation Expectations (Bloomberg)

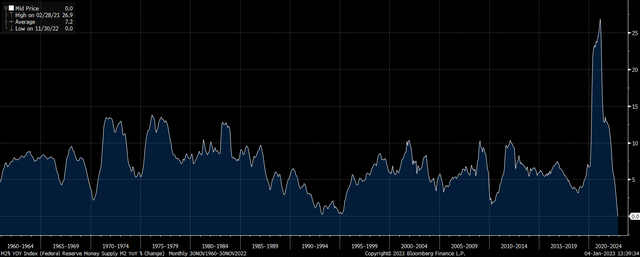

The Rising Risk Of Another Deflationary Shock

While 2.4% average inflation over the next 20 years seems on the low side based on the average seen over the past 10 and 20 years, we cannot rule out another crash in inflation expectations. We have seen a collapse in U.S. money supply over recent months, with M2 growth now running at 0% y/y, its slowest pace on record. It is almost certain to turn negative over the next few months as private credit growth fails to offset the impact of shrinking base money.

M2 Money Supply Growth (Federal Reserve, Bloomberg)

Furthermore, commodity prices continue to edge lower, with the Bloomberg Commodity Complex back to its slowest level in a year, having fallen 23% from its June peak.

Commodity Complex (Bloomberg)

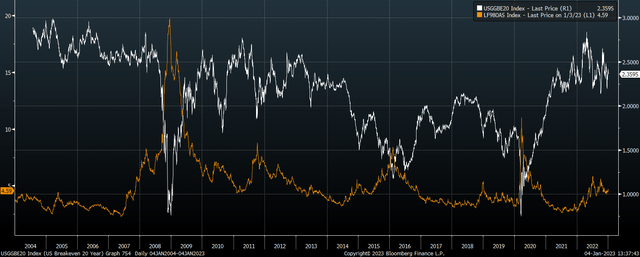

The key determining factor as to whether we see a crash in inflation expectations of the kind seen in 2008 and 2020 will be the behavior of corporate credit. Inflation expectations are incredibly closely linked with credit spreads, as rising corporate defaults both undermine money supply and, more importantly, raise demand for safe haven assets. If we see another spike in credit stress as we saw in 2008 and 2020, a crash in inflation expectations and bond yields would be highly likely.

20-Year Breakeven Inflation Expectations Vs High Yield Corporate Credit Spreads (Bloomberg)

Summary

Long-term government bonds are looking increasingly attractive, and the VGLT offers a low-cost option for benefitting from any renewed deflationary shock. While the Fed remains a net seller of Treasuries, previous occasions have not prevented bond yields from falling as private sector demand has been a more important factor. A deflationary shock is looking increasingly likely given the collapse in money supply growth and falling commodity prices. Any spike in corporate default risk would likely see inflation expectations crash and cause a stampede into long-term government bonds.