© Reuters. FILE PHOTO: U.S. President Joe Biden hosts debt limit talks with U.S. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) in the Oval Office at the White House in Washington, U.S., May 22, 2023. REUTERS/Leah Millis/File Photo

By Jarrett Renshaw, Richard Cowan and Trevor Hunnicutt

WASHINGTON (Reuters) -Democratic and Republican negotiators struggled on Friday to reach a deal to raise the U.S. government’s $31.4 trillion debt ceiling, with a key Republican citing disagreements over work requirements for some benefit programs for low-income Americans.

Time is running short for Democratic President Joe Biden and Republican House of Representatives Speaker Kevin McCarthy to reach an accord to raise the federal government’s self-imposed borrowing limit and avert a potentially disastrous default.

Negotiators appeared to be nearing a deal to lift the limit for two years and cap spending, with agreement on funding for the Internal Revenue Service and the military, years while capping spending on many government programs, according to a U.S. official.

But an administration official briefed on the talks said they could easily slip into the weekend.

The two sides remained at loggerheads over a Republican push for new work requirements for some anti-poverty programs.

“We have made progress,” lead Republican negotiator Garret Graves told reporters. “I said two days ago, we had we had some progress that was made on some key issues, but I want to be clear, we continue to have major issues that we have not bridged the gap on chief among them work requirements.”

A failure by Congress to raise its self-imposed debt ceiling in the coming week could trigger a default that would shake financial markets and send the United States into a deep recession.

“We know it’s crunch time,” McCarthy told reporters at the Capitol on Friday. “We’re not just trying to get an agreement, we’re trying to get something that’s worthy of the American people, that changes the trajectory.”

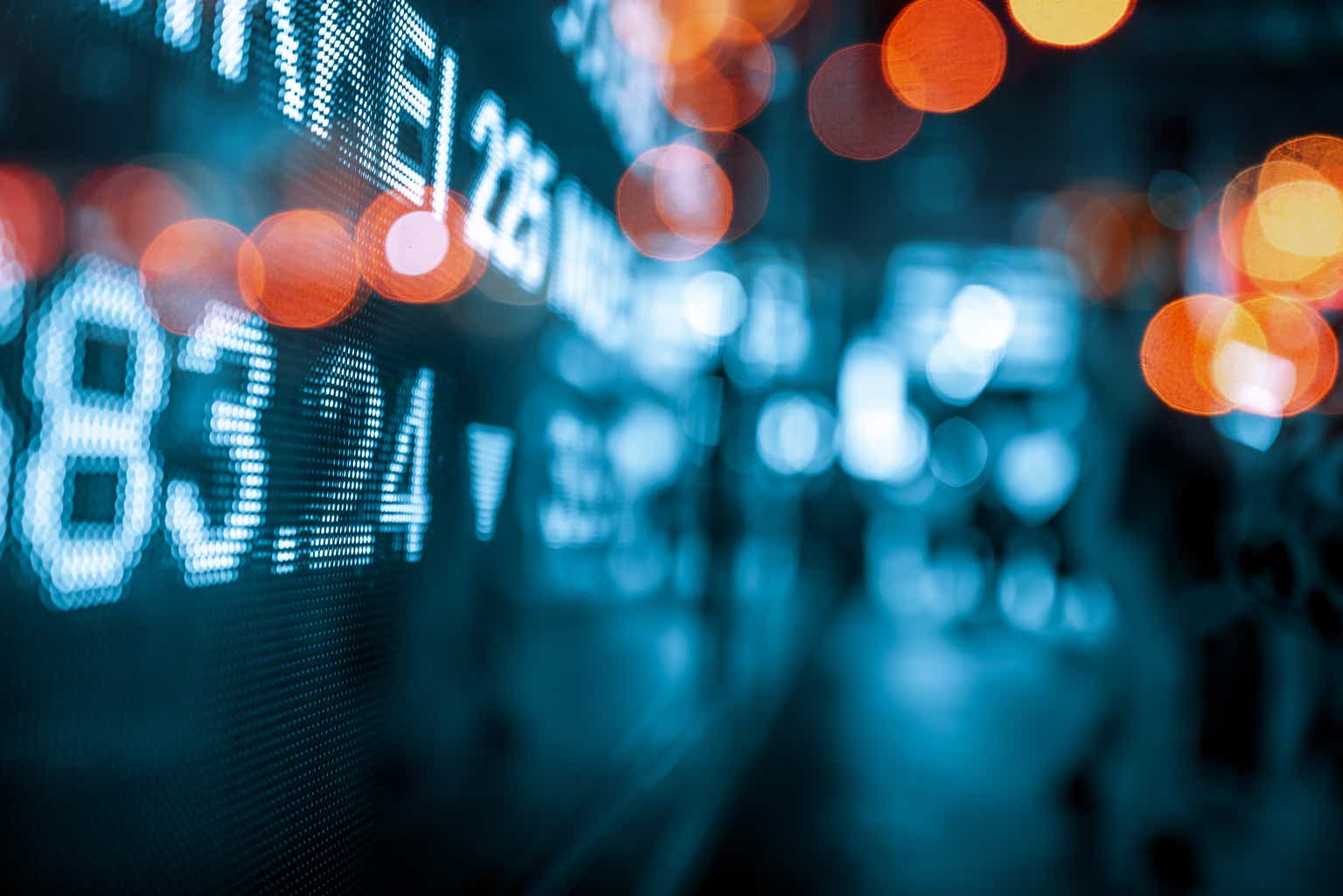

Wall Street’s main indexes rose on Friday as investors hoped for progress in the negotiations. The was set to snap a five-day losing streak, while the Nasdaq touched its highest level since mid-August earlier in the session.

Even if they succeed in reaching a deal, leaders from both parties will likely have to work hard to round up enough votes for approval in Congress. Right-wing Republicans have insisted that any deal must include steep spending cuts, while Democrats have resisted the new work requirements for benefit programs.

The deal under consideration would increase funding for military and veterans care while essentially holding non-defense discretionary spending at current year levels, said the official, who requested anonymity because they are not authorized to speak about internal discussions.

A two-year extension would mean Congress would not need to address the limit again until after the 2024 presidential election.

The deal might also scale back funding for the IRS, the official said.

Biden paid for his signature legislation, the Inflation Reduction Act, in part by committing $80 billion in new funding for the IRS to target wealthy Americans and generate $200 billion in new tax revenue. The money was designated mandatory spending, which, like social security, protects it from the annual appropriations process.

The deal being considered would shift that money to discretionary funding, making it subject to the annual appropriations process and placing its future in jeopardy, according to a U.S. official.

The White House is working on a way to preserve the effort to target wealthy taxpayers, even if the money is moved, the official said.

The deal would boost military and veterans spending to levels proposed by Biden earlier this year, a second U.S. official said.

BIPARTISAN DEAL

Each side will have to persuade enough members of their party in the narrowly divided Congress to vote for any eventual deal.

“The only way to move forward is with a bipartisan agreement. And I believe we will come to an agreement that allows us to move forward and that protects the hardworking Americans of this country,” Biden said on Thursday.

The Treasury Department has warned that it could be unable to cover all its obligations as soon as June 1, but also has made plans to sell $119 billion worth of debt that will come due on that date, suggesting to some market watchers that it was not an iron-clad deadline.

The standoff has unnerved investors, pushing the government’s borrowing costs up by $80 million so far, according to Deputy Treasury Secretary Wally Adeyemo.

Several credit-rating agencies have said they have put the United States on review for a possible downgrade, which would push up borrowing costs and undercut the United States’ standing as the backbone of the global financial system.

A similar 2011 standoff led Standard & Poor’s to downgrade its rating on U.S. debt.

Most lawmakers have left Washington for the Memorial Day holiday, but their leaders have warned them to be ready to return for votes when a deal is struck.

House leaders have said lawmakers will get three days to ponder the deal before a vote, and any single lawmaker in the Senate has the power to tie up action for days. At least one, Republican Mike Lee, has threatened to do so.