This article is an on-site version of our Trade Secrets newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Monday

Hello. Trade Secrets comes to you this week from New Delhi, where I’m based as FT South Asia bureau chief. Indians are closely watching the UK Conservative leadership contest, buoyed by the strong likelihood that Rishi Sunak, the son of Indian immigrants who was beaten by Liz Truss in the last contest, will soon replace her as prime minister.

(NDTV, a news channel, recently ran an on-screen fever chart titled “Rishi on a roller-coaster”, purporting to show Sunak’s revived chances of becoming leader.)

As Britain muddles through yet another crisis, today’s newsletter examines the fate of its keenly awaited post-Brexit pact with India, which the UK hopes will boost trade between the countries over the next decade. Charted waters will be on air freight and its pandemic-driven rise in significance in the global supply chain.

Email me at [email protected]. Alan will be back in your inboxes next week.

The long and winding road to a UK-India trade deal

It’s Diwali today, and residents here are splurging on festive clothes, sweets and parties. Notwithstanding a ban on setting off firecrackers in the capital, smoke from festive celebrations here and across northern India are expected to envelop New Delhi in smog on October 25, in what is typically one of the year’s worst days for air quality.

For trade boffins, Diwali was also meant to be the deadline by which India’s prime minister Narendra Modi and his then-counterpart Boris Johnson promised they would have concluded most of the talks on a “comprehensive and balanced” free trade agreement.

The FTA, if agreed, would be a big one for India, which recently overtook the UK as the world’s fifth-largest economy. Modi’s government is on an FTA spree, having signed trade pacts since last year with Mauritius, the United Arab Emirates, and recently reopened negotiations with the EU.

For both India and Britain, the trade deal will have a strong geopolitical element — part of the two governments’ push for more geographically diverse economic ties is that it will allow them to reduce their reliance on China. India opted out of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), exiting negotiations in 2019 because of its suspicion of Beijing and the country’s growing dominance in high tech.

For the struggling Tories, the proposed FTA would be the biggest of its kind since Britain left the EU and a rare “Brexit opportunity” in a year marked by supply and transport crises and broader economic turmoil, largely of the government’s own making.

India is one of the world’s largest markets for Scotch whisky, and recently surpassed China as the largest country of origin of foreign students in the UK. A UK Department of Industry and Trade study published in January estimated that a trade deal could enhance the two countries’ trade turnover, worth £23.3bn in 2019, by up to £16.7bn by 2035.

“There is a strong interest from both countries to do it for geostrategic reasons, and a strong interest from business,” said Arpita Mukherjee, a professor at the Indian Council for Research on International Economic relations. “But there are also sensitivities, and some sectors where the respective sides are sensitive to opening up to competition.”

The FTA talks were recently dealt a setback (if not a death blow) when another former UK cabinet minister of Indian origin, Suella Braverman, made remarks on Indian migrants who overstay their visas which offended Modi government officials. “The talks have continued, but the climate got poisoned because of that,” one Indian official told Trade Secrets.

Britain’s political turmoil is also probably playing a role in the timetable for the talks. While the FTA’s particulars are in the hands of bureaucratic technocrats, buy-in at the top in the form of a stable UK government will be essential to seal the deal.

Kemi Badenoch, the UK secretary of state for international trade, said on a recent visit to a Scottish distillery (part of an industry poised to profit handsomely if India lowers alcohol tariffs bilaterally) that “we’re no longer working to the Diwali deadline”.

However, she added Britain’s focus was on “the deal itself rather than the date”. Sunil Barthwal, India’s commerce secretary, said last week that talks were headed in the “right direction” even if they would not be concluded right away.

Business lobbies who want the FTA are playing down the delay. “As the trade secretary Kemi Badenoch said, ‘the deal is more important than the date’, so we think it is right that the negotiators keep working beyond Diwali to secure a comprehensive deal covering both goods and services,” said Richard McCallum, chief executive of the UK India Business Council. “Negotiators have made impressive progress in the last 10 months, with the majority of the chapters being closed, at least on a provisional basis.”

The UK side has taken comfort from the fact that Piyush Goyal, India’s commerce secretary, chose not to speak out publicly against Braverman’s remarks, suggesting New Delhi still wants the FTA as much as London does.

However, no trade deal is ever done until every detail is agreed. The proposed pact poses negotiators on both sides an unusually complex challenge, as the two economies differ widely in their respective structures. India’s is transforming rapidly, raising questions there about the costs and benefits of opening wider to the UK now. “We have so many foreign direct investment restrictions on specific sectors — retail for example — how far can we give a forward looking agreement?” said Mukherjee. “And in return, what can we ask?”

Apart from lower tariffs, both sides will need to agree on details of reducing non-tariff barriers in areas such as phytosanitary requirements. Indian dairy products are banned in the UK, for example. British businesses have complained about customs and logistics in India as one of a long list of factors hampering their operations.

The UK wants India to lift some of its barriers to international players in service industries where its professional firms compete globally, notably corporate law and financial services. It also wants any agreement to extend to investment protection — particularly sensitive terrain in India after it lost a tax battle with Vodafone in a $2bn international arbitration case.

Meanwhile, India wants as part of the FTA enhanced visa access in the UK for short-term stays by its professionals — one reason why Braverman’s remarks rankled New Delhi so much.

Taking both sides at their word that they want a deal, the more relevant issue is not whether it will happen but how deep a potential FTA will go. People close to the talks on both sides say that what is currently being discussed goes deeper than the ones India signed with the UAE and Australia’s smaller economies, which covered a more limited range of goods and services than what is now on the table. People on both sides say the direction of travel is firmly toward a deal. Multiple drivers are keeping the talks on track: a convergence of views on the need for partnerships in a changing world, Britain’s need for Brexit successes, and India’s voracious need for capital from partners other than Beijing.

“The real reason we are both doing this is because of China,” one official said.

Alan Beattie writes a Trade Secrets column for FT.com every Wednesday. Click here to read the latest, and visit ft.com/trade-secrets to see all Alan’s columns and previous newsletters too.

Charted waters

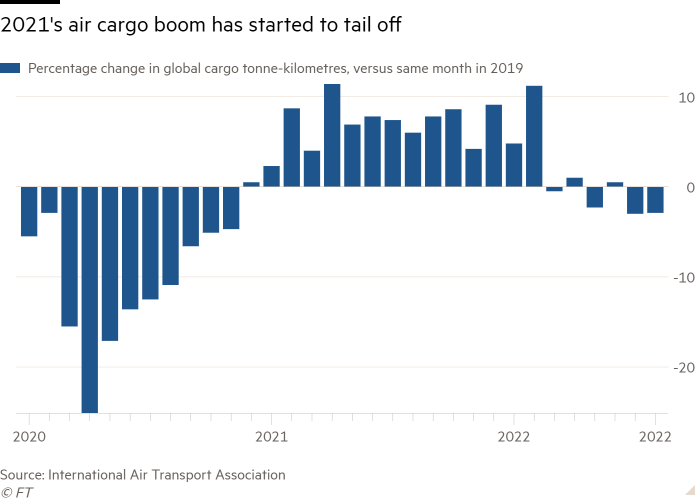

During the Covid-19 pandemic there was a surge in demand for deliveries by air, a faster but more costly option than sea transport that in the past was reserved for high-value goods.

Craig Smyth, chief of one of the world’s largest air cargo handlers, Worldwide Flight Services, is confident that this shift will continue for the long haul. Speaking with FT industry correspondent Oliver Telling, he brushed off the plunge in cargo volumes this year.

The growth of online shopping, which now accounts for a fifth of the cargo deliveries that WFS runs in some parts of the world, is what makes Smyth both “excited” and optimistic about long-term demand in his sector. “Because of ecommerce . . . there’s definitely a shift that is structural, that is permanent,” he said. (Georgina Quach).

Trade links

Energy UK, a trade body that represents companies including Centrica, EDF Energy, ScottishPower and SSE, has said the government’s revenue cap on low carbon electricity companies will have “catastrophic” effects on green investment, Natalie Thomas reports

The latest FT film looks closely at how Brexit hit the UK economy, the “conspiracy of silence” across the political spectrum, and why there has not yet been a convincing case for a Brexit dividend

The Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company is at the centre of both a tug of war between Washington and Taipei and the fiercest front in the new cold war between China and the US. Kathrin Hille in Taipei and Demetri Sevastopulo in Washington analyse what is at stake in the chips market. (Last month I wrote a Big Read exploring India’s ambition to manufacture semiconductors — which could prove extremely lucrative for the country)

Trade Secrets is edited by Georgina Quach today.

Recommended newsletters for you

Europe Express — Your essential guide to what matters in Europe today. Sign up here

Britain after Brexit — Keep up to date with the latest developments as the UK economy adjusts to life outside the EU. Sign up here