As India gears up for the general elections in just six months, expectations for cash handouts and other populist measures from the Narendra Modi-led government are increasing. Amid the discussions around fiscal loosening ahead of the elections, the chief economic advisor has indicated that the government is well within achieving its fiscal deficit targets, with pre-election populism unlikely.

Indeed, the FY23-24 budget, the last full one before the elections, focused on increasing capital expenditure to the tune of class=”webrupee”>₹10 trillion, while limiting subsidies and revenue expenditure. The central government’s budgeted capital spending, as a proportion of total expenditure, is now close to levels seen in the early 2000s — the peak investment phase for India; the same is increasing for states as well. Not only that, the ₹10 trillion central government capital spending budget is progressing faster than in the past years, with 50% of the target already spent in the first six months of the fiscal year.

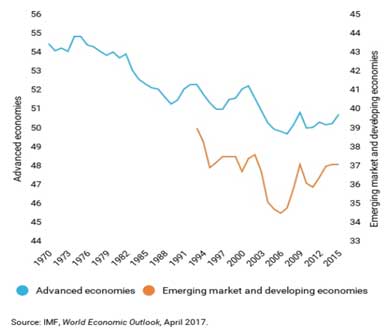

The revival in investment, after years of weakness, has been a much-discussed issue during the recovery of the economy from Covid. The share of investment-to-Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has hovered around 30% in the past three years, after slipping from the peak of 41.95% in FY07-08.

Both private and public sector investments have been slow: While private investment fell in line with slowing credit growth and balance-sheet stress over the past decade, government investment declined due to fiscal consolidation after 2013.

This decline in capacity creation has shown up in capacity utilisation across sectors. For instance, the aviation load factor was close to 90% pre-Covid and is closing in on that level again. Similarly, with investment in the power sector dropping off, installed capacity growth has weakened, and power plants are facing the highest peak loads in decades. Supply needs to now play catch up.

The need to reinvigorate investment to achieve higher GDP growth is well understood, and we think India is returning to this tried and tested playbook to achieve the government’s ambition of making India a $5 trillion economy by 2025. This is especially true in the public sector, with the government leading investment in traditional sectors such as power, roads, and railways. The government’s ambitious National Infrastructure Pipeline has 9,483 projects under its wings in various stages of planning and implementation, with a cost of approximately ₹290 trillion to be achieved by 2025. Even if the government can achieve 60% of its stated target, investment would be close to pushing India’s growth structurally above a 7%-handle from the current 6-6.5%.

However, the government has, in this term, shown restraint in loosening the purse strings too much, lest hard-earned macro stability is lost amid the various shocks buffeting the world economy. After a large push towards capex in the past three years, the government will need to slow this pace to make way for the consolidation of the fiscal deficit, which will likely lead to a reduction of such strong nominal spending on infrastructure. This means the baton has to pass to the private sector.

But where is the private sector? After a material pullback with the souring of the credit-led boom in 2016, private sector capex has languished.

After nearly a decade, cyclical and structural factors may be aligning for a rebound in private corporates’ investment. Uncertainty for the domestic economy is lower, despite the upcoming election cycle. Capacity utilisation is at high levels – close to the inflection point where private investment typically picks up.

After a painful adjustment, the twin balance sheet crisis has turned into an advantage, with the bank and corporate balance sheets materially de-levered with enough space to deploy additional financial resources for building productive capacity. NPAs of the commercial banking system in FY23 have fallen to 3.9%, almost equal to the average NPA over FY04-08 (4%), which was the period of fastest private investment growth.

In the 2000s, the domestic credit-to-GDP ratio rose from approximately 136% to approximately 182% by 2010, and this was largely led by the private sector, which also saw its debt levels rise significantly. This large increase in debt was repaid over the past decade.

At this juncture, private-sector credit growth has started picking up again, indicating that some leverage is slowly being built up. Healthy underlying debt ratios, both relative to the past and to equity, add to the conducive environment for the private sector to invest in productive capacity.

An additional advantage comes from the growing appeal of India as one of the China+1 destinations. The Indian government’s focus on raising exports and its incentives such as the Production Linked Incentives (PLIs) for goods exports should help private investment in manufacturing related sectors. Several factors have aligned to make the starting point favourable for private investment, but the challenge of sustainability of the cycle remains. The foremost among these is the financing of private investment domestically.

An increase in investment has to be accompanied by an increase in domestic savings, lest external metrics worsen. This was the case in the mid-2000s, when investment in India saw its best run and the current account deficit was also kept in check. Domestic financing for private investment may become easier as the government takes a backseat. The still volatile external environment, with elevated geopolitical risks, could further delay the private capex push.

Rahul Bajoria is MD and head of EM Asia (ex-China) Economics and Shreya Sodhani, regional economist at Barclays. The views expressed are personal

Continue reading with HT Premium Subscription

Daily E Paper I Premium Articles I Brunch E Magazine I Daily Infographics