A few months back, I did a MoneyIllusion post that discussed a fantastical airport project mentioned in an old Life magazine. The same issue (from March 18, 1946), has a few other articles worth thinking about. Here’s one example:

The phrase “iron curtain” brought back a lot of memories. It was a term one often heard back in the 1960s.

When the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, I recall being mildly surprised to learn that it had gone up as recently as 1961. I suppose that as a young person in the 1960s I thought in concrete terms, and mentally conflated the (metaphorical) “Iron Curtain” of 1946 and the (physical) Berlin Wall built in 1961. If you’ll allow me to indulge in a few meandering observations about time, I’ll eventually derive a few policy implications.

In 1989, I was 34 years old. It seemed like the Berlin Wall had been there forever, and I never expected to see it come down. I was too young to follow world affairs in 1961, and thus had no memory of the 16-year period after WWII when there was an “Iron Curtain” but East Germans were still free to travel to the West.

As one gets older, time seems to pass more rapidly. Today, the Berlin Wall has already been down for longer than it was up. My 96-year old mother probably doesn’t recall the wall as lasting as long as I perceived it to last, as she was already 35 years old when it went up. And to my daughter, it’s just a footnote in the boring history of the 1900s: Berlin Wall (1961-89). For me, it was a formative experience.

Back in 1965, I was a ten-year old boy playing WWII games, at a time when WWII seemed like ancient history. The Vietnam War was already underway, and WWII wasn’t even the previous war (recall Korea). Today, the Iraq War doesn’t seem so long ago to me. Time is subjective.

Policy problems that seem insolvable to one generation, are just a footnote to the next. I recall when there was a long struggle to contain Soviet expansionism in the third world. Then there wasn’t. This was immediately followed by worry over Japan’s increasing economic power. That concern faded just as quickly. Later there was expected to be a long struggle against Islamic terrorism, a struggle that was mostly over (in America) long before we realized that it had ended. I’m not quite sure what we worry about today. The left seems worried about right wing militias trying to overturn elections, while the right worries that woke schools will indoctrinate our children. And almost everyone worries about China and Russia.

Because of the way that we perceive time, when we are in the midst of a problem we don’t tend to perceive it as a blip in history, which will soon be replaced by another set of concerns. For this reason, there can be real benefit to foreign policies that “kick the can down the road”, if we are able to avoid outright war. Today, it seems as though places like Russia, China, Iran, North Korea, Cuba and Venezuela will never become free. But who knows what the world will look like in another 30 years.

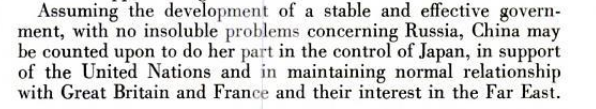

The same issue of Life magazine also has a long article by Joe Kennedy (JFK’s dad), discussing foreign policy. Some of his takes haven’t held up well:

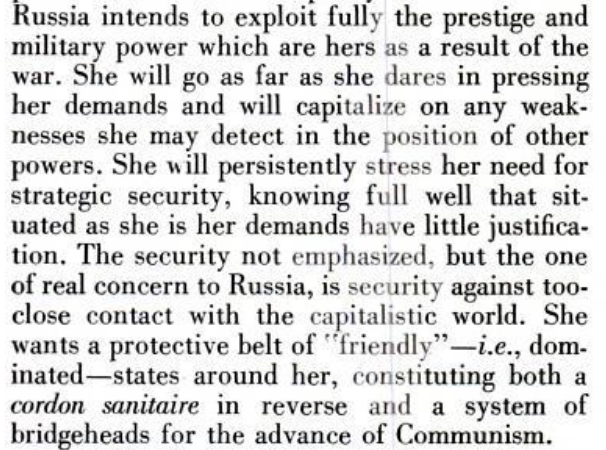

Others have held up extremely well:

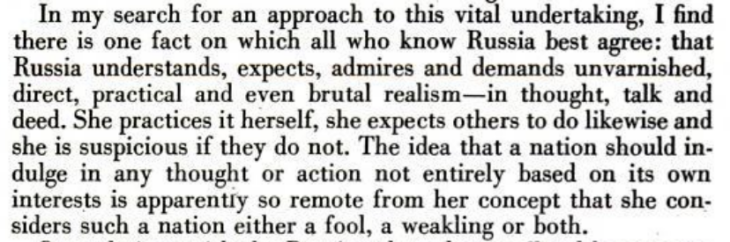

Replace “Communism” with “fascism” and that almost perfectly describes Putin’s Russia. As does this:

We avoided war with the Soviet Union through a policy of containment, and I hope that we can avoid war with Russia in a similar way. Let’s hope that at some point in the future, Kennedy’s description of Russia seems just as out of date as his 1946 comments on China.

PS. For my generation, the Berlin Wall discredited communism. Yes, America has a wall on its southern border, but (although counterproductive) it’s not there to keep people from escaping a flawed system in America. It’s to keep people from escaping to America. Some democratic countries had (misguided) policies that banned foreign travel during Covid, but these “walls” were seen as temporary. The Berlin Wall was different. Back when I was young, the Berlin Wall was seen as permanent, in much the way that the division of Korea seems permanent to the millennial generation.

When the Churchill made his speech in 1946, it was not obvious to every thinking person that the Soviet Union was an evil empire. Just a year earlier they were our ally, playing a major role in defeating Nazi Germany (and to a lesser extent Japan.) The Berlin Wall was such a perfect expression of failed tyranny that even poorly informed Americans understood the true nature of the Soviet Empire. In retrospect, 1961 was the beginning of the end for communism, the point at which it became obvious that it was failed regime.

Reading old magazines and newspapers is an interesting way of learning about history. By reading the NYT from 1929-1938, I gained a great deal of insight into the US during the Great Depression, an insight I never would have gained from history books.

PS. I originally wrote this post in January. In February, The Economist made a similar observation:

Those still feeling dour should take courage from recent experience. For all the considerable difficulties of the past decade or so, global trade as a share of GDP has only retreated a little from the peak it reached in 2008. Recent history demonstrates, moreover, that nothing in geopolitics is for ever—and trends which look inexorable come to an end. The cold war divided the world and then, suddenly, it did not. Supreme confidence in the inevitable spread of democracy was displaced by the worry that an authoritarian China would dominate the globe, which is now barely a worry at all. The stalemate between America and China will one day be old news, perhaps sooner than most currently think.

Mistakes led the world to its current uncertain state, it is true. And more mistakes will certainly be made. But the past shows only what has gone wrong, not what will. It is by remembering this that we find the wisdom to do better.