Text size

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warned Congress that the U.S. would hit its debt ceiling this coming Thursday.

Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images

It’s always fun until the bill comes due—and the bill always comes due. In fact, it’s coming due right about now.

On Friday, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warned Congress that the U.S. would hit its debt ceiling this coming Thursday, earlier than many had expected. That doesn’t mean the government will be forced to stop paying its bills then—Yellen believes that the Treasury has enough cash and other ways to raise money to last it until early June—but it does mean that an issue that was still purely theoretical has become far more pressing as the X date approaches.

You wouldn’t know it from the stock market’s reaction. The

S&P 500

was down about 0.2% at the time of the announcement Friday and finished the day up 0.4%. Maybe that makes sense. The market does have a lot on its mind, after all, from economic data to earnings to Federal Reserve speakers, all matters that seem far more pressing at the moment.

The battle against inflation is likely the most pressing—and the reason the S&P 500 finished up 2.7% this past week. The consumer price index fell to 6.5% in December, from 7.1% in November, while core CPI dipped to 5.7% from 6%. Recession fears also ratcheted down a notch on Friday, when the University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Survey came in much stronger than expected.

The two, of course, are linked. “Despite broad concerns that the economy will fall into a recession in the coming quarters, consumer attitudes are improving, mostly because it looks like the peak of inflation is now in the rearview mirror,” writes Jefferies economist Thomas Simons.

News like that—as well as very bearish positioning heading into 2023—helped the stock market ignore Yellen’s announcement. Still, there’s a good chance the debt ceiling, which currently sits around $31.4 trillion, becomes a bigger concern. In a strange quirk, Congress can approve all the spending it wants, but it also needs to approve the total amount of debt the U.S. can hold. That was once considered a nonissue. The ceiling would be reached, Congress would raise it, and everyone would go on their merry way. But that changed in 2011, when Republicans, who had regained control of Congress, threatened not to do so. It resulted in Standard & Poor’s cutting the U.S.’s credit rating on Aug. 8, causing the S&P 500 to fall 6.6%.

The stakes might be higher this time. Not only is Congress divided, with the Democrats controlling the Senate and Republicans the House, notes Michael Gapen, chief U.S. economist at Bank of America, but the deal Kevin McCarthy made to become Speaker of the House ceded enough power to a small group of legislators to make the issue even more difficult.

The repercussions could also be more severe, particularly if the U.S. is forced to miss payments on its debt or halt spending, perhaps even on Social Security. These would all count as defaults and result in more credit-rating downgrades—and more economic pain. “The bottom line is that passing the X date could bring substantial economic pain,” Gapen writes. “It is not part of our baseline outlook at present, but we think fiscal brinkmanship has returned.”

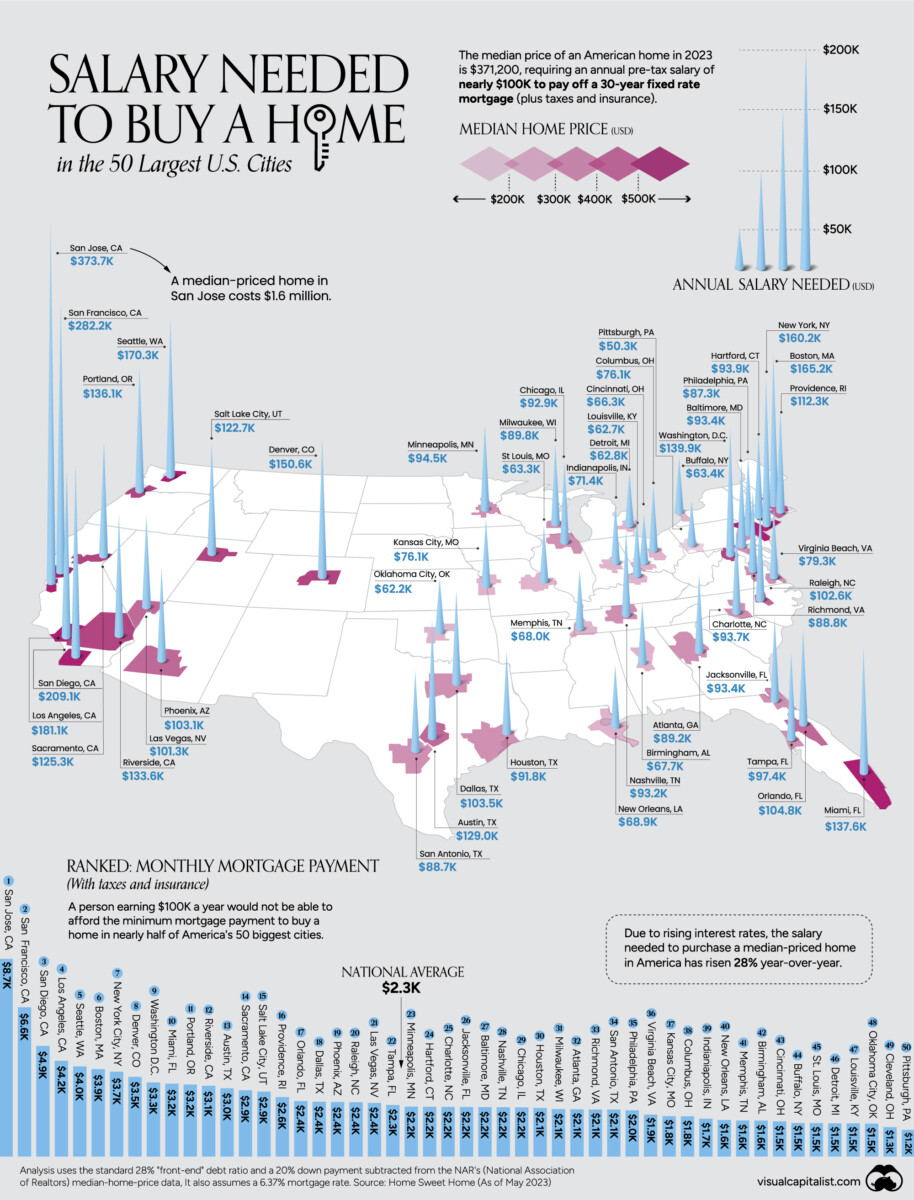

That’s unfortunate. The national debt is a real problem, one that deserves serious consideration, not the gamesmanship of a debt-ceiling standoff. President Joe Biden’s 2023 budget calls for a $1.2 trillion deficit, a shortfall that is far smaller than 2020’s record Covid-induced $3.1 trillion, but still larger than 2019’s $984 billion. The national debt is now 120% of gross domestic product, up from 106% in 2019. Those deficits haven’t yet been a problem for the U.S., but markets have started losing patience with other countries. The United Kingdom, for example, was forced to pull back on a fiscal-spending plan after the bond market rebelled.

Running large deficits will also make the fight against inflation more painful, argues Société Générale’s Solomon Tadesse. Less deficit spending would make it easier for the Fed to do its job. Without it, it will fall into a cycle of overtightening and balance-sheet reduction, followed by rate cuts and more quantitative easing, which will only spur more inflation and force the “vicious circle” to start again, he says: “For markets, brute-force monetary tightening without concomitant fiscal discipline that significantly slashes budget deficits and debt financing may only provide a temporary reprieve, if any at all.”

The national debt also makes it more difficult for the Fed to do its job. Barry Bannister, chief equity strategist at Stifel, notes that higher yields would make paying interest on the national debt untenable, forcing the Fed ultimately to cap yields, similar to what it did during and after World War II.

This yield-curve control would keep the debt manageable, but it would be bad news for stocks because it would ultimately lead to higher inflation and lower valuations. Bannister expects the S&P 500’s price/earnings ratio to be halved from its 2021 peak by 2030, even as earnings per share double. That would leave the S&P about even with its 2021 level at the end of the decade.

That, of course, says nothing about the current rally, which he thinks has further to run in what he calls a “rangebound secular bear market.”

Enjoy it while it lasts.

Write to Ben Levisohn at [email protected]