Many nations have undertaken massive reforms to their public pension programs over the previous twenty years, and extra appear prone to comply with swimsuit within the close to future. A typical theme of those reforms has been to induce employees to retire later (e.g. Gruber and Clever 1999, OECD 2019, Barr and Diamond 2009) with the intention to restore fiscal sustainability in gentle of ageing populations. That’s, along with lowering the generosity of public pensions typically, reforms in lots of nations have launched or strengthened incentives favouring longer working lives. Such incentives have fascinating fiscal results – employees who retire later pay extra tax – however their total welfare results are nonetheless poorly understood.

In a current paper (Kolsrud et al. 2021), we suggest a framework to analyse the welfare results of pension reforms that incentivise later retirement. The coverage query we examine basically considerations the optimum steepness of the pension advantages profile as a operate of the retirement age. How quickly ought to pension advantages rise for employees who retire later in life? Our evaluation enriches the present literature, which, in distinction, primarily revolves round questions of the general generosity of pensions, whether or not they’re funded or pay-as-you-go, and the response of retirement timing to pension incentives.

The price of a steeper profile

A key amount to guage the price of a steeper profit profile is the worth that people retiring at totally different factors in life connect to the pension profit as a method of smoothing consumption when retired. If individuals who retire earlier worth pension advantages greater than these retiring later do, then incentivising later retirements through the pension system entails welfare prices. Particularly, these reforms redistribute assets away from individuals who worth them comparatively extra (early retirees) and towards those that worth the advantages comparatively much less (late retirees). In our paper, we present that the scale of this welfare price relies on the marginal utility of consumption of employees retiring at totally different ages. If, all else equal, early retirees have a lot larger marginal utility of consumption than late retirees, as an illustration, this implies {that a} steeper profile has a big welfare price.

However do early retirees even have larger marginal utilities of consumption than late retirees, and in that case, simply how a lot larger? To make clear this query, we use administrative information from Sweden and registry-based measures of family consumption (Kolsrud et al. 2020). Mapping consumption information to marginal utilities requires some assumptions, so we make use of quite a lot of methods of consumption and complement consumption information with information on wealth, well being, and life expectancy.

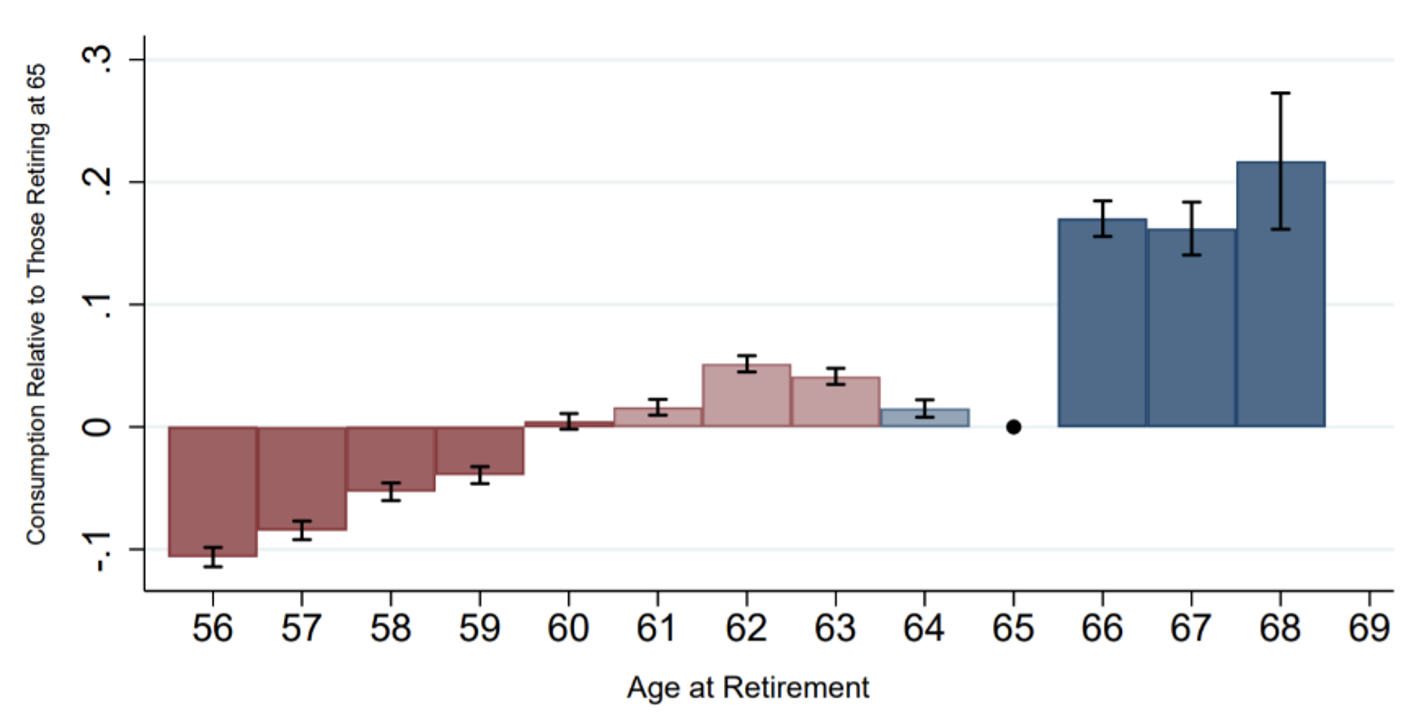

In accordance with financial concept, one key determinant of the marginal utility of consumption is the extent of consumption itself: the upper the latter, the decrease the previous. So, we begin by merely inspecting how total consumption post-retirement varies throughout employees who retire at totally different ages. Determine 1 exhibits how consumption at age 68 varies with retirement ages, evaluating every retirement age group to these retiring at 65 (which we contemplate as a benchmark for a standard retirement age). The general gradient of consumption with respect to the retirement age is steep, with late retirees having fun with over 20% extra consumption than untimely retirees. This means that rewarding later retirement by giving later retirees extra beneficiant pensions redistributes from low-consumption to high-consumption households. Notably, whereas the general consumption gradient between retirees at ages 55 to 70 is massive and optimistic, we additionally doc a notable non-monotonicity amongst these retiring at ages 60 to 65. People retiring between 60 and 63 years have comparable or larger consumption on common in comparison with these retiring close to the traditional retirement age of 65. We verify the identical total patterns when finding out surveyed consumption in different European nations and the US.

Determine 1 Consumption stage by retirement age

Notes: The determine stories estimates of our comparability of consumption ranges throughout all retirement ages. People who retire at 65 are the reference class. On this specification, solely yr and age mounted results are included.

The function of socioeconomic background

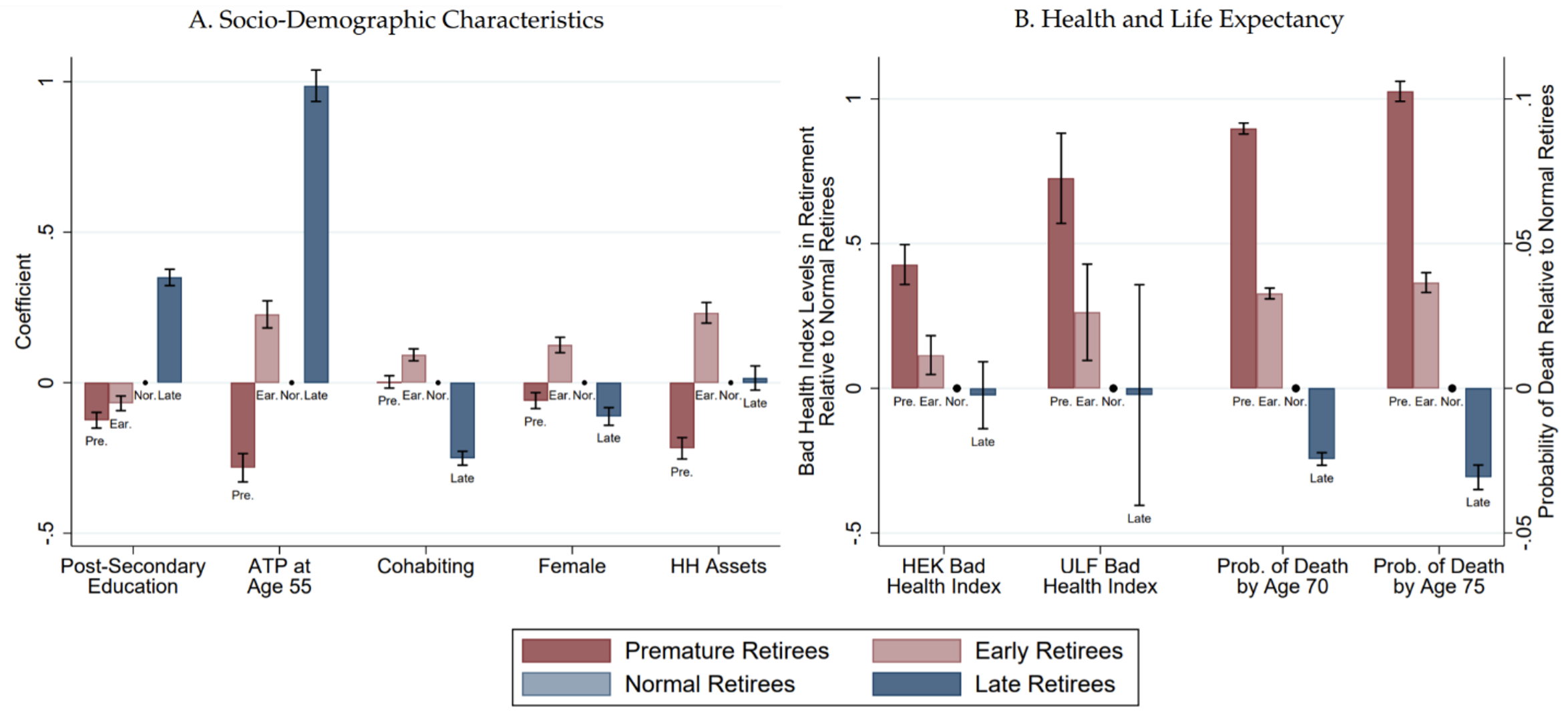

Naturally, the extent of consumption may not be the only real determinant of marginal utility. Different components could matter, together with well being and life expectancy which instantly have an effect on the redistributive weights one desires to assign to totally different retirees as nicely. We analyse wealthy information on the traits of retirees at varied ages to assist us perceive how these components would possibly change our analysis of pension reforms. Determine 2 illustrates how people who retire early/late differ of their observable traits, in comparison with these retiring across the regular retirement age of 65. The primary panel considers socio-demographic traits and the second panel considers well being and life expectancy. The outcomes broadly reinforce our discovering {that a} steeper pension profit profile redistributes from these with a excessive worth of pension advantages (earlier retirees) to these with a smaller worth (later retirees). Specifically, later retirees are likely to have extra training, extra productive careers and extra monetary assets than these retiring very early. We additionally doc, in Determine 2B, that well being and life expectancy are considerably worse for these retiring early. Therefore, steeper incentives take away assets from people who find themselves not solely much less resourceful, but additionally endure from worse well being.

Determine 2 additionally sheds gentle on the drivers underlying the non-monotonicity within the consumption gradient. These retiring between ages 61 and 63, the place the non-monotonicity seems in Determine 1, usually tend to be cohabiting and/or feminine. They’ve larger family property and are usually in households the place one other member of the family earns vital earnings. The non-monotone sample can also be decreased when controlling for family composition. Therefore, inside this vary of retirement ages, from 61 to 65, incentivising later retirement is arguably more cost effective than at different ages.

Determine 2 Heterogeneity and choice into retirement ages

Notes: The determine paperwork patterns of heterogeneity throughout retirement age teams. We outline untimely retirees by these retiring between 56 and 60, early retirees by these retiring between 61 and 63, regular retirees by these retiring at 64-65 and late retirees by these retiring at 66-69. Panel A shows estimates from a multinomial logit prediction mannequin for retiring in one of many 4 totally different age teams. We report for every regressor the estimated marginal results predicted on the imply on the relative likelihood to pick into every of the teams, utilizing regular retirees because the reference class. Panel B explores choice on well being and life expectancy. We use two indices for unhealthy well being (i.e. standardised principal elements extracted from all well being outcomes within the HEK and ULF surveys) and two measures of “life expectancy” (dummies for being lifeless by age 70 or by age 75).

Completely different traits in consumption

Financial concept offers us with a number of methods to be taught concerning the marginal utility of consumption from information on consumption. One other strategy we soak up our paper is to look at how the drop in consumption at retirement varies throughout employees retiring at totally different ages. This strategy depends on weaker assumptions concerning the relationship between retirement age and marginal utility than the consumption ranges strategy. It additionally isolates the ‘social insurance coverage’ worth of pensions towards work longevity threat, i.e. the danger involving when a person might want to retire for e.g. well being causes (Diamond and Mirrlees 1978, 1982, 1986), whereas disregarding redistributive results throughout people. The drop in consumption at retirement has been broadly studied and debated (e.g. Bernheim et al. 2001, Aguiar and Hurst 2005, Battistin et al. 2009, Stephens and Toohey 2018), however with out contemplating how this drop varies by the retirement age, which is vital for our query concerning the welfare results of incentivising later retirement.

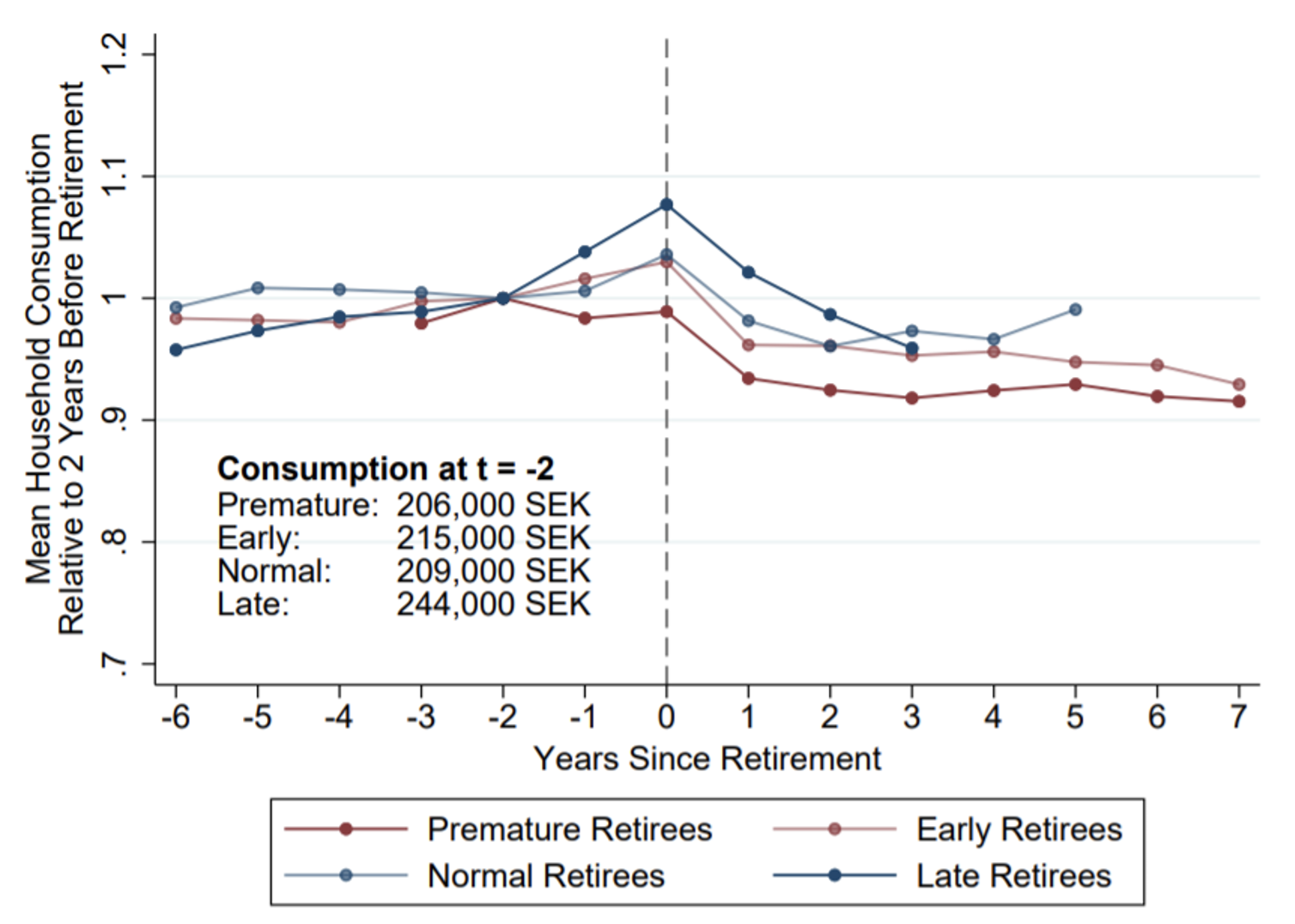

The principle consequence from this evaluation is displayed in Determine 3, the place we plot the imply family consumption relative to 2 years earlier than retirement. We estimate that the consumption drop from two years earlier than retirement to 2 to 5 years after retirement is way bigger for very early retirees in comparison with later retirees. This reality is per a considerable distinction within the marginal worth of pension advantages to the previous versus the latter teams. Within the paper, we use information on the dynamics of well being to indicate that a lot of this seems to be defined by well being shocks incurred by untimely retirees. We additionally study how marginal propensities to eat out of wealth shocks differ throughout retirement age teams (Landais and Spinnewijn 2021). These outcomes verify our total discovering that incentivising later retirement entails a considerable price as a result of it takes assets away when the marginal utility of consumption is excessive and offers extra assets when the marginal utility of consumption is low.

Determine 3 Variations in consumption drops

Notes: The determine paperwork consumption dynamics round retirement. It plots common residualised (with respect to cohort mounted results, age mounted results, social insurance coverage contributions at age 55 and family construction) consumption as a operate of time to retirement, individually for untimely, early, regular and late retirees. The group definition is identical as in Determine 2. The graph scales the residual consumption of every group by its stage two years previous to retirement (this stage can also be reported on the graph). Due to the yr and cohort protection of our consumption and retirement pension information, the earliest we are able to observe consumption amongst all untimely retirees is three years previous to retirement. And the newest we are able to observe consumption amongst all of the late retirees is three years after retirement. This explains the differential protection of the residualised consumption sequence.

Conclusions

Incentivising later retirement is a typical theme of pension reform in lots of nations. Most discussions of those reforms, in tutorial work or public debate, deal with the truth that strengthening incentives to retire later might help restore fiscal sustainability of the pensions system. Nonetheless, we discover that incentivising later retirement entails doubtlessly pivotable welfare prices as nicely by reallocating public pension advantages from comparatively needy to comparatively well-off people. The broadly employed framework for fascinated about optimum provision social insurance coverage (Bailey 1978, Chetty 2006) highlights that introducing incentives which have fascinating fiscal properties can usually entail these kind of prices. By adopting this framework to pensions and exhibiting that the redistributive prices look like substantial, we spotlight that prior literature on pension reforms has primarily centered on only one aspect of a tough trade-off: between offering beneficiant pensions to these most in want, who are likely to retire early, and sustaining fiscal sustainability. Nonetheless, we additionally discover there are some ranges of retirement ages – between ages 60 and 65 – the place incentivising later retirement is probably going more cost effective. Right here lies a possibility to offer stronger incentives to work longer and easy consumption between households.

The general framework we offer can be utilized to check different sorts of pension reforms as nicely, together with modifications to the relation between pension advantages and profession size, modifications to the minimal pension profit and/or modifications to incapacity insurance coverage for old-age employees. Future work might study different sorts of pension reforms which may present incentives that promote fiscal sustainability with out incurring the massive welfare prices of broad incentives for later retirement.

References

Aguiar, M and E Hurst (2005a), “Consumption versus expenditure”, Journal of Political Financial system 113(5): 919–948.

Baily, M N (1978), “Some elements of optimum unemployment insurance coverage”, Journal of Public Economics 10(3): 379–402.

Barr, N and P Diamond (2009), “Reforming pensions: Rules, analytical errors and coverage instructions”, Worldwide Social Safety Assessment 62(2):5–29.

Battistin, E, A Brugiavini, E Rettore and G Weber (2009), “The retirement consumption puzzle: Proof from a regression discontinuity strategy”, The American Financial Assessment 99(5): 2209–2226.

Bernheim, B D, J Skinner and S Weinberg (2001), “What accounts for the variation in retirement wealth amongst US households?”, The American Financial Assessment 91(4):832–857

Chetty, R (2006), “A normal components for the optimum stage of social insurance coverage”, Journal of Public Economics 90(10-11): 1879–1901.

Diamond, P and J Mirrlees (1978), “A mannequin of social insurance coverage with variable retirement”, Journal of Public Economics 10(3):295–336.

Diamond, P and J Mirrlees (1982), “Social insurance coverage with variable retirement and personal saving”, MIT working papers 296.

Diamond, P and J Mirrlees (1986), “Payroll-tax financed social safety with variable retirement”, Scandinavian Journal of Economics 88:25–30.

Gruber, J and D A Clever (1999), “Introduction to ‘Social Safety and Retirement across the World’”, In Gruber, J and D A Clever (editors), Social Safety and Retirement across the World, Worldwide Social Safety, College of Chicago Press.

Kolsrud, J, C Landais and J Spinnewijn (2020), “The worth of registry information for consumption evaluation: An utility to well being shocks”, Journal of Public Economics 189: 1040–1088.

Kolsrud, J, C Landais, D Reck and J Spinnewijn (2021), “Retirement Consumption and Pension Design”, CEPR Dialogue Paper No. 16420.

Landais, C and J Spinnewijn (2021), “The worth of unemployment insurance coverage”, Assessment of Financial Research 88(6): 3041–3085.

OECD (2019), Pensions at a Look 2019: OECD and G20 indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Stephens, M and D Toohey (2018), “Modifications in nutrient consumption at retirement”, NBER Working Paper No. w24621.