India is adopting automation at a global pace. According to the second edition of Deloitte’s State of AI in India report in November 2022, close to 90% of Indian enterprises are considering boosting their investments in Artificial Intelligence (AI). This thrust is highest in communication, over-the-top (OTT) programming and gaming, technology, and financial services. According to the International Data Corporation (IDC), India’s AI market was valued at $3 billion in 2020, and is expected to grow at the second fastest rate of 20% among major economies over the next five years, behind only China. The National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence (NSAI) highlights that AI is expected to boost India’s annual growth rate by 1.3% by 2035.

Automation is critical for improving operational efficiency, quality and consistency, and reducing time, effort and cost. The adoption of automation, especially in the current inflationary business environment, is inevitable. But it is important to note that this phenomenon has its downsides.

A recent paper by Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Daron Acemoglu and Boston University professor Pascual Restrepo published in Econometrica showed phenomenal widening of wage inequality in the United States (US) over the last three decades. The authors were able to show that a major contributor to this phenomenon was the rise of automation and robotics (and not international trade and the decline of trade unionism, which were traditionally regarded as the main culprits).

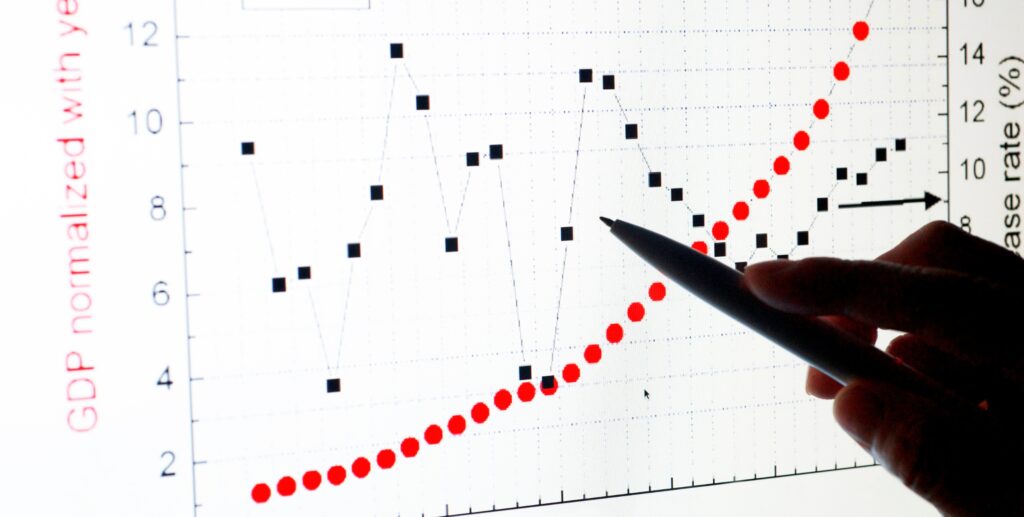

Using industry-level data from 1987 to 2016, Acemoglu and Restrepo showed that in the last three decades, automation caused wages of unskilled and semi-skilled workers (or blue-collar workers), but not of skilled workers, to fall substantially. This, they argued, happened because the unskilled and semi-skilled workers were most vulnerable to losing employment and income as the kind of jobs they were involved in could easily be automated. As a result, they competed for fewer jobs with other blue-collar workers, which pushed down wages. Meanwhile, better-skilled and educated workers — whose jobs couldn’t be easily automated — saw higher wages. These trends, naturally, resulted in an increase in wage inequality in the US.

This is extremely concerning for a country such as India, where automation is gaining tremendous momentum and income inequalities are already high. Additionally, a majority of the workforce in India consists of unskilled and semi-skilled workers (according to the Human Development Report 2020, four out of five workers in India are either unskilled or semi-skilled). As it happened in the US, if the rise of automation drives down the wages of these workers, an already unequal India is likely to see a further increase in economic inequality. This could not only lead to economic and social unrest, but also hurt economic growth, hampering India’s aspirations of becoming a $10 trillion economy by 2030. It might also, in a society with deep cleavages, stoke instability.

Of course, there is no running away from automation; AI and robotics are here to stay. However, the government can take several steps to combat the threats. It has to focus on an expansion of education and upskilling workers. For instance, machinists and welders might see a reduction in their wages as their jobs can be automated. However, if they can get the opportunity to become designers, then they are unlikely to see a wage reduction because the tasks that designers perform cannot be easily automated. Skill development centres and programmes, therefore, will be key.

Second, there are several schemes by which the government encourages new entrepreneurs and businesses (such as Startup India). The authorities must ensure that the majority of the businesses that are selected under such schemes aren’t fully or largely automated. Finally, the much talked about universal basic income scheme might be a way through which the government could support those adversely affected by automation. Whether such a proposal is fiscally feasible is for the government to consider.

In the 19th century Gothic novel Frankenstein, Mary Shelley narrated the story of a student who created an artificial man from pieces of corpses and brought it to life, only to see the creation wreak havoc. Automation, to an extent, seems like an updated version of that artificial man. If we don’t want our creation to hinder economic growth and social stability, we must take steps without delay.

Punarjit Roychowdhury is assistant professor, department of economics, Shiv Nadar University

The views expressed are personal