This article is an on-site version of our Trade Secrets newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Monday

Welcome to Trade Secrets. The crisis in supply networks, or at least the container-shipping bit of them, is receding so quickly the deprivation will surely soon be remembered with a kind of accelerated nostalgia, a just-in-time version of those people who lived through the Great Depression and never shut up about it. Clogged-up ports, fully-laden container ships twiddling their thumbs out at sea, the word “fragility” made compulsory in all discussions of globalisation in English-language publications worldwide, it’s all fading into bittersweet memories. Today I ask whether we’ve grabbed the chance to spruce up logistics infrastructure and increase capacity for the future. Charted waters looks at the impact of the tumbling dollar.

Container decongestion

As I argued recently, it looks like great news that over the past few months the congestion in container traffic has been clearing like a bunged-up sinus dosed with penicillin. Delivery times, freight rates, wait times — they’ve all been dropping, though some shortages of semiconductors and other critical goods persist.

Unfortunately, it’s all because of bad times for the global economy and hence the goods trade, which tends to move with world gross domestic product, but with bigger swings. Those of us who reckoned the snarl-ups were more about an extraordinary surge in demand for consumer durables after the Covid-19 lockdowns lifted (more e-bikes, fewer Netflix subs), rather than deep-seated structural problems, are doing a qualified victory dance.

I say qualified because when consumer demand comes out of the cyclical downturn, if there’s another surge in durables consumption the ports might conceivably get clogged up again. So, have governments and the freight industry done anything to prevent this? Are the connections between container terminals and land transport smoother, the management of container flow greatly improved?

I asked two proper experts: Ryan Petersen, chief executive of the freight forwarder and logistics company Flexport, one of the sharpest industry observers during the crisis, and John Butler, president and CEO of the World Shipping Council, which represents the world’s container shipping lines.

The answer: nope. Petersen said: “We haven’t learned anything. We’d like to think we’ve started to run things more efficiently and solve our infrastructure bottlenecks so we can handle an increase in demand, but actually no. Demand has subsided, and that’s it.”

Supply chain managers worked marvels to try to keep things moving, shifting container traffic from one port to another or shuffling cargo between aircraft and trucks. But they’re working within a largely unchanged infrastructure.

Petersen is particularly critical of the US west coast ports, Long Beach and Los Angeles, which together handle about a third of the US’s container trade. Flexport itself has pioneered a mobile app that allows truckers to connect quickly with the next available container. But the ports’ wider problems — size, technology and poor connection with road and rail — persist.

The port management tried a couple of quick fixes, but they didn’t achieve much. The labour unions, after coaxing from US president Joe Biden, agreed to run a 24-hour shift at Los Angeles. But only a couple of consignments showed up during the night.

Butler agrees with Petersen that there’s been little structural improvement. “The inland destinations, the warehouses and distribution centres typically don’t operate 24/7. It does no good to go to the port and pick up the box and then go sit outside of the warehouse until the sun comes up.”

So why wasn’t more capacity built? For port and landside infrastructure, Petersen says: “If you commit the money now, by the time you break ground it’ll be a couple of years. Probably by the time you actually finish it, it’ll be maybe even a decade.” California, given its desire to protect its coastline, is just about the least construction-friendly US state.

Certainly a lot of container ships are being built, with order books at record levels. But that’s pretty typical of the demand cycle, and in fact there’s a high probability of a glut a year or two from now.

Butler says: “Nothing is static in this industry, but by and large when you take out the disruptions of the nature that we saw during Covid I think you’re going to see a market that’s much more like what we had before.”

Meanwhile, some authorities are haring off in a different direction looking for someone to blame. The European Commission is investigating whether the undoubted concentration in the shipping industry and established practices such as “vessel-sharing”, where a ship is owned or managed by multiple carrier companies, are anti-competitive.

For Butler, this is just scapegoating: “There’s obviously a lot of political angst around the supply chain disruptions that occurred during Covid, and that tends to manifest itself in various entities essentially taking any opportunity they can to express their displeasure.” In any case, it’s going to be increasingly hard to make a case about cabals of shipping lines driving up prices if there’s excess capacity and freight rates continue to tank.

So that’s the story about supply network snarl-ups. They’re over for the foreseeable future, it was basically about consumer demand, nothing’s been done to improve the infrastructure and it’s not clear that will be needed anyway. A happy Thanksgiving this week to those who celebrate it.

As well as this newsletter, I write a Trade Secrets column for FT.com every Thursday. Click here to read the latest, and visit ft.com/trade-secrets to see all my columns and previous newsletters too.

Charted waters

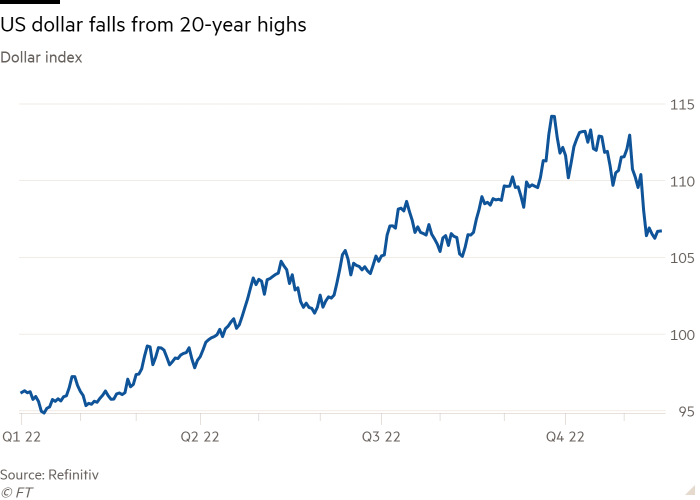

The US dollar is down. Is that good news for the global economy? The strong greenback was contributing to inflationary pressure in smaller countries and adds to debt sustainability problems for companies and nations that had previously borrowed heavily in the American currency. The strong dollar has also been a $10bn problem for US companies because of the impact it has on foreign sales revenue.

There may now be fewer Americans booking holidays to Europe because of the added expense of a less generous exchange rate. Other national governments will be feeling some relief about their recent exposure. As the FT’s chief economics commentator Martin Wolf recently noted, the US dollar has been strong because the world economy has been in trouble. It is only then, when the economic tide recedes, do we discover who has been swimming naked. (Jonathan Moules)

Trade links

Really terrific work by a star line-up of FT colleagues about how European companies are being lured by cheaper energy costs and federal dollars to move to the US, and the resulting angst in Brussels, Paris and Berlin.

The dollar has fallen rapidly over the past two weeks as expectations of US rate rises ease, which will come as a relief to those middle-income countries laden with dollar-denominated debt, and in fact most of the world in general.

Stuart Lau from Politico argues that Xi Jinping has been trying to defuse EU combativeness over trade by playing member states off against each other and the commission. (Lots of countries try this but you’ve got to have a pretty big economy to succeed.)

The American Prospect (disapprovingly, given its leftish editorial stance) says that US companies are still heavily involved in China despite all the talk of decoupling.

Trade Secrets is edited by Jonathan Moules

Recommended newsletters for you

Europe Express — Your essential guide to what matters in Europe today. Sign up here

Britain after Brexit — Keep up to date with the latest developments as the UK economy adjusts to life outside the EU. Sign up here