Writing amid a raging war in 1919, in the immediate aftermath of a devastating pandemic, Irish poet William Butler Yeats described a world in which “things fall apart”, and “the ceremony of innocence is drowned”. Yeats’ poem, The Second Coming resonates a century later as the world struggles to cope with an unending war, just after it braved a pandemic.

The innocent idea that we can all depend on and prosper from unfettered and uninterrupted global supply chains finds few takers today. Globalisation is not dead yet. But the forces of de-globalisation are gaining strength, finding powerful political patrons across the world. Old Statist ideas, long discarded, are making a comeback.

Industrial policy is one such idea. The idea that the State should determine how, where, and what an economy should produce has a long and chequered history. It is enjoying a renaissance now. Even before the war and the pandemic, some countries had begun flirting with the idea. Now, it has turned into a serious affair, with countries ranging from South Korea to the United States (US) using public funds to build domestic supply chains of semiconductor chips and electric vehicles.

Four key policy imperatives have led to this renaissance. The first is the realisation that a country’s technological prowess will increasingly determine its competitive edge in global markets. Since technological breakthroughs often demand extraordinary funding and risk-bearing capacity, the State is expected to drive such investments.

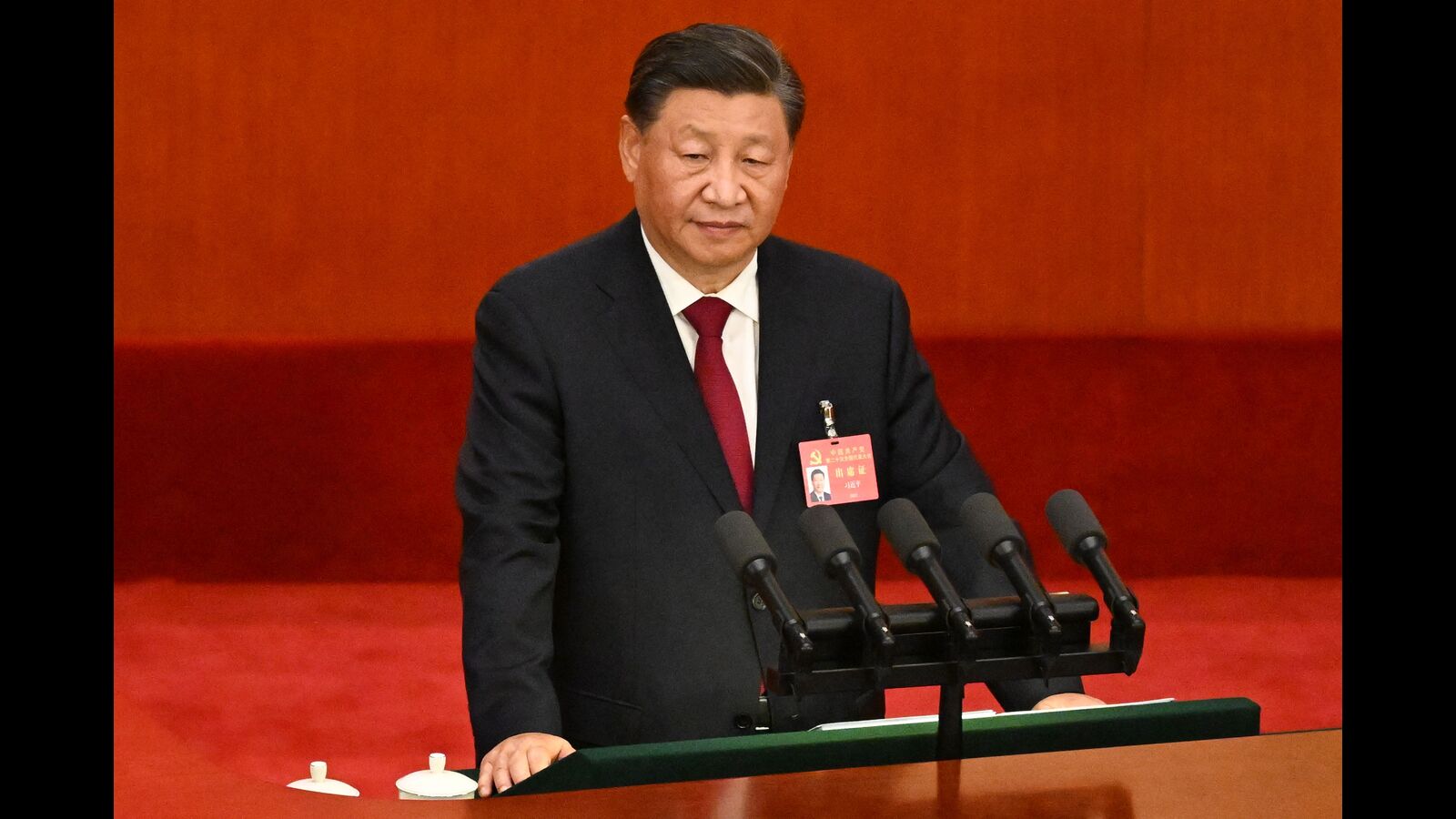

The second imperative is the need to counter the threat from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The CCP’s deep links to Chinese technology firms and its hold on industrial supply chains have raised concerns in a conflict-prone world. The fear that the CCP may weaponise China’s economic and technological prowess has led other countries to try and diversify their supply chains.

The third imperative is the green agenda. Climate-conscious citizens are forcing politicians to take credible steps to combat global warming. Policymakers realise that the State has a role to play in nudging firms to invest in green technologies since market forces can often fail to nudge them in that direction.

Finally, the imperative to quell discontent against growing inequalities has forced many policymakers to prioritise local jobs. Getting companies to “onshore” jobs has now become a key policy priority in many parts of the world. Policymakers, therefore, want a say in how domestic firms arrange their supply chains.

Industrial policy had its heyday in the middle of the 20th century, when newly decolonised countries embraced a State-led economic model to jumpstart growth and bring down poverty. In much of the developing world, including India, a sound industrial plan was seen as a prerequisite to growth and development. Just as semiconductors have acquired strategic status in today’s digitised world, heavy industry was seen as a strategic sector when India won independence, finding pride of place in the Nehruvian plans, as this column has pointed out earlier (see Ambekar, Nehru, and Atmanirbhar Bharat, April 5).

The record of Industrial Policy 1.0 was decidedly mixed. In Japan and East Asia, such policies were a resounding success. In Latin America, they were remarkably ineffective. India had a middling experience. It missed the exhilarating growth ride of the Asian tigers but managed to escape LatAm-style industrial decay and debt trap. The World Bank, which actively encouraged industrial planning in the 1950s, did a somersault in the 1980s, arguing that industrial planning failed to raise productivity, and only led to corruption, cronyism, and industrial stasis.

Industrial Policy 2.0 has so far avoided the excesses of Industrial Policy 1.0. The State is no longer in the driver’s seat as earlier, but is more of a back-seat driver. It is providing subsidies and incentives to sectors that it considers strategic or economically important. Most governments are no longer setting up new State-owned enterprises. Learning from the past, many countries, including India, have adopted a carrot and stick approach to industrial planning. For instance, in India’s production-linked incentive scheme, State support is conditional on meeting predefined production targets.

Yet, Industrial Policy 2.0 is not without its risks. It could lead to cronyism, helping entrenched conglomerates set up new lines of businesses. By fragmenting supply chains, it could end up raising inefficiencies and costs across the world, keeping inflation elevated for a long time to come. If State subsidies are accompanied with tariff protection, inefficiencies may be even higher. The biggest risk is that governments end up creating non-competitive firms that go bust when State support dries up.

As in the case of its earlier avatar, Industrial Policy 2.0 is likely to perform differently in different parts of the world. Countries with open, tolerant, and responsive governments will find it easier to navigate the uncertain path ahead since they will be able to learn from feedback and take corrective steps faster. To make industrial policy work, policymakers will have “to cross the river by feeling the stones”, as a reformist Chinese leader once advised.

Pramit Bhattacharya is a Chennai-based journalist The views expressed are personal