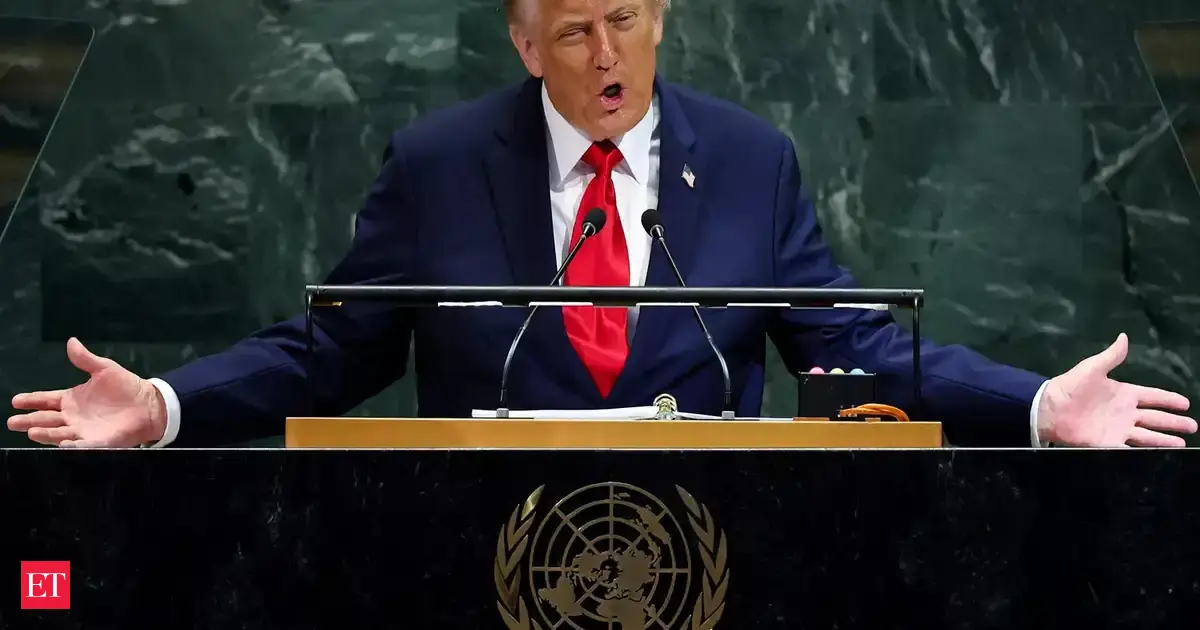

© Reuters. A woman holds up a photo of her missing relative during a protest in Kilinochchi, Northern Province, Sri Lanka, August 12, 2022. REUTERS/Joseph Campbell

2/7

(This Oct. 26 story has been corrected to drop the reference to Tamils in the headline and to make clear in paragraph 15 that both brothers were younger)

By JEEVAN RAVINDRAN

KILINOCHCHI (Reuters) – Arumuga Lakshmi, tormented by questions about the fate of her two children, missing for years, marched through a town in northern Sri Lanka with a group of women, many holding up photographs, black flags and burning torches.

During a brutal 26-year civil war between the Sri Lankan government and a militant group, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), Lakshmi’s daughter Ranjinithervy went missing in 2004, followed three years later by her son Sivakumar.

“I just want to see my son’s face,” said Lakshmi, as she wiped away tears, adding that she did not know if the two, aged 16 and 20 when they disappeared, were dead or alive.

Thousands of people, mostly Tamils, went missing during

the civil war in what were known as “enforced disappearances”.

Few, if any, have been accounted for, and government officials have offered varying details of what happened to them, with many facts still unknown, despite investigative efforts.

The instances of enforced disappearances in Sri Lanka rank among the world’s highest, with human rights group Amnesty International estimating them to number between 60,000 and 100,000 since the late 1980s.

But the government’s Office on Missing Persons (OMP), set up in 2017, said it had received just 14,965 civilian reports of disappearances from 1981 onwards.

Years after the war ended in 2009, families such as Lakshmi’s, and the hundreds of women who marched with her in the former LTTE stronghold of Kilinochchi in August, still seek their missing relatives – and answers.

Pressure is growing for the government to act.

In a report on Oct. 4, the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights said the Office, and other steps taken by the government, had fallen short of the “tangible results expected by victims and other stakeholders”.

Sri Lanka says it remains committed to pursuing tangible progress on human rights through domestic institutions.

‘JUST CAN’T BEAR THE PAIN’

Government employee Valantina Daniel said her 66-year-old injured mother disappeared during the war’s final phase.

On May 17, 2009, a day before the government declared victory, Daniel handed her mother to authorities, believing that she would be taken to hospital, but has had no word of her since.

“I developed this sense of hatred and so I tried to kill myself,” said Daniel, 51. “I’ve tried many times. I just can’t bear the pain of this separation.”

Daniel, one of whose younger brothers also disappeared in 1999, while another was killed in a shelling attack that decade, wrote to the authorities about her mother’s case, which they acknowledged in 2011.

Mahesh Katundala, chairman of the Office on Missing Persons, defended the institution against criticism that it was not doing enough.

He rebutted claims that those who surrendered went missing, saying there was no evidence, and added that the majority of those who disappeared had been abducted by the LTTE or factions opposed to it.

The Office had uncovered about 50 cases of people reported missing who were living abroad, he said.

Denying claims of a genocide of Tamil civilians during the war’s final offensive in Mullivaikkal, he said the army had instead rescued 60,000 civilians.

Among its functions, the Office issues certificates of death or of absence only when they are requested, Katundala said, while compensation amounts to 200,000 rupees ($550).

However the U.N. rights agency, among others, has faulted its efforts.

“It has not been able to trace a single disappeared person or clarify the fate of the disappeared in meaningful ways, and its current purpose is to expedite the closure of files,” the body said in the October report.

An OMP spokesperson said the fuel shortages crippling the Indian Ocean island during its worst economic crisis in more than seven decades make it impossible to meet a target of 5,000 interviews by year-end.

For Daniel, the crisis pales besides the hardships of 2009, when she went from village to village with no food and just the clothes she wore, for fear of a shelling attack.

“Finding our relatives will never, ever happen,” Daniel said, accusing the government of inaction. “Even now I’m living with so much pain.”