Why has earnings inequality been growing? Proof from an growing variety of nations signifies that the place folks work is of key significance (Card et al. 2013, 2016, Marin 2016, Berlingieri et al. 2017, Music et al. 2019, Mion et al. 2020). Some employers pay greater than others, and these pay differentials have widened in current a long time. An vital query is why employer-driven inequality has been rising over time.

In a brand new paper, we doc an vital determinant of how a lot an employer pays: the {industry} (Haltiwanger et al. 2022). An employer’s {industry} is decided by its manufacturing processes or its merchandise. Pay differentials throughout industries are massive and have widened over time, resulting in will increase in labour earnings inequality. For instance, eating places are typically low-paying employers. Our knowledge point out that in current a long time within the US, about one-tenth of the rise in labour earnings inequality may be attributed to eating places using extra folks and paying them much less.

We use matched employer-employee knowledge for 18 US states to review labour earnings inequality (hereafter, merely ‘inequality’; notice that this excludes self-employment and capital earnings). Thirty industries (out of a complete of 301) can account for almost the entire rise in inequality from the late Nineties to the late 2010s. In these 30 industries, ‘mega companies’ (which make use of 10,000 or extra) have seen a large surge in employment. This column describes a few of our major findings.

Business-level variations drive growing inequality

Industries drive growing inequality. Determine 1 experiences our measure of inequality, which is the variance of log (annual) labour earnings. We estimate inequality in three seven-year intervals: 1996-2002, 2004-2010, and 2012-2018. That is damaged down into the inequality inside companies and between companies. The between-firm part of inequality is additional damaged down into that which happens between companies in the identical {industry} versus that which happens on the {industry} degree.

Inequality within the US has risen over time. In Determine 1, we present that the variance of log earnings has elevated from 0.794 in 1996–2002 to 0.916 in 2012–2018. The variance of log earnings is the sum of three parts. Most inequality happens inside companies, and this dispersion elevated from 0.512 to 0.531, accounting for 14.9% of the rise in inequality. Amongst companies in the identical {industry}, dispersion elevated from 0.112 to 0.140, accounting for 23.1% of the rise in inequality. Dispersion between industries elevated from 0.170 to 0.245, accounting for 61.9% of the rise in inequality. Due to this fact, many of the rise in inequality has occurred throughout industries.

Determine 1 Between-industry variations account for many (61.9%) of accelerating inequality

Notes: Individuals with annual actual earnings > $3,770 working at employers with no less than 20 staff in 18 US states.

A small share of industries dominate the rising between-industry inequality

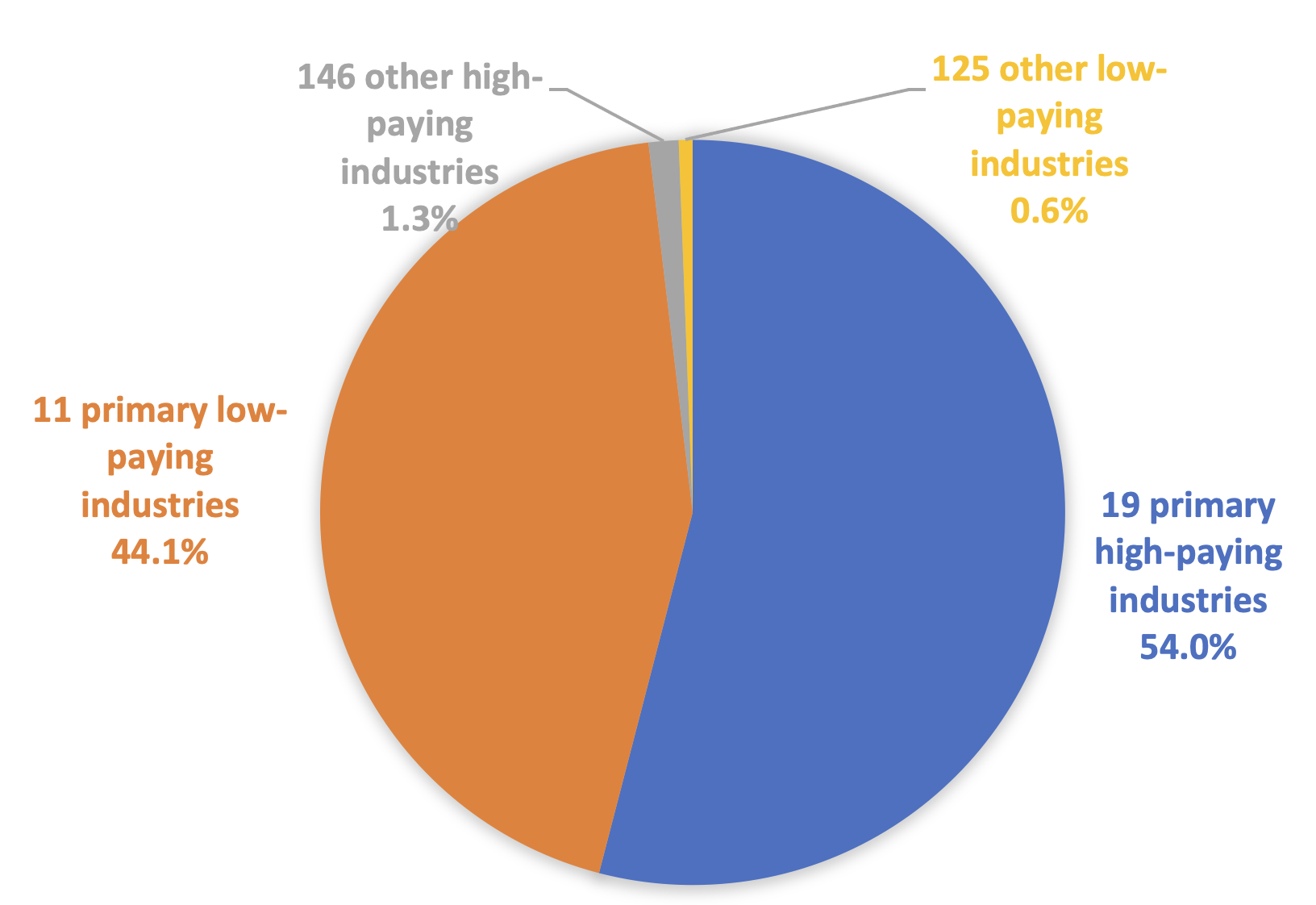

About 10% of industries account for the entire between-industry rise in inequality. We think about 301 industries outlined utilizing the North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS) on the 4-digit degree. We classify industries primarily based on whether or not they are likely to pay roughly than the common, in addition to their contribution to inequality. Thirty industries account for no less than 1% (constructive) of the rise in between-industry inequality. One other 271 industries every contribute lower than 1% to between-industry inequality.

The contributions of various industries to between-industry inequality are proven in Determine 2. Recall from Determine 1 that between-industry inequality (the inexperienced area of Determine 1) accounts for 61.9% of the full enhance in inequality. The 30 industries that contribute most to growing inequality clarify almost all (98.1%) of the between-industry contribution to inequality – regardless of using lower than 40% of the workforce. Of those 30 industries, 19 are high-paying and account for 54.0% of the rise in between-industry inequality; 11 are low-paying and account for 44.1% of this enhance. The opposite 271 industries account for just one.9% of rising inequality.

Determine 2 Thirty industries (of 301) account for almost all of rising between-industry inequality

Notes: Individuals with annual actual earnings > $3,770 working at employers with no less than 20 staff in 18 US states.

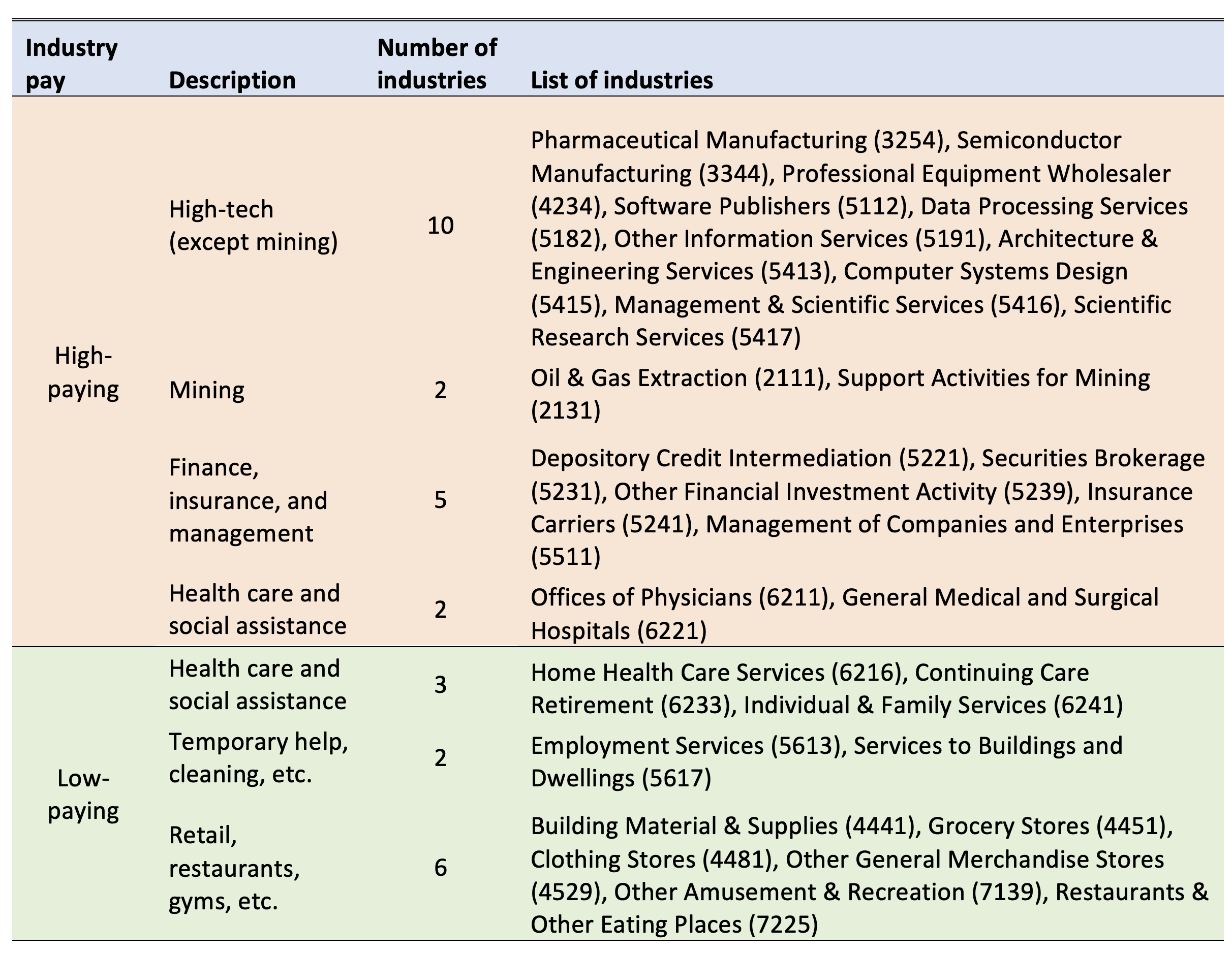

What are the industries that drive growing inequality? Figuring out these can yield insights into its causes. For instance, adjustments in know-how can result in will increase in inequality (Bloom et al. 2021). We subsequently listing in Desk 1 the 30 industries that contribute no less than 1% to the rise in inequality.

We begin with the 19 high-paying industries. A minimum of ten of those industries have been outlined as high-tech in phrases STEM depth in accordance with the factors of Hecker (2005) and Goldschlag and Miranda (2016). Two high-paying industries are in mining, together with help actions similar to drilling oil wells. The contribution of those industries is probably going associated to the shale oil increase (e.g. Decker et al. 2016) 5 high-paying industries contain finance, insurance coverage, or company headquarters. The outsized function of those industries might replicate restructuring and consolidation which have adopted monetary deregulation (e.g. Krozner and Strahan 2014).

Well being care and social help consists of each low-paying and high-paying industries. Two high-paying industries embody doctor workplaces and hospitals, through which appreciable consolidation has occurred (e.g. Fulton 2017, Cooper et al. 2019). Of the three low-paying industries, two deal primarily with look after the aged, together with each in-home care (e.g. hospice) and retirement properties. The remaining low-paying {industry}, Particular person and Household Providers, consists of adoption and foster care, companies for individuals with disabilities, and disaster hotlines.

The 9 remaining low-paying industries may be divided into roughly two teams. First, there are two industries that present help to companies and services. This consists of non permanent assist, the place employment has elevated (e.g. Luo et al. 2010), in addition to Skilled Worker Organisations (Dey et al. 2006). It additionally consists of cleansing and different help companies through which there was a considerable quantity of outsourcing (e.g. Dorn et al. 2018). The remaining six industries embody eating places, retail commerce, and gymnasiums, which have been reworked in current a long time with the rise of nationwide chains (e.g. Foster et al. 2016).

Desk 1 The 30 industries that drive inequality progress

Determine 3 Excessive-paying industries pay extra; low-paying industries make use of extra

Notes: Individuals with annual actual earnings > $3,770 working at employers with no less than 20 staff in 18 US states.

Excessive-paying jobs are paying extra; low-paying jobs are hiring extra

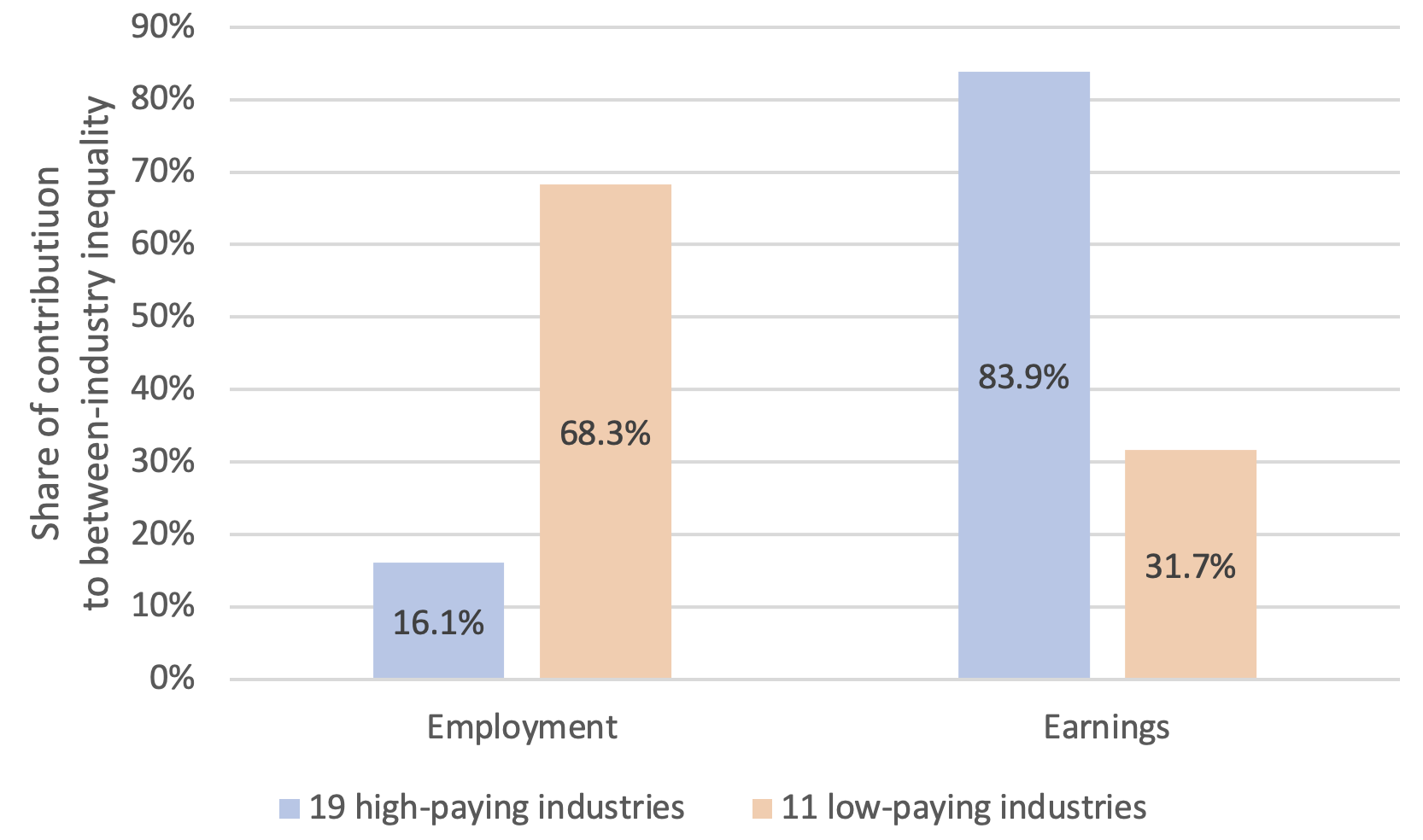

We now deal with the query of how a lot of accelerating inequality is because of employment versus earnings. Observe that adjustments in both employment or earnings can contribute to earnings inequality. For instance, eating places are typically among the many lowest-paying employers. When (comparatively) extra staff are employed by eating places, inequality will enhance. A decline within the pay of this {industry} would additionally enhance inequality.

Is growing inequality pushed by adjustments in employment or earnings? Determine 3 exhibits that there are sizeable variations within the reply to this query relying on whether or not the {industry} is high- versus low-paying. Amongst high-paying industries, 83.9% of the contribution to inequality is because of sturdy will increase in earnings, whereas any employment will increase in these industries solely account for less than 16.1% of this rise. In distinction, the employment among the many 11 most vital low-paying industries surged, accounting for 68.3% of their contribution to between-industry inequality. A way more modest decline in earnings in these low-paying industries explains the remaining 31.7%.

Determine 4 Rising between-industry inequality is attributable to elevated sorting, segregation, and dispersion in pay premia

Notes: Individuals with annual actual earnings > $3,770 working at employers with no less than 20 staff in 18 US states.

Extra high-earnings staff are employed by high-paying industries, and amongst different extremely paid staff

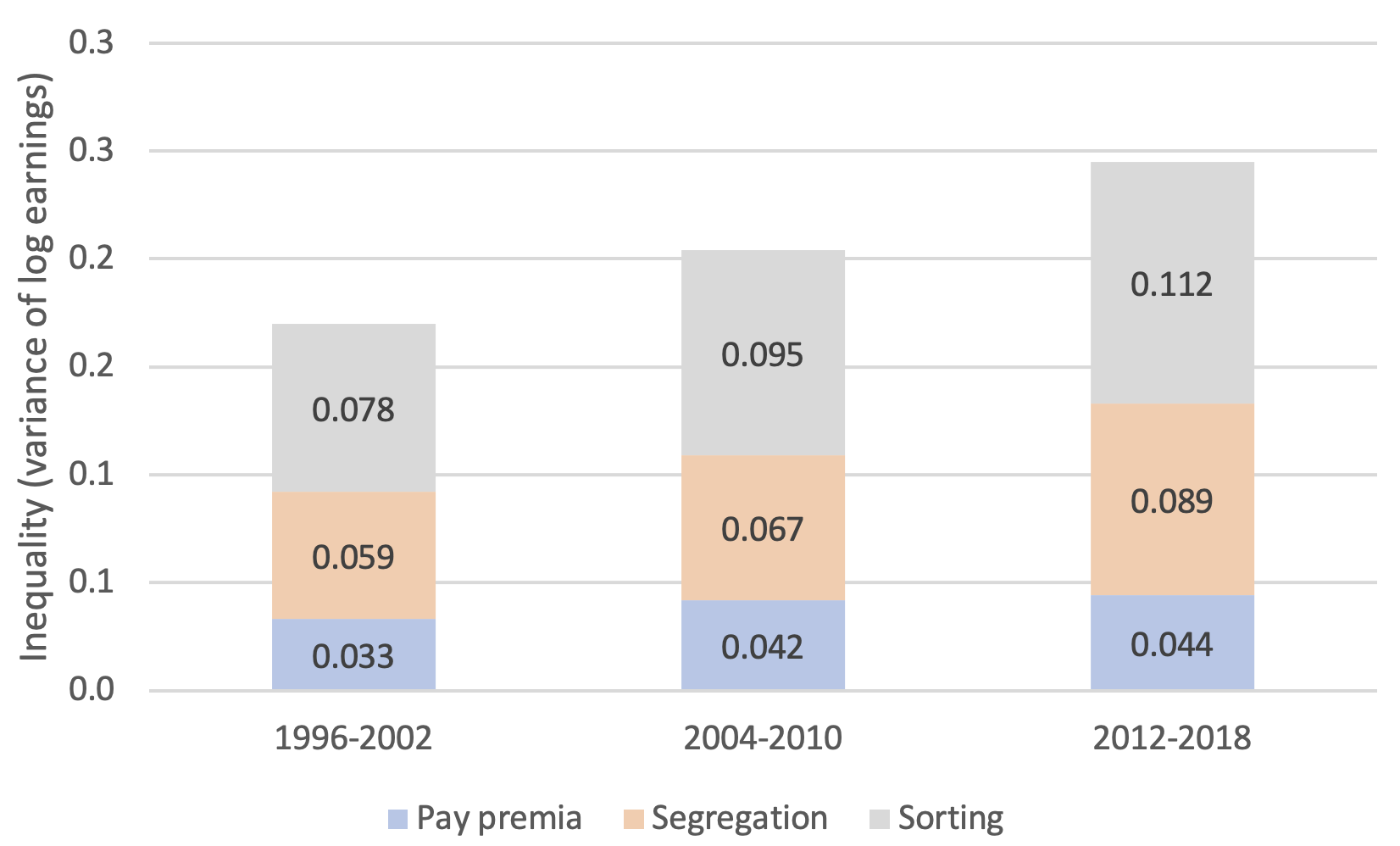

Following the pathbreaking work of Abowd et al. (1999), Card et al. (2013), and Music et al. (2019), we think about the query of the extent to which adjustments in inequality are pushed by staff or companies, which is particularly vital for understanding the contribution of high-paying companies and industries to inequality. Do high-paying companies supply bigger premia? Or are they hiring extremely paid (i.e. extra pricey) staff? As Music et al. (2019) show, there are three channels by means of which variations amongst employers contribute to inequality. These are:

1. Pay premia: some companies supply better earnings to any employee

2. Sorting: high-paying companies make use of extra extremely paid staff

3. Segregation: extra extremely paid staff focus amongst one another

We discover the relative contributions of those three phenomena to between-industry inequality in Determine 4. Sorting has the best function in growing inequality, and its contribution to the variance of log annual labour earnings elevated from 0.078 to 0.112 from 1996–2002 to 2012–2018. In different phrases, high-paying industries more and more make use of extremely paid staff. Extremely paid staff are typically employed in the identical industries (to the exclusion of staff with low earnings), and this rises from 0.059 to 0.089. Business-level pay premia have additionally widened considerably over time. This latter channel has had a smaller contribution to the variance of log earnings and rose from 0.033 to 0.044.

‘Mega agency’ employment has surged within the 30 industries that drive growing inequality

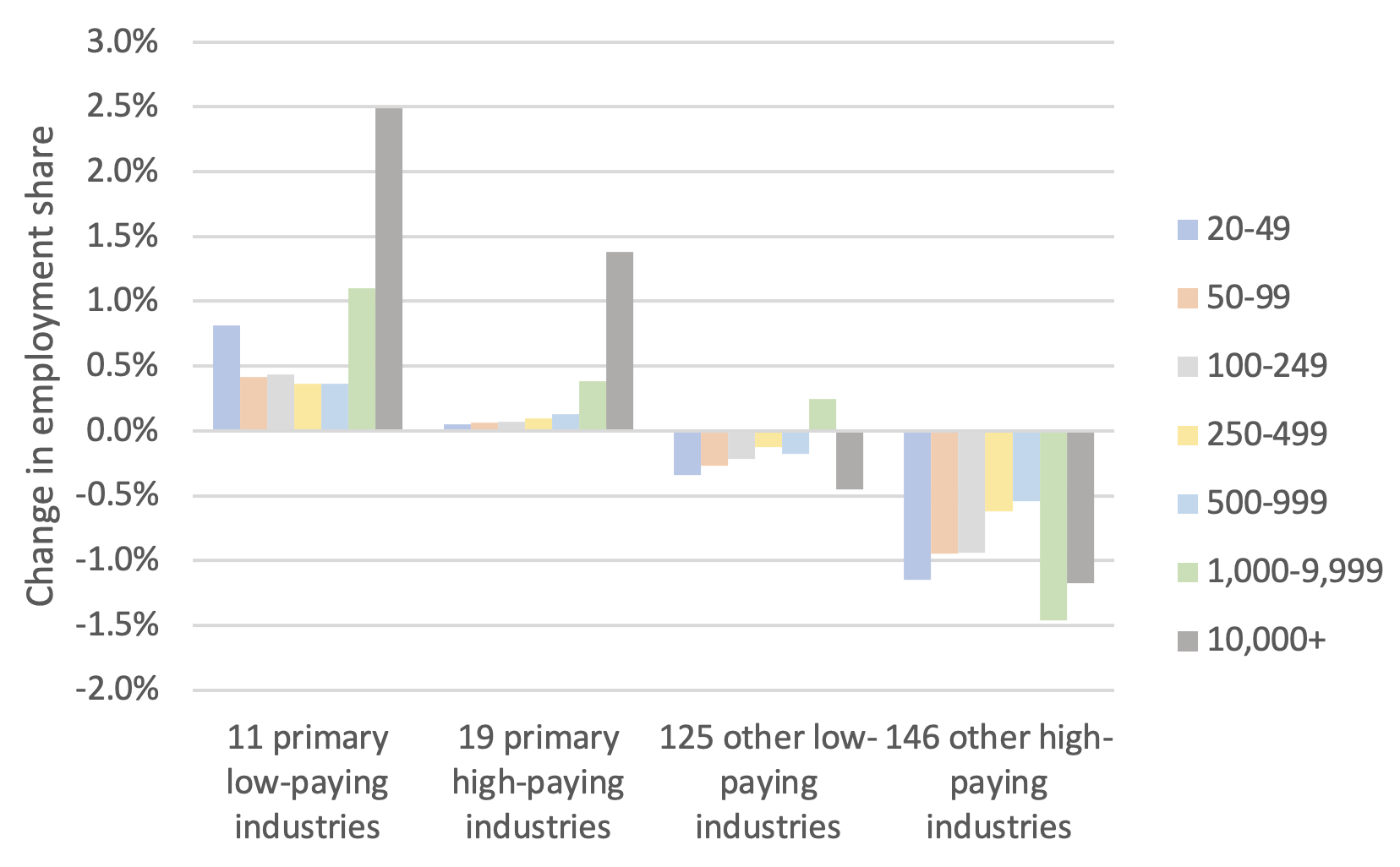

We now discover the function of ‘mega companies’ in growing inequality. By mega companies we imply people who make use of no less than 10,000 staff. Mega companies have been growing as a share of employment, as documented by Bloom et al. (2018) and Autor et al. (2020). In Determine 5, we break this enhance down in accordance with our 4 {industry} teams.

The rise in mega agency employment is sort of dramatic within the 30 industries that drive growing inequality. It’s particularly obvious within the low-paying companies that drive inequality by means of growing employment. The employment share of mega companies within the 11 low-paying industries that drive between-industry inequality elevated by 2.5 proportion factors, from 3.1% to five.6%. Observe that this means that hundreds of thousands of further staff had been employed in mega companies in low-paying industries: the full variety of folks employed within the US in 2018 was greater than 150 million (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2019). The employment share of mega companies within the 19 high-paying industries elevated by 1.4 proportion factors, from 3.2% to 4.5%. The employment share of mega companies within the different 271 industries fell.

Determine 5 The employment share of mega (10,000+ worker) companies elevated within the 30 industries that drive growing inequality

Notes: Individuals with annual actual earnings > $3,770 working at employers with no less than 20 staff in 18 US states. The labels 20-49, 50-99, and so on. denote the variety of staff on the agency. The denominator is complete employment throughout all dimension lessons and {industry} teams.

Conclusion

Industries drive current adjustments in inequality within the US. Thirty out of the 301 industries in our classification can clarify almost the entire rise in between-industry inequality. Continued examine of those industries might help make clear the mechanisms by which inequality continues to extend.

References

Abowd, J, F Kramarz and D Margolis (1999), “Excessive Wage Staff and Excessive Wage Companies”, Econometrica 67(2): 251-333.

Autor, D, D Dorn, L F Katz, C C Patterson, and J Van Reenen (2020), “The Fall of the Labor Share and the Rise of Famous person Companies”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 135(2): 645-709.

Berlingieri, G, P Blanchenay, C Criscuolo (2017), “Nice Divergences: The rising dispersion of wages and productiveness in OECD nations”, VoxEU.org, 15 Might.

Bloom, N, F Guvenen, B S Smith, J Music and T von Wachter (2018), “The Disappearing Giant-Agency Premium”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 108: 317-322.

Bloom, N, T Hassan, A Kalyani, J Lerner and A Tahoun (2021), “How disruptive applied sciences diffuse”, VoxEU.org, 10 August.

Card, D, A Cardoso and P Kline (2016), “Bargaining, Sorting, and the Gender Wage Hole: Quantifying the Impact of Companies on the Relative Pay of Ladies”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(2): 633-686.

Card, D, J Heining and P Kline (2013), “Office Heterogeneity and the Rise of West German Wage Inequality”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(3): 967-1015.

Cooper, Z, S Craig, M Gaynor and J Van Reenen (2019), “The Value Ain’t Proper? Hospital Costs and Well being Spending on the Privately Insured”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 134(1): 51-107.

Decker, R A, A Flaaen and M D Tito (2016), “Unraveling the Oil Conundrum: Productiveness Enhancements and Price Declines within the U.S. Shale Oil Business”, FEDS Notes.

Dey, M, S Houseman and A E Polivka (2006), “Producers’ Outsourcing to Employment Providers”, Working paper.

Dey, M, S Houseman and A Polivka (2010), “What Do We Know About Contracting Out in the US? Proof from Family and Institution Surveys” in Ok G Abraham, J R Spletzer and M Harper (eds), Labor within the New Economic system, Chicago: College of Chicago Press.

Dorn, D, J Schmieder and J Spletzer (2018), “Home Outsourcing in the US”, Unpublished.

Fernald, J (2014), “Productiveness and Potential Output earlier than, throughout, and after the Nice Recession”, NBER Macroeconomics Annual 29(1): 1-51.

Foster, L, J Haltiwanger and C J Krizan (2006), “Market Choice, Reallocation, and Restructuring within the U.S. Retail Commerce Sector within the Nineties”, Evaluate of Economics and Statistics 88(4): 748-758.

Foster, L, J Haltiwanger, S Klimek and C J Krizan (2016), “The Evolution of Nationwide Retail Chains: How We Received Right here”, in E Basker (ed), Handbook on the Economics of Retailing and Distribution, Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Fulton, B (2017), “Well being care market focus traits in the US: Proof and coverage responses”, Well being Affairs 36(9): 1530–1538.

Goldschlag, N and J Miranda (2016), “Enterprise Dynamics Statistics of Excessive Tech Industries”, US Census Bureau Middle for Financial Research.

Hecker, D (2005), “Excessive-technology employment: a NAICS-based replace”, Month-to-month Labor Evaluate 128(7).

Kroszner, R and P Strahan (2014), “Regulation and Deregulation of the US Banking Business: Causes, Penalties, and Implications for the Future”, in N L Rose (ed), Financial Regulation and Its Reform: What Have We Realized?, Chicago: College of Chicago Press.

Luo, T, A Mann and R Holden (2010), “The increasing function of non permanent assist companies from 1990 to 2008”, Month-to-month Labor Evaluate 133(8): 3-16.

Marin, D (2016), “Inequality in Germany: The way it differs from the US”, VoxEU.org, 23 June.

Mion, G, L D Opromolla and G Ottaviano (2020), “Dream jobs: A comparability of profession prospects in Portuguese companies”, VoxEU.org, 28 August.

Music, J, D Value, F Guvenen, N Bloom, and T von Wachter (2019), “Firming Up Inequality”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 134(1): 1–50.