A recent LA Times story on rising homelessness had a graph that caught my eye:

There’s little doubt that LA’s extremely high (and rising) rate of homelessness is partially caused by building restrictions that push up the cost of housing. But this graph suggests that non-economic factors also play a significant role in homelessness.

The wider (light blue) bars show the percentage of homeless in five racial categories. Don’t focus on the total share of homeless; look at the share relative to the share of total population (dark blue). Thus black homelessness is far higher than their share of the total population, white and Latino homelessness is slightly below their share of the population, and Asian homelessness is dramatically lower than their share of the total population. (I’ll ignore “other” and focus on the four specific categories.)

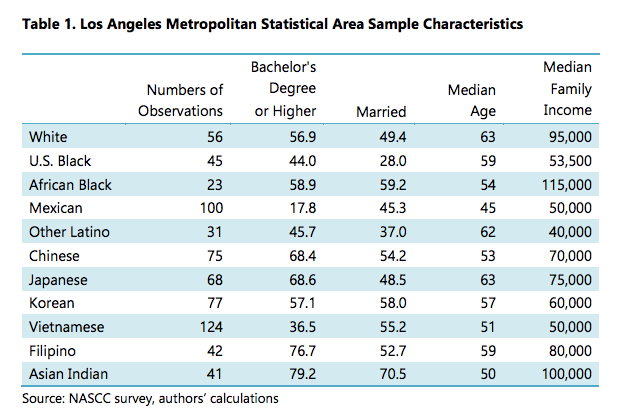

You might assume that this racial breakdown reflects economic factors, such as income differentials. But that is not the case. While Asians earn slightly more than whites on a nationwide basis, LA county is quite different. Many working class whites have moved away and those who remain tend to be relatively well off. The following table suggests that whites in LA earn slightly less than (Asian) Indian-Americans, but far more than the five East Asian groups. And these are median incomes, hence are not distorted by a few white billionaires in Beverly Hills. The typical white person in LA County is much better off than the typical Asian. Similarly, the typical black person in LA County is slightly better off that the typical Latino:

And yet, despite being more affluent than Asians, whites are many times more likely to be homeless than Asians. And that doesn’t surprise me at all.

And despite being less poor than Latinos, blacks are many times more likely to be homeless. And that doesn’t surprise me at all.

It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that LA’s whites are richer than Asians, but almost as likely to homeless as Latinos.

As I’ve mentioned in previous posts, most of America’s homeless are not living on the street. In colder cities like New York, the overwhelming majority live in places like homeless shelters, motels and trailers. But California is different—a sizable share of its homeless really do live on the streets. Anyone who has spent much time in LA will not be surprised to learn that blacks are more at risk of being homeless than Latinos, and that whites are more at risk of being homeless than Asians.

Many of the Asians and Latinos in LA are recent immigrants. Given how difficult it is to immigrate to the US, I’m not surprised that these groups would not have high rates of homelessness. A Chinese citizen who struggled through Panama’s Darien Gap is not likely to end up living on the streets. Nor is a Chinese citizen who came here as a grad student. And it’s not about income—a working class illegal Chinese immigrant making minimum wage in a restaurant is not likely to end up on the street. Homelessness has a strong cultural dimension. Low wage immigrants often live in extremely crowded housing. That sort of living arrangement is much harder to maintain for American-born poor who have severe drug or mental health problems.

Again, here I’m not talking about all homeless, but rather the subset that live on the streets in LA. If you look at America’s total homeless population, then economic factors play a somewhat larger role. That’s where policy initiatives to build more housing can help the most.

PS. Here’s an example of a LA couple that is not living on the streets (from an article on illegal migration from China):

A 47-year-old woman, surnamed Dai, was among the volunteers. She was living in a family hotel with her husband for $15 a night, 10 people to a room, 30 sharing a bathroom, she said.

During their three-month journey, she said, all their possessions were stolen, and they spent 20 days in immigration detention. They have an appointment with immigration authorities in September.

Since arriving in Monterey Park in February, Dai’s husband occasionally picks up landscaping jobs, and she sometimes cooks for senior citizens.

And another example of a poor person that will not be living on the streets:

Wang, 53, said he was a cardiologist in China. He quit practicing medicine years ago because the salary in remote Gansu province was paltry — about $700 U.S. a month, he said. . . .

With his limited English, Wang doesn’t expect to ever practice medicine again. After he gets his work permit, he hopes to become an Uber driver and then a long-haul truck driver.

“I knew the U.S. would be this type of environment. Mutual respect. Even if you’re not upper class, you can still make money,” he said in Mandarin tinged with the brogue of his native Shandong province. “You can work any kind of job for an hour and make enough to eat for a week.”

PPS. In the past, I’ve pushed back against the claim that America was trending toward being a non-white country. I believe these racial categories are becoming increasingly obsolete. Within 50 years, people will view the situation more in class terms, with many Latinos being lumped in with working class whites, and many Asians being lumped in with middle class whites. Intermarriage will accelerate these changes. One class might suffer more from obesity, another from depression. In the old days, the rich had more stuff. It would not surprise me at all if in the future the working class had more stuff, and the rich had more “experiences”. If you think that’s impossible, just recall that 120 years ago people would have thought you were a lunatic if you claimed that in the future the rich would be thinner than the poor.