Over at Alphaville, Robin Wigglesworth looks at whether ‘Greedflation’ (aka price-gouging) meaningfully contributed to Eurozone inflation. Specifically, Bank of England research suggests that while they “find no evidence of a rise in overall profits in the UK” they did notice that “companies in the oil, gas and mining sectors have bucked the trend” with “some companies… much more profitable than others.”1

I was pretty skeptical about Greedflation initially; when i ranked the top 15 sources of US inflation in mid-2022, “Corporate Profit Seeking” was at the bottom, ranked 13 out of 15 inflation causes.

But as time went on, more research and data became available. Slowly but surely, we came to learn that more companies were adapting to the pandemic era’s mix of rabid demand and supply chain snarls with a specific approach choosing “Price over volume.”

The first person to identify this was Corbu’s Samuel Rines. (Twitter) He first began discussing the corporate preference for maintaining margin in 2022; over time, he observed some companies had pricing power for both price AND volume. Soon after, “Price over volume” began to morph into “Price AND Margin” (PAM).

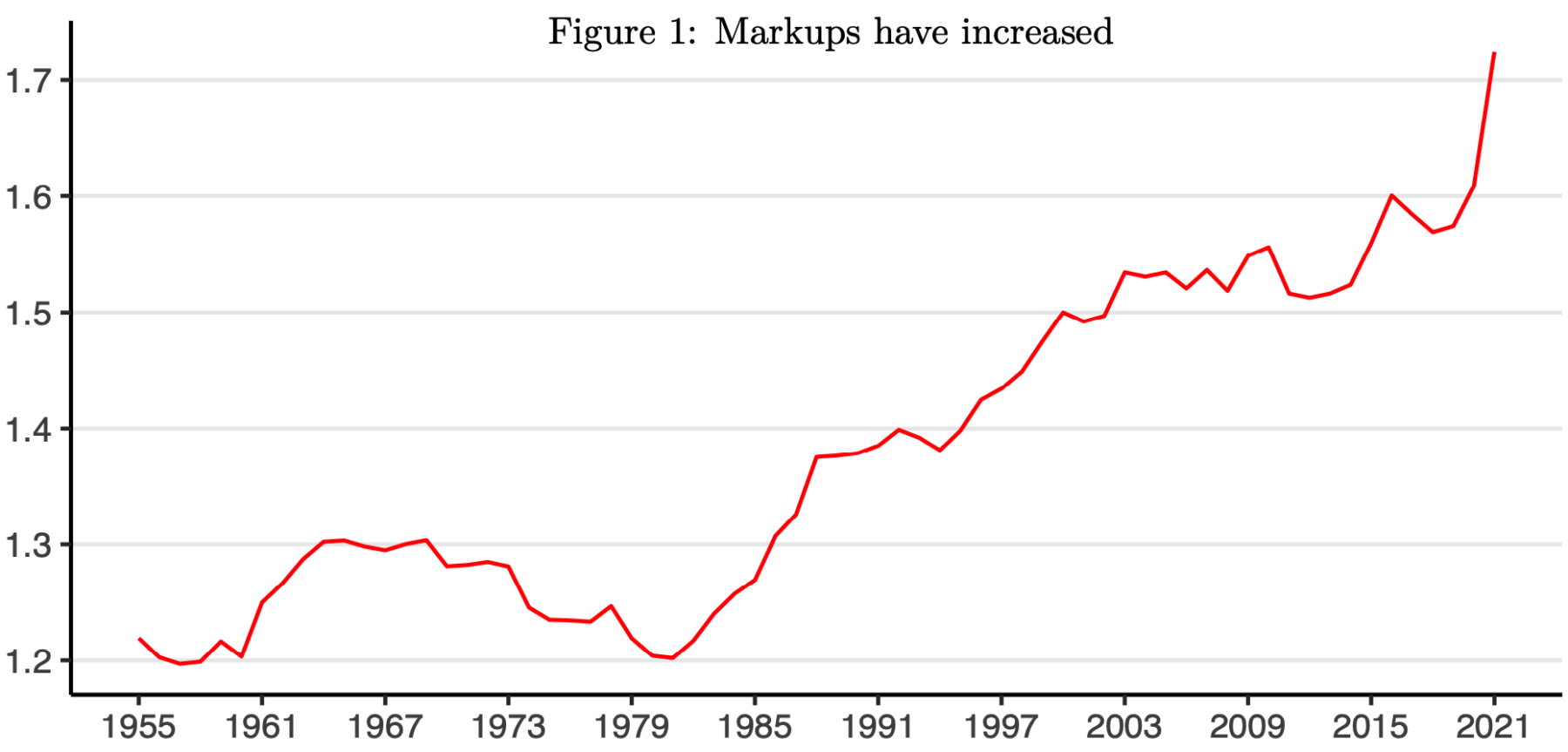

It’s the kind of subject ripe for academic analysis. Mike Konczal, director of the macroeconomic analysis program at the Roosevelt Institute, wrote a report, Prices, profits, and power. (See charts above and below) The focus was on annual net profit margins. It was about 5.5% in the 1960 to 1980 era. In the ZIRP decade of ultra-low rates in the 2010s, it rose to 6%. In 2021, it shot up to 9.5%.

That’s a huge, unexplained increase:

Fortune covered Greedflation on July 11, 2022: “There’s a fascinating debate playing out about markets, prices and inflation. Do companies raise prices because they have to, in order to keep pace with inflation? Or, sensing an opportunity to notch higher profits, do they take advantage of an inflationary environment to raise prices, thereby fueling inflation?” (emphasis added)

There are other sources of price increases, including hyper-regulated localities, especially in energy and housing. In August 2022, Vox suggested that if you were mad about inflation you should blame your local officials.

The drip of data made me wonder how much I underestimated greedflation initially. As consumers, we often do not (and cannot) see many of the inputs into final unit prices. Consider The Hidden Fees Of Ship Cargo:

“A cadre of ocean carriers are charging exorbitant, potentially illegal, fees on shipping containers stuck because of congestion at ports. Sellers of furniture, coconut water, even kids’ potties say the fees are inflating costs.”

As ballooning costs hit the wallets of American families, the global ocean shipping industry is enjoying its most profitable period in recent history. In the first quarter of 2022, the biggest carriers’ operating margins hit 57%, according to one industry research firm, after hovering in the single digits before the pandemic.” (emphasis added)

Any industry enjoying its most profitable period in history gets my attention.

My bias is that I was on Team Transitory from the beginning. For sure, transitory took longer than expected, but as we learned earlier this week, it asserted itself again. But the risk of “stickier” inflation remains, driven in large part by corporate profits, aka Rines’ PoV and PaM:

“In rare situations—such as an economy’s reopening after a pandemic—widespread knowledge that costs are rising allows businesses to raise their prices knowing that their competitors will act in the same way, according to a paper by Isabella Weber, assistant professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and her colleague, Evan Wasner.”

The “tell” about corporate profits and greedflation came after 2022 proved to be such a challenging year in the markets. Despite 500+ BPS of rate increases, a ~20% drop in the S&P500, and a 30+% drop in the Nasdaq 100, profits have remained much better than expected:

“A comparison shows how extraordinary our current inflationary distress actually has been and still is. Unlike during the 1970s, corporations today wield sufficient market power to effectively protect their profit mark-ups (and, by doing so, to realize higher profits) during a time of inflationary stress that is comparable to that of the 1970s.”

Even as inflation has come back down, the aftermath is that price increases have held. Corporate margins and profits could be the reason why price increases will stick, even as CPI falls back to normal. The rate of price increases may have normalized, but the absolute price levels today are much higher.

As Emily Stewart observed, “What goes up may not come down. Like, ever.”

Let’s hope she is wrong…

See also:

Greedflation’ revisited (FT, November 16, 2023)

Profits in a time of inflation: what do company accounts say in the UK and euro area?

Gabija Zemaityte and Danny Walker

Bank Underground, 16 November 2023

Banana Ships And The Hidden Fees Of Ship Cargo

GCaptain, July 3, 2022

Prices, Profits, and Power: An Analysis of 2021 Firm-Level Markups

Mike Konczal Niko Lusiani

Roosevelt Institute June 2022

Why Is Inflation So Sticky? It Could Be Corporate Profits

Paul Hannon

WSJ, May 2, 2023

Profit Inflation Is Real

By Servaas Storm

Institute for New Economic Thinking June 15, 2023

The problem isn’t inflation. It’s prices.

by Emily Stewart

Vox, Nov 14, 2023

Previously:

Who Is to Blame for Inflation, 1-15 (June 28, 2022)

Has Inflation Peaked? (May 26, 2022)

Transitory Is Taking Longer than Expected (February 10, 2022)

The Tide of Price over Volume (April 21, 2023)

__________

1. There are lots of similarities between the United Kingdom and the United States, but plenty of differences as well. The experiences with corporate margin expansion during a period of inflation in the U.S. seem to have been markedly different than those in the UK.