cemagraphics

Investment landscape

This past year has marked a significant turning point in a number of trends that had fundamentally shaped the investment landscape of the last decades. Two in particular come to mind:

The first is the predictable return of inflation, which, following the enactment of increasingly irresponsible monetary and fiscal policy responses to each passing crisis, has finally accelerated rapidly in 2022, once again nearing double-digits. As described below, this will continue to have important ramifications for years to come.

The second trend that appears to have reached an inflection point concerns geopolitics, and the relative calm that prevailed between the world’s main powers since the fall of the Berlin Wall, which accelerated a period of globalization, international trade, and access to cheap labor and natural resources. However, this past year saw the return of a major armed conflict on the European continent, which many see as little less than a prelude to a period of increasing multi-polarity, de-globalization, de-dollarization, and perhaps even a wider confrontation between Western and Eastern blocks in the years to come. This too will have major implications for investors.

Consequently, as we’ve been suffering the brunt of an inflationary shock, central banks across the world have finally been compelled to start normalizing monetary policy. They’ve done so by raising interest rates at a very rapid pace over the past 12 months, the fastest of tightening cycles in recent times, and some of them have started to shrink their balance sheets – albeit very slowly. One might assume that doing so necessarily implies that public finances will also need to be redressed, as central banks have largely been enabling government deficit-spending by repressing interest rates for more than a decade. For their part, commercial banks – which are responsible for the vast majority of credit creation in the economy – have proceeded to restrict lending, as reflected in the precipitous decline in the growth of monetary aggregates into negative territory.

As we’re already seeing, these actions will likely help tame a resurging inflation. However, such a tightening of monetary conditions will also unavoidably lead to a slowdown in global GDP growth, which is largely driven by the growth in credit creation. Thus, the next big risk facing investors today is a recessionary shock.

Rapidly tightening financial conditions in an over-levered world also increases the risk of so-called ‘credit events’, in other words, when systemically important financial institutions get into financial distress, and central banks are forced to intervene or run the risk of contagion. The turbulence we witnessed in the UK gilts market this past fall is an example of this, and we wouldn’t be surprised if the next credit event once again finds its roots in the derivatives market. As a case in point, the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) recently went out of its way to highlight the staggering amount, close to USD 100 trillion, in payment obligations arising from FX and currency swaps/forwards, which are kept off-balance sheet and thus do not appear in standard debt statistics.

Against this backdrop, many believe that slaying the inflation dragon – all the while managing a ‘soft landing’ of the economy – is quite improbable. A more likely scenario is that the economy slows down meaningfully, and that ‘stresses’ continue to appear in parts of the financial system as monetary conditions get tighter. In such a case, history would suggest that it is only a matter of time before major central banks pivot back to easing monetary conditions, perhaps as early as 2023.

But importantly, where will inflation be by that point? Will another ‘rescue’ by central banks work this time, as it has without fail for many decades, or will it prompt another inflationary wave and turmoil in global financial markets? This, together with the ongoing geopolitical uncertainty, are some of the main preoccupations for investors as we enter 2023.

Financial markets

There has been no shortage of market drama this past year, as much pessimism has ensued from the developments described above. As is typically the case, the segments of the market that were most overhyped, overbought and overvalued have been reassessed and brutally re-priced, including cryptocurrencies, SPACs, and NFTs.

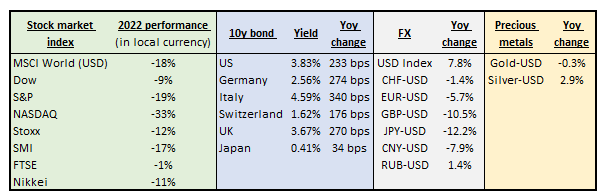

Refinitiv. All data as of Dec. 31st 2022

As shown in the table above, major equity indices across the world also fell quite sharply – and most recorded their worst year since the global financial crisis of 2008 – with U.S. equities and technology companies leading the way. For example, the ARKK Innovation ETF, which had become the poster child of a new paradigm for ‘growth’ investing, lost over two-thirds of its value. One of its largest holdings, Tesla, declined by a staggering 72%. Even mega-cap technology companies, that have become the bedrock of a market increasingly dominated by passively-managed investment strategies, declined significantly: e.g. Apple (-28%), Microsoft (-30%), Alphabet (-40%), Amazon (-51%), Meta (-65%), and Netflix (-52%).

By contrast, as investors reassessed their time preference in light of rising interest rates, ‘value’ stocks outperformed ‘growth’ stocks by a significant margin this past year – a trend that has ways to go before fully reverting back to its mean.

Looking beyond the U.S., other geographies might appear to have fared slightly better, but much of that outperformance is due to their weakening currency relative to the USD, with the U.S. Dollar Index up nearly 8% in 2022.

As anticipated, bond markets were no less turbulent, to the dismay of investors who traditionally seek some level of resilience in a so-called ‘balanced’ asset allocation. As a result of rising inflation and interest rates, bond prices ended their multi-decade bull run and fell meaningfully across geographies, with the iShares Global Government Bond ETF down over 18% in 2022.

In the U.S., Bloomberg’s index of US Treasuries posted its worst annual performance since the index’s inception in 1973, falling -12.5%. Sovereign bonds in the Eurozone saw even larger drawdowns, with a decline of -18.4%; whilst gilts fell -25.0% amidst the turmoil in the UK. It was also a very bad year for corporate credit, with double-digit losses across all major geographies.

As a result of falling bond prices, the amount of sovereign bonds with negative yields – which at its peak in December 2020 reached USD 18.4 trillion, or a quarter of global bonds outstanding at the time – has fallen to zero for the first time in roughly a decade. Thus, for the time being at least, investors will no longer be forced to pay for the privilege of lending their capital to sovereign governments, and some much-needed sanity has finally returned to the global fixed income market.

At the same time, yield curves have mostly flattened, and in the case of the U.S. fully inverted to levels unseen since the early 1980s, which typically signals expectations of a short-term economic slowdown and lower interest rates.

Overall, global stocks and bonds lost nearly USD 35 trillion in value in 2022, according to the Financial Times. So, despite some relief in the fourth quarter, 2022 will mainly be remembered as a very difficult year by most investors, when markets priced in the unpleasant consequences of higher inflation and interest rates, which are likely to impact the global economy in 2023.

As we’ve stated in the past, in what has been a world of monetary abundance, we want to mainly focus on owning scarce and productive assets, as well as maintain some level of optionality by holding liquid reserves. This very much remains the case as of today.

Editor’s Note: This article covers one or more microcap stocks. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.