by Charles Hugh-Smith

The unraveling of hyper-Globalization and hyper-Financialization will generate consequences few conventional analysts and pundits anticipate.

TikTok videos on ‘Quiet Quitting’–doing the minimum at work, giving nothing extra to the employer– have gone viral, and The Wall Street Journal quickly picked up the thread:

If Your Co-Workers Are ‘Quiet Quitting,’ Here’s What That Means Some Gen Z professionals are saying no to hustle culture; ‘I’m not going to go extra.’

The movement away from putting career first and sacrificing to get ahead financially is global: From the Great Resignation to Lying Flat, Workers Are Opting Out In China, the U.S., Japan, and Germany, younger generations are rethinking the pursuit of wealth.

Here are a few excerpts from the WSJ article:

“It isn’t about getting off the company payroll, these employees say. In fact, the idea is to stay on it– but focus your time on the things you do outside of the office.

Paige West, 24, said she stopped overextending herself at a former position as a transportation analyst in Washington, D.C., less than a year into the job. Work stress had gotten so intense that, she said, her hair was falling out and she couldn’t sleep. While looking for a new role, she no longer worked beyond 40 hours each week, didn’t sign up for extra training and stopped trying to socialize with colleagues.

Mr. Khan explained the concept this way: “You’re quitting the idea of going above and beyond.”

“You’re no longer subscribing to the hustle-culture mentality that work has to be your life,” he said.

Mr. Khan says he and many of his peers reject the idea that productivity trumps all; they don’t see the payoff.

“One factor Gallup uses to measure engagement is whether people feel their work has purpose. Younger employees report that they don’t feel that way, the data show.”

Josh Bittinger, a 32-year-old market-research director at a management-consulting company, said people who stumble on the phrase “quiet quitting” may assume it encourages people to be lazy, when it actually reminds them to not work to the point of burnout.”

There’s a lot to unpack here.

1. The nature of work has changed due to the dominance of capital and globalization.

The pressure to increase productivity has been increasing for decades even as everyday life has become more demanding. Even a 40-hour a week job can cause burnout when the workplace is a toxic pressure cooker.

Globalization has a role in this, as the Neoliberal “solution” is to make everything into a market. In terms of work, the net result is everyone is competing with the rest of the world for work in “tradeable” sectors.

This Neoliberal iteration of capitalism favors capital over labor on many levels. Capital is mobile and can enter and exit global markets in seconds. Labor does not have the same mobility.

Capital can find cheaper sources of labor somewhere on the planet, and can move and shutter factories, call centers, etc. at will to boost profits.

The net result is that labor has lost political and pricing power. Workers were basically told to accept lower compensation and security to keep their jobs.

A more pernicious expression of this dominance of capital over labor is the increasing demands for effort that isn’t compensated. This has many manifestations: the expectation that “everyone” will work overtime for free, take work home, be on call all weekend, etc.

Here’s an example: when chatting with a flight attendant a few years ago on a domestic flight, the attendant told me that their hourly pay stops when the aircraft’s wheels touch the runway. This isn’t the end of their work, of course, but it was the end of their pay.

Readers have sent me videos of clueless U.S.-based Big Tech interns who do no real work but who jet around to useless meetings, gorge on free food at lavish corporate canteens, etc., but the reality for most of the workforce is work is demanding.

Managers who once had secretaries (the “Mad Men” era) now are expected to do their own correspondence, etc.

Even being on call for random shifts reflects the powerlessness of labor and the dominance of capital, a dominance driven by the open-ended competition of Globalization and the enormous advantages offered to corporations and the already-wealthy by Financialization, which lowered the cost of capital to the financial elite while maintaining high rates of interest for the workforce.

All the “above and beyond” is essentially unpaid labor, a reflection of capital’s dominance of labor, whose share of the national income and political power declined for 45 years.

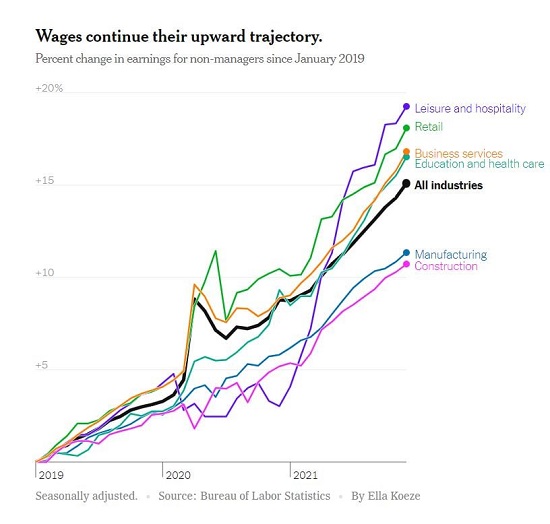

This long decline has finally reversed, as labor scarcities are changing the power relations of labor and capital.

2. Labor scarcities are permanent due to demographic and social dynamics.

One rarely examined trend is the remarkable rise of disability as an alternative to work.

This is a topic fraught with emotion, but the data shows that millions of workers are living on disability entitlements with disabilities that would not have qualified as permanent disabilities in previous generations.

The pandemic lockdown forced households to re-examine their budgets and expectations, and some percentage discovered they could get by on one income if they slashed discretionary spending.

These households discovered that having a job was now optional, enabling the second spouse to be pickier about what sort of work they would take.

Socially, the erosion of labor’s share of the economy has sparked a systemic reversal as Corporate America is now facing unionizing campaigns after decades of unquestioned power over employees.

The generational expectations of work are also changing, a reality reflected in “lying flat” and “quiet quitting.” Younger generations are re-assessing the sacrifices that must be made to claw one’s way into the upper-middle class and concluding the meager benefits (a huge mortgage, high-pressure work. no life beyond work, etc.) aren’t worth the sacrifice of one’s life.

Demographically, the 65+ million Baby Boom generation has continued working far longer than previous generations, but as Boomers leave the workforce, the replacement workforce isn’t of the same size or zeitgeist.

“Lying flat” and “quiet quitting” are further reducing the labor force of those willing to sacrifice themselves for employers seeking higher profits.

3. “Lying flat, quiet quitting” and labor scarcities are second order consequences of crushing systemic inequality.

If you detect a Marxist critique here, you’re correct. “Lying flat” and “quiet quitting” fit perfectly into a classic Marxist framework of capital’s dominance having second-order effects.

(First order effects: every action has a consequence. Second order effects: every consequence has its own consequence.)

Financialization gave capital unlimited access to low-cost credit and access to newly opened global markets for labor, goods, services, assets and risk.

This “nearly free money” and unfettered access to markets starved of credit and teeming with people with few options for cash work was the ideal set-up for capital to exploit cheap labor (at the expense of developed-world labor) and scoop up undervalued assets which could be financialized and sold for quick gains.

One first order effect of globalized Financialization is the rise of credit / asset bubbles, as low-cost capital competed for assets that offered yields or potential capital gains.

The second-order effect of Financialization is the cost of raising a family and owning a home soared out of reach for many workers.

In the most desirable cities, only the highest-paid workers can afford a house. Those with average jobs and pay have been priced out.

As the purchasing power of wages deflated, assets inflated. This is a global phenomenon. A Chinese worker making $10,000 a year has no hope of buying a $500,000 flat in a first or second-tier city. The average worker in Copenhagen or Tokyo is also priced out.

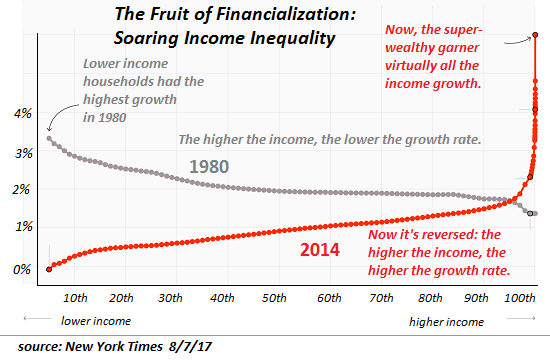

I’ve often showed charts which show the vast majority of all income and wealth gains in the era of hyper-Globalization and hyper-Financialization (roughly 1985 to the present) have flowed to the top.

Those relatively few workers with scarce skills benefited from capital’s need for specialized skills while the wages of the bottom 95% lost purchasing power.

Those with access to cheap capital reaped the vast majority of the gains from asset bubbles. This reality is documented in these links:

The Bill for America’s $50 Trillion Gluttony of Inequality Is Overdue (September 21, 2020, oftwominds.com)

Trends in Income From 1975 to 2018 (RAND)

The Top 1% of Americans Have Taken $50 Trillion From the Bottom 90% — And That’s Made the U.S. Less Secure (Time.com)

Lying flat and quiet quitting are second order consequences of crushing systemic inequality. There is no reason to sacrifice one’s life for employers’ profits when the supposed rewards are so far out of reach.

Japan offers an interesting case study of second-order effects of systemic inequality and a stagnant economy.

There is a thick overlay of face-saving propaganda about Japan, but beneath this heavily promoted gloss the social consequences are striking: arubaito and Hikkormori.

Arubaito is part-time, impermanent work, from the German word for work, arbeit. Those who don’t get into elite universities or who have given up aspiring to get into elite universities work low-level, low-pay jobs, often part-time. They spend their time pursuing hobbies and amusement, as they don’t make enough to get married, have kids and buy a house, and never will.

(Those with an interest in Japan’s unpublicized elite would do well to study the character of Kaburagi in the Japanese TV series Aibou – Partners in English.)

Hikkikomori, literally translated as “pulling inward, being confined,” is the total withdrawal from society, also known as acute social withdrawal.

These individuals withdraw into their room at home and rarely leave. Japan now has a serious social problem: what to do with these people once their aging parents die and there’s no one left to take care of them.

This may seem extreme but within the context of Japanese culture, this is a manifestation of giving up as a result of being unable to withstand the unrelenting pressures of high work and social expectations.

In my terminology, both arubaito and hikkikomori are manifestations of social defeat: there is no way for average people to achieve the dream of middle-class security and family and meet the absurdly demanding expectations for the “perfect” marriage, family, career, etc.

What are the second-order consequences of the global abandonment of the struggle to attain middle-class status and wealth?

Here are a few:

1. There won’t be a younger generation with the means or interest in buying all the global Baby Boomers’ overvalued assets.

2. Those inheriting their Boomer parents’ assets which they assume they can sell at today’s bloated prices will be shocked at the decline of the valuation once the massive supply overhang hits the market.

3. Younger generations with little interest in trying to make a lot of money to sock away for a distant retirement will not be funneling earnings into stocks, bonds, real estate investment trusts, etc.

The demand for financial assets will decline, and sellers will find a dearth of buyers. As demand for the vast oversupply of financial assets falls, so will price.

4. As labor demands an equalization of income and power, corporations will be hard-pressed to extract more profits from labor. Profits will be pressured for many reasons, including labor costs.

5. Consumption may hold up better than expected as younger workers spend their earnings on experiences and enjoying life rather than socking away money or devoting it to paying mortgages and property taxes.

6. The sacrifices required to live in high-rent cities–the equivalent of a mortgage–will push younger workers out of high-priced cities, eventually reducing demand and rents.

If cities decay per my forecast, this migration could gather momentum much faster than the mainstream expects.

This doesn’t exhaust the second-order effects of the destabilizing inequality generated by hyper-Globalization and hyper-Financialization, and the unraveling of these two forces will generate additional consequences few conventional analysts and pundits anticipate.

This essay was first published as a weekly Musings Report sent exclusively to subscribers and patrons at the $5/month ($54/year) and higher level. Thank you, patrons and subscribers, for supporting my work and free website.

My new book is now available at a 10% discount ($8.95 ebook, $18 print): Self-Reliance in the 21st Century.

My new book is now available at a 10% discount ($8.95 ebook, $18 print): Self-Reliance in the 21st Century.

Read the first chapter for free (PDF)

Read excerpts of all three chapters

My recent books:

When You Can’t Go On: Burnout, Reckoning and Renewal $18 print, $8.95 Kindle ebook; audiobook Read the first section for free (PDF)

Global Crisis, National Renewal: A (Revolutionary) Grand Strategy for the United States (Kindle $9.95, print $24, audiobook) Read Chapter One for free (PDF).

A Hacker’s Teleology: Sharing the Wealth of Our Shrinking Planet (Kindle $8.95, print $20, audiobook $17.46) Read the first section for free (PDF).

Will You Be Richer or Poorer?: Profit, Power, and AI in a Traumatized World

(Kindle $5, print $10, audiobook) Read the first section for free (PDF).

The Adventures of the Consulting Philosopher: The Disappearance of Drake $1.29 Kindle, $8.95 print); read the first chapters for free (PDF)

Money and Work Unchained $6.95 Kindle, $15 print) Read the first section for free

Become a $1/month patron of my work via patreon.com.