Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Oil-producing countries have stalled efforts to draft the first legally binding international agreement on cutting plastic pollution, proposing to move the focus to waste management rather than scaling down production, according to official observers at week-long UN talks in Nairobi.

The global gathering in the Kenyan capital was aimed at making progress on a deal for plastic equivalent to the 2015 Paris climate agreement. But the talks ended on Sunday evening without a plan to begin formal work on a draft treaty ahead of the next meeting, due to be held in Canada in April.

Blocking tactics by countries that argued against starting to frame a draft were “disastrous” and would prevent meaningful work being carried out before talks resumed, said Graham Forbes, head of Greenpeace’s delegation in Nairobi.

“More than halfway through the treaty negotiations, we are charging towards catastrophe,” Forbes said. “You cannot solve the pollution crisis unless you constrain, reduce and restrict plastic production.”

Saudi Arabia, Russia and Iran were among countries arguing that binding cuts to plastics production should not be within the scope of the negotiations, according to people present at the talks and documents released by the country delegates. Instead, they proposed a voluntary, “bottom-up” approach focused on improvements to plastic recycling.

Russia argued in a written statement on Wednesday that production of primary polymers, the fossil-fuel based chemicals of which plastics are made, “must not be discussed within the [UN plastics] process and shall not be part of the future instrument”. Iran’s delegation said that any treaty should “exclude the stages of extraction and processing of primary raw materials . . . since no plastic pollution is generated [then]”.

Last year’s UN environment assembly resolution on tackling plastics pollution, which kick-started the negotiations, said the “full life cycle” of plastics, including upstream production, should be addressed in a legally binding instrument by the end of 2024.

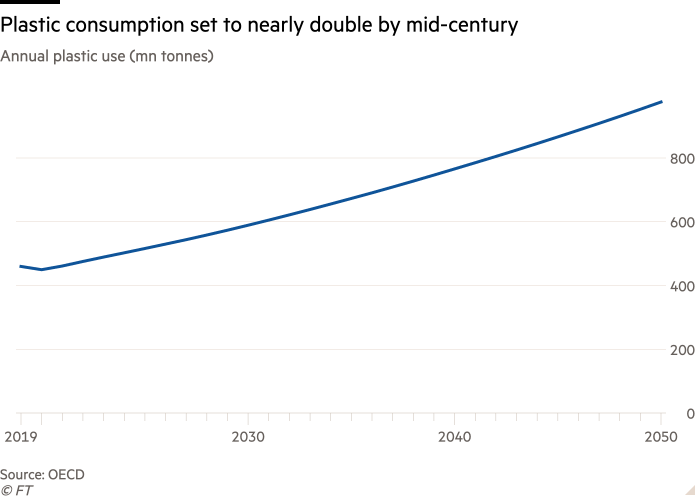

This could eventually create an agreement like the Paris climate deal — under which countries agreed to try to limit the rise in global temperatures to below 1.5C — but focused on addressing the risks to the climate, biodiversity and human health posed by the 400mn metric tonnes of plastic waste the UN environment programme estimates is produced globally every year. Less than a tenth of this is recycled.

Before the latest round of talks, a so-called high ambition coalition of states including Norway, Canada, the United Arab Emirates and the EU had called for any first draft to address binding reductions to plastic production.

Any measure to curb production would be a blow for fossil fuel companies. The market for the material is expected to drive a growing share of oil and gas revenues in coming years, offsetting weakening demand as the world transitions towards renewable energy, the International Energy Agency has said.

According to an IEA analysis, petrochemical products such as plastics and fertilisers are projected to make up more than a third of the growth in oil demand to 2030 and nearly half to 2050.

Petrochemical industry representatives were out in force in Nairobi, campaigning for solutions that did not require curbing production. According to non-profit advocacy group the Centre for International Environmental Law, 143 lobbyists representing the fossil fuel and chemicals sectors registered to attend the event.

The industry said more support was needed for “circularity” — in which products never become waste but are reused, recycled or maintained — and that it was investing billions of dollars in recycling infrastructure and packaging design.

Trade bodies representing the sector maintain plastic is essential in areas such as renewable energy and food and water sanitation. Supporting circularity “would avoid the unintended consequences of supply-side constraints of a material essential to meeting the UN’s sustainable development goals,” said Benny Mermans, chair of the World Plastics Council.

Companies exposed to single-use plastics are under increasing pressure to take responsibility for the waste they produce. European consumer rights groups have filed a complaint against food and drink producers Coca-Cola, Danone and Nestlé for misleading claims about the recyclability of their bottles, while New York state is suing PepsiCo over plastic waste pollution from its products in the Buffalo River.

Delegates failed to reach a consensus on giving the UN’s intergovernmental negotiating committee on plastic pollution a clear mandate to work on core negotiating points of the anticipated treaty, including on plastic production, chemicals in plastics, microplastics and single-use plastics, ahead of the April talks.

By Sunday evening, governments and observers had submitted more than 500 proposed amendments to the options presented for negotiation, with no decision on which to take forward.

Ana Rocha, global plastics policy director of the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives, said: “The bullies of the negotiations pushed their way through. Plastic is burning our planet, destroying communities and poisoning our bodies. This treaty can’t wait.”

But Inger Andersen, head of the UN Environment Programme, said that despite the setback, negotiators would “continue to be ambitious, innovative, inclusive, and bold” and use the talks “to hone a sharp and effective instrument we can use to carve out a better future”.

Additional reporting by Amanda Chu in New York