I call it an affair and not a relationship because I haven’t been faithful. I’ve given in to my impulses and left journalism for a short marketing stint, realising in the process that corporate life isn’t for me. One of the biggest reasons for coming back to this field was the chance to be part of a newsroom again.

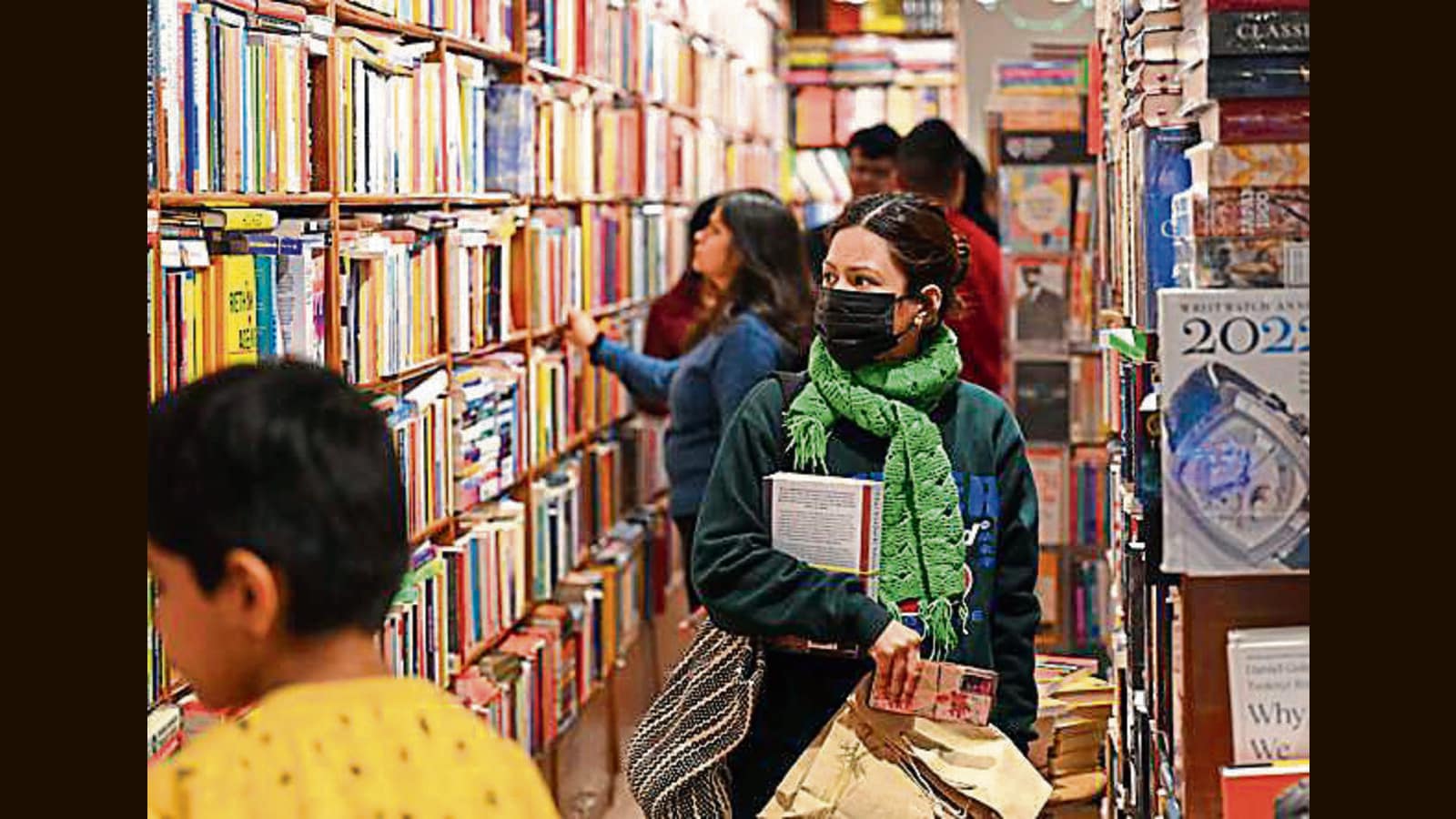

Professional infidelity aside, that night, the 9th-grade me got to see how a newspaper comes to life. I went on a reporting assignment, spoke to cops and hawkers, and came back to an office that was bustling even after sundown. It was a brightly lit newsroom with people returning from assignments, teasing and joking with each other, and discussing how they would divide their dinner dabbas.

Past 9 pm the chatter gave way to keystrokes. The editors pressed, the reporters sulked and we eventually “put the paper to bed”, as they say in the profession. That night I knew the career path I would choose.

Come for the excitement, stay for the pride

Five years later I found myself interning at another national daily. For two months I reported on crime, education, politics and even Bollywood. For six days a week I was the first person in the office and among the last to leave. I wanted to soak in every bit of this place and these people – full of life and proud of their work, even when complaining about low salaries and high EMIs.

The best part about that unpaid internship was that for those two months I was treated as an adult. After all, journalists know better than most not to underestimate people and will almost always accept an offer of help. I was given deadlines, allowed to tag along for interviews and asked for my opinion during edit meetings. The most adult matter I’d been consulted on up to this point was choosing the colour of the family car. (I picked blue, they went with metallic grey.)

Since then I’ve found myself in several newsrooms as a full-time employee. I’ve been part of edit meetings, conducted interviews at fancy hotels and met sources at rundown, cockroach-infested bars. In February 2021 I could (and really wanted to) go to the office and work on the Budget edition, despite the ongoing second wave of covid.

I love a good newsroom. It’s a place where sharp minds come together. There’s always someone willing to help – and without having to massage too many egos, in my experience. You can yell “what’s the current inflation index!”, and three voices from different directions will blurt out the answer. At the end of the day you can all head to the nearest watering hole to celebrate a newbreak or rue a missed opportunity.

This camaraderie is possible because you have plenty of common experiences with your fellow journalists. Reporters understand the pain of running to two press conferences at opposite ends of the city and delivering two copies on a deadline, and editors sympathise when you’re covering for someone else.

Not all fun and games

However, there’s a dark side to all this. During that fateful two-month internship I had the privilege of arriving early and staying in the newsroom as I lived just four stations away from the office and didn’t have any responsibilities to speak of at home. Thanks to my overworked and under-appreciated mother, my breakfast was ready at the dining table every morning and I could simply heat up some dinner when I returned home.

This also meant I could always say yes to a last-minute press club plan. I didn’t have to worry about when the last local would leave from CST, or time my exit to coincide with the metro from ITO. It was a rare privilege for me to participate and indulge in these experiences, all of which only enhanced my love and respect for newsrooms.

However, not everyone in a newsroom can participate in these bonding experiences because of family and other commitments . And some of these late-night activities are borderline unsafe. There are only so many times in your life you want to find yourself drunk and searching for a cab at 1.30 am near Connaught Place. This is why many of these late-night sessions end up being men-only. This leads to a real “boys’ club” culture in many newsrooms – I would know, I’ve been a part of them.

Then there’s the matter of teasing and playing pranks on newbies in their first couple of months. This may not always be taken kindly. Anecdotally, it can actually lower morale and it puts people on edge. Nobody wants to mess up right at the start of their career, or be seen as lacking a sense of humour.

I don’t want to speak on behalf of anyone else. However, I do know that if this piece was written by someone other than a man, it would probably have a far dimmer view of newsrooms.

Too much drinking and boys’ clubs aren’t the only less-than-stellar facets of newsrooms. A popular tradition in many is for new reporters to treat their colleagues after their first byline story is published. When I did this at my first job, I hadn’t even received my salary. By the time it was my turn to throw the party – a tradition that started with samosas but was quickly upgraded to chicken puffs and Cokes for dozens of colleagues – I found myself fishing out ₹3,200, or about 15% of my salary for the month. I can’t imagine how this would feel for someone who wasn’t financially supported by their parents and living in a foreign city, dealing with rent and other expenses.

There’s also the issue of enforced respect. In some newsrooms, there’s a strict, bureaucratic “sir/ma’am” culture (as I’m sure exists across offices in general). If you don’t attach the correct suffix to names you’re bound to ruffle a few feathers. Personally, I’ve erred on the side of caution until a senior editor asks me specifically to call them by name (or in some cases, just their initials). I prefer to work with people whom I can call by their first name, but to each their own.

Generation gap

Editors and other senior journalists are quick to claim that laziness is the main reason young journalists prefer to work from home. I’m sure it’s a factor. But you can’t tell me in all honesty that on some days you simply don’t feel like facing that hellish commute. Keep in mind that while most editors arrive at the office in AC comfort, young journalists rely on public transport. Wouldn’t that time in a bus or train be better spent, say, eating a relaxed breakfast and easing into the day rather than diving into the deep end? Wouldn’t that make you more productive than if you’d just been manhandled by a crowd at Dadar station?

This piece was written as a response to Maureen Dowd’s opinion piece ‘Requiem for the Newsroom’ in the New York Times, where she bemoaned the lack of enthusiasm from young journalists. Specifically, she attacked a young journalist’s unwillingness to commute to work. But older journalists’ memories might be a little different from what the younger lot is currently going through. Journalism, sadly, is in decline these days. With entire editorial teams being sacked the world over and more people switching to corporate gigs than ever before, the outlook is far more bleak than it was a couple of decades ago.

Surely, though, nobody does this job purely for the paycheque. That means there must be some passion left. This is reflected in the stubborn belief among journalists that ChatGPT will never be able to replace them entirely. But this passion doesn’t extend to daily commuting, late nights and office pranks. Perhaps it’s a good thing Gen Z journalists have a life outside the newsroom.

So the next time a journalist tells you they want to work from home, pay heed. They may have a good reason to for doing so.

Download The Mint News App to get Daily Market Updates.

More

Less