Weak investment, low productivity and inadequate education have condemned Latin America to a period of economic failure even worse than the “lost decade” of the 1980s, according to the top UN economic official in the region.

José Manuel Salazar-Xirinachs, new head of the UN Economic Commission on Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), said the stagnation of the past decade contrasted not only with the 5.9 per cent annual growth of the 1970s but also the 2 per cent achieved in the 1980s, a turbulent decade for Latin America characterised by a wave of debt crises.

“This is terrible, this really ought to be a huge red light,” he said of the descent into stagnation, with average annual economic growth in the decade to 2023 set to be just 0.8 per cent. “The challenge is how to return to this line of 5.9 per cent a year,” he said.

Salazar-Xirinachs, speaking to the Financial Times from ECLAC’s base in Chile, also called on the region’s three newest leftwing leaders to prioritise growth over a desire to share the spoils of wealth. Brazil, Colombia and Chile have all elected leftwing presidents in the past year.

“In general the progressives in Latin America have been preoccupied with distribution but not with wealth creation,” said the Costa Rican economist. “We need both and they go hand in hand.”

Latin America has grown more slowly than almost any other part of the world over the past decade. The region was hard hit by the pandemic, suffering more than a quarter of all recorded coronavirus deaths, despite having only 8.4 per cent of the world’s population.

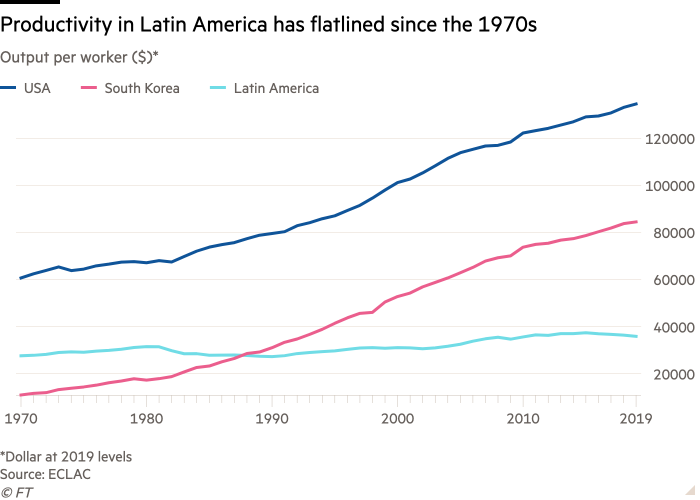

Salazar-Xirinachs said the underperformance was due to a lack of investment and poor education, both of which had hurt productivity. “We’re investing too little in infrastructure and we have an education system which is not delivering the talent we need in terms of numbers and quality,” he said.

Yet he also stressed that spending more money on education was not necessarily the answer, noting how his native Costa Rica had boosted education spending substantially but had not seen the expected results.

“We’re . . . at about 7 per cent of GDP but the Pisa scores are very bad,” he said, referring to the OECD’s benchmark for educational attainment. “There are countries [spending] 4.5 per cent with much better education systems. The problem is that, in the education industry, quality has been ignored.”

ECLAC, often known by its Spanish initials CEPAL, has long been wedded to “dependency theory” — the idea that raw material producers are trapped in an unfair global economic system that prevents them from moving up the value chain — and has in the past advocated state-led industrialisation as a response.

But Salazar-Xirinachs, who previously worked at the International Labour Organization and the Organisation of American States, said he was keen for the region to escape economic stagnation by adopting what he called “productive development”.

This meant harnessing public and private money to develop high value-added goods and tech-enabled services in sectors such as medical devices, electric vehicles, green energy and pharmaceuticals. This was best achieved by creating “clusters” close to universities and research institutes.

Salazar-Xirinachs said Spain’s Basque region had successfully used the model but that it had been used only sporadically in Latin America, for example in the Bogotá region of Colombia or in the automotive sector in Mexico.

“It needs to become a more coherent policy . . . and to leave to one side those debates about whether it’s the state or the market. What’s good about the [cluster] focus is that it’s a very pragmatic way to collaborate.”

William Maloney, chief economist for Latin America and the Caribbean at the World Bank, agreed that low investment and poor productivity were at the heart of the economic problems. “The region is looking to crack this nut of low job and productivity growth and there’s a lot of common ground to work on with CEPAL,” he said.

Other priorities included improving the efficiency of government spending, making tax systems more progressive and increasing the supply of trained mid-level technicians, engineers and managers, Maloney added. “The region has been very weak in technical capabilities,” he said.

Latin American countries trade less with each other than any other region, with their economies geared instead to export raw materials to the US, Europe and China.

Salazar-Xirinachs wants to see a greater focus on practical measures to facilitate inter-region trade, including trade in services, rather than the grand political declarations that have characterised past efforts at Latin American integration.

Trade negotiations have yielded sophisticated agreements with the US or Europe but not good regional deals.

“In the past, regional integration was seen as an alternative to insertion in the world economy,” he said. “Now it’s clear that it’s more complementary. For Latin America to successfully become part of global value chains, it needs regional chains of production.”

Charts by Rafe Uddin in London