Jamaica is admittedly not the biggest economic story of the past decade, but some parts of the FT Alphaville empire (cough, the Oslo outpost at least) reckon that it is at the very least one of the most intriguing.

A few years ago FTAV ran a chunky two-part investigation into how Jamaica found itself circling the economic drain in 2013 — after spending over half its time as an independent country in various IMF programmes — but by 2019 had managed an improbable escape and impressive recovery.

Unfortunately, Covid-19 brutalised Jamaica right after that, hammering the country’s open, tourism-dependent economy and threatening to undo a decade’s worth of hard work. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has been another hit, lifting inflation and further blowing out Jamaica’s current account deficit.

So it’s heartening to see the latest assessment of the IMF and its executive board, which landed in our inbox yesterday. With our emphasis:

Over the past few years, Jamaica has been buffeted by a difficult global environment — from COVID, the war in Ukraine, and the ongoing tightening of global financial conditions. Supported by sound policy frameworks and policies prioritizing macroeconomic stability, the economy is now recovering strongly. As COVID waned, stopover flight arrivals had rebounded to pre-crisis levels, and 2022 real GDP growth is expected to be around 4 percent. Pushed by global factors — in particular, the impact of the war in Ukraine on commodity prices — inflation has risen above the central bank’s target band but is expected to decline during the course of 2023. High commodity prices have resulted in an increase in the current account deficit. However, international reserves remain at healthy levels. The financial system is well-capitalized and liquid.

The outlook points to a continued recovery in activity and inflation falling back within the Bank of Jamaica’s target range by end-2023. Nonetheless, global risks remain high. The war in Ukraine may push commodity prices higher, a stronger-than-envisaged tightening of global financial conditions may curb capital flows and reduce remittances, and new COVID variants could disrupt tourism and trade. The authorities’ response to recent shocks has been well designed. The fiscal policy response to COVID was nimble, supporting the economy in 2020 but then quickly resuming a downward path for the debt as the impact of the pandemic faded. Similarly, the response to the upward surge in fuel and food prices was to allow for full pass-through while providing targeted support to the poor within the existing fiscal envelope. The Bank of Jamaica has followed a data dependent tightening of monetary policy to counter the inflationary impulse arising from the rapid recovery in demand and increases in global prices. These policies have struck the right balance in responding to shocks, protecting the vulnerable, countering inflationary pressures, and further securing debt sustainability.

This was echoed by the IMF’s board, which reviewed the Fund’s recent Article 4 report on Jamaica:

Executive Directors agreed with the thrust of the staff appraisal. They commended the authorities’ strong track record of building institutions and prioritizing macroeconomic stability, which together with a nimble and prudent policy response helped Jamaica navigate successfully the pandemic and other recent global shocks.

This is as close as the IMF comes to a standing ovation.

Just take a look at how Jamaica’s debt-to-GDP ratio has gone from a peak of 147 per cent in 2013 — one of the highest in the world, and WILDLY high for a small, poor country — to about 86 per cent at the end of last year.

And that’s after it spiked back above 100 per cent in 2020 after Covid-19 hammered Jamaica. By 2025 the IMF predicts it will fall to about 71 per cent. Still high, but almost half where it was just a decade ago.

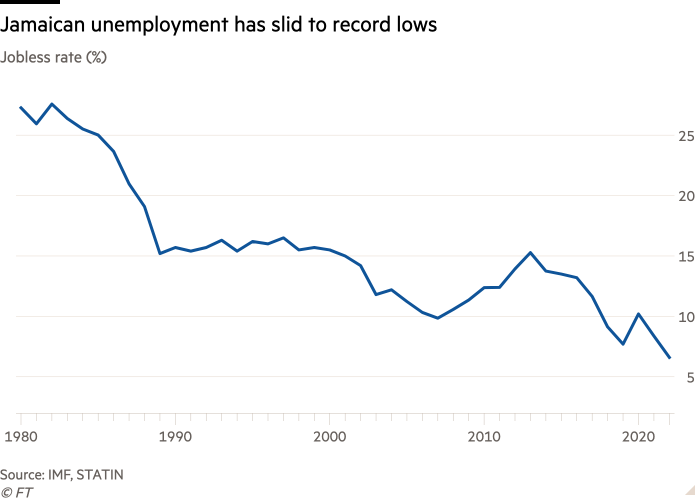

And this is not just about brutal austerity. Although tight fiscal policy has undoubtedly been a headwind to growth (the primary budget surplus is currently about 6.8 per cent, and was about 7.5 per cent for much of the past decade), the economy is now rebounding and unemployment falling again.

The Jamaican jobless rate fell to a record low of 7.7 per cent in 2019, before the pandemic the lifted it above 10 per cent again. The latest release from the Statistical Institute of Jamaica indicates that the unemployment rate declined to a new record low of 6.6 per cent last July.

There aren’t many happy economy stories out there right now, and Jamaica’s isn’t without its blemishes either.

The unemployment rate for younger Jamaicans remains high, at 16.7 per cent, and the economy is still some distance away from recovering back to its pre-pandemic level, after a 10 per cent contraction in 2020. And even before then, it was struggling to discover a faster gear despite a flurry of reforms designed to improve Jamaica’s growth potential.

But compared to where the country was a decade ago — when even Jamaica’s finance minister warned that the “survival of the Jamaican nation as a viable nation state” was at stake — this is as close to a miracle you’re ever likely to see.