ROME, Nov 03 (IPS) – On October 28, Armita Geravand, a 16-year-old Iranian teenager, passed away a month after she had been beaten by the police in the Tehran subway for not wearing the Islamic veil correctly.

Geravand’s death took place 13 months after Jina Amini´s, a 22-year-old Kurdish woman also beaten to death after being arrested in Tehran. She was also wearing her veil in the wrong way.

Amini’s murder, however, was the trigger for one of the largest protests that have shaken the Islamic Republic of Iran since its foundation in 1979. Hundreds of thousands of young women and men took to the streets chanting “Women, life, freedom” all across the country.

The Government responded with a wave of repression that resulted in hundreds of deaths and thousands of arrests between 2022 and 2023.

Removing the Islamic veil in public, or even burning it, has been a recurring gesture nationally to denounce the constant violation of women’s rights in Iran.

Such a powerful image became the key symbol in protests which also included demands from the country’s minorities.

Both the previous monarchical regime (1925-1979) and the current one have focused on building a national identity as a homogeneous Persian society, ignoring the rest of the nations of Iran.

Thus, Farsi is the only official language in a country where any expression of identities other than Persian is banned and even punished. But it turns out that minorities are the majority: more than 60% of the almost 90 million Iranians are not Persians.

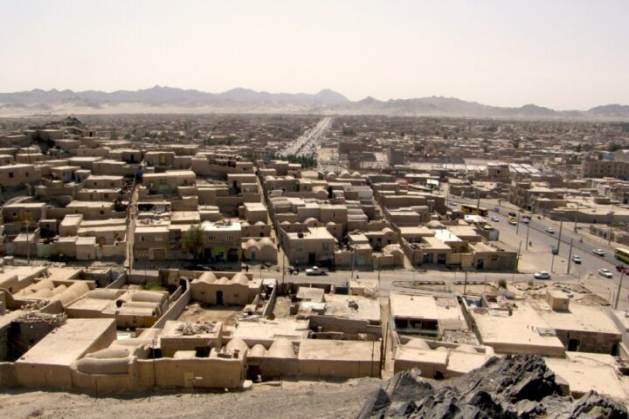

This is the case of the Baloch, a people numbering about four million in the extreme southeast of Iran, bordering Pakistan and Afghanistan.

A former political prisoner, Shahzavar Karimzadi is today the vice president of the Free Balochistan Movement, a political party banned in Iran that brings together Baloch people from three territories: Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

“We have been fighting for our most basic national rights for many years. We advocate for a secular, decentralized and democratic State, but that does not mean that we rule out our right to self-determination,” Karimzadi told IPS over the phone from London.

Apparently, Balochistan under Iranian control is the only corner of the country where the protest has not yet faded away. Karimzadi stressed that his people continue to demonstrate every Friday in Zahedan – the provincial capital, 1,100 kilometres southeast of Tehran – “despite the violence with which the regime responds.”

It’s true. An Amnesty International report published on October 26 denounced cases of torture of detainees in mass arrests in Balochistan that included children. The NGO urged the Iranian authorities to allow access to a UN mission to investigate human rights violations related to the protest.

The statistics speak volumes. Although the Baloch in Iran make up 4% of the country’s total population, a study by the Iranian NGO Iran Human Rights found that 30% of those executed by the State in 2022 belonged to this ethnic group.

From the mountains to the sea

Like the Baloch, the Kurds are also predominantly Sunni Muslims, an added stigma to their distinct ethnicity from the Persians under the ruling Shiite theocracy..

With a population estimated between ten and fifteen million, they live mainly in the northwest of the country, on the borders of Turkey and Iraq.

In an interview with IPS in the mountains between Iraq and Iran, Zilan Vejin, co-president of the Party for a Free Life in Kurdistan (PJAK), recalled that the slogan, “Woman, life and freedom” was coined by the Kurdish movement during a 2013 meeting.

“The protest started in Kurdistan led by women. From there, it spread throughout the country because it brings together people of all nationalities within Iran,” explained Vejin.

According to the guerrilla leader, calls against the mandatory use of the Islamic veil are “nothing more than the excuse for a revolt that calls for freedom and democracy.”

Vejin outlined his political project not only for Iran but for the region as a whole. It is a decentralized model, “a democracy built from the bottom up that advocates secularism, gender equality and the right of all peoples to develop their culture and language.”

It could be a solution that the Ahwazis of Iran could also accept.

They number about twelve million and concentrate on the shores of the Persian Gulf, right on the border with Iraq. They have paid for their Arab language and culture with decades of repression — from both the previous and current Iranian regimes.

Faisal al Ahwazi is the spokesperson for the Ahwazi Democratic Popular Front, one of the minority’s main political organizations. In a conversation with IPS by telephone from London, Al Ahwazi explained why his people had distanced themselves from the latest wave of protests.

“The repression we suffered in November 2019 is still too present. Back then, more than 200 Ahwazi protesters were murdered by the regime. That protest had no replicas in the rest of the country and we did not feel solidarity towards us,” lamented Al Ahwazi.

He highlighted the “lack of coordination” in the most recent protests and warned of dangers that may arise from a falsely executed regime change. “If the Persians want to remain in power, there will be a civil war,” said Al Ahwazi.

“Separatists”

One of the features of the last wave of protests in Iran has been the high level of participation by young people and their commitment to a “horizontal” movement. Although the absence of leadership has often been taken as a virtue, many analysts identify it as one of the reasons behind its failure.

Mehrab Sarjov, a political analyst and observer of the Iranian issue, also points out the lack of common goals and plans. “We don’t even know what kind of a country they vow for when the clerics are no longer there,” Sarjov explained to IPS from London over the phone.

The expert also recalled that Azeris make the country’s main minority and he highlighted their ties with both Turkey and Azerbaijan.

“Even if it´s Azeri, Kurdish, Arab or Baloch autonomists asking for decentralization and democratization of the country, they´re always labelled as ‘separatists’ by the Persians and automatically discarded,” explained Sarjov.

“It is the rhetoric of the ‘developed centre’ versus a ‘periphery’ whose economic and social backwardness is a consequence, they say, of its distance from that very centre,” he added.

In the absence of an inclusive project from the Persian core of the country, Sarjov points to the country’s minorities as “the main opposition force to the Government.”

But further steps need to be taken.

“Even the most secular and progressive Persians still do not recognize the rest of the peoples of Iran. It will still take time until they understand that they have to sit down and talk to them in order to articulate a movement with a chance of success,” concluded the expert.

© Inter Press Service (2023) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service