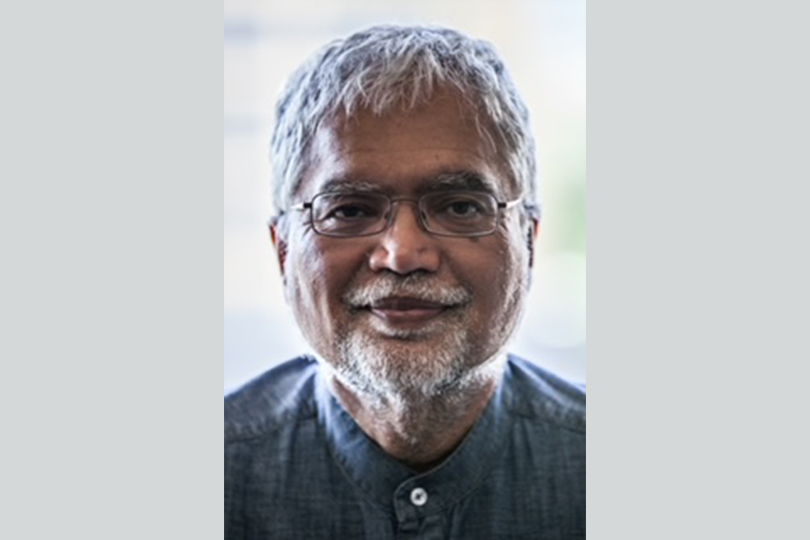

Annette Gordon-Reed is the Carl M. Loeb University Professor at Harvard University. Gordon-Reed won 16 book prizes, including the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, for The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family (2008). She is the author of six books, and editor of two. She was the Vyvyan Harmsworth Visiting Professor of American History at the University of Oxford (Queen’s College) 2014-2015, and was appointed an Honorary Fellow at Queen’s in 2021. Gordon-Reed served as the 2018-2019 President of the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic, and is currently president of the Ames Foundation. Her honors include fellowships from the Guggenheim and MacArthur Foundations, and the National Humanities Medal. She is a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Philosophical Society, and the British Academy.

Where do you see the most exciting research/debates happening in your field?

I think an exciting area for me is the comparative study of slavery in different societies. We’ve come to realize more and more how interconnected the system of slavery was across the world. Also, while making allowances for cultural differences, there’s a realization that there were points of commonality between slave societies in different countries. Actually, by seeing the differences that existed, we can learn more about the contingencies of being in a particular place.

How has the way you understand the world changed over time, and what (or who) prompted the most significant shifts in your thinking?

I suppose the most significant change has come from getting older. I have more patience than I did before. I understand how hard it is to get things done in the world. I tend to be more forgiving. The timeline for accomplishing things — life — is so short, and we can run out of time. Also, problem solving is easier with the benefit of hindsight. We can miss the difficulties of a particular moment, but with hindsight, we know what will happen, how, and why.

What can historiographical practices in America reveal about race relations and how they affect perceptions?

The old historiography of slavery really didn’t take into account the perspectives of enslaved people. That began to change decades ago, but the process has accelerated in the past couple of decades. That was a function of the marginalization of people of color in society in general. As more scholars of color are involved, new questions are being asked and answered. There’s so much to learn because so much had been ignored before.

In your latest book, On Juneteenth, you provide both a personal and historical account of Texas and its journey to Juneteenth. What were/are the key impacts of this journey, and how much has Texas since changed?

Well, I had the occasion to think about my family in a different way. I learned things about some of my ancestors that I didn’t know. That was good. It has made me want to investigate more deeply. I think about people who were pretty much just like me who did not have the opportunities that I had growing up. It makes me disinclined to despair and think that nothing could be done to make changes. They worked under unimaginably bad circumstances and made things easier for me. I feel I have an obligation to try to do the same for the next generations.

Texas has changed and remained the same. Of course the racial problems persist. But there are more opportunities for Black people than there were when I was growing up. The problems of race and class remain. And as Texas has entered this phase of hostility towards truthful history, at least in some quarters, it’s very important to be willing to stand against efforts to minimize the role of slavery and distort the history of race relations in the state.

You have written extensively on Thomas Jefferson and his links to slavery. Why is this an important topic when discussing American history and its contemporary impacts?

He was a major figure in American history. He wrote the Declaration of Independence and he enslaved people. His life story presents the American paradox in stark terms. We should think about that. We are still living with the legacies of slavery, and the study of Jefferson and slavery at Monticello is a way to keep that in mind.

In June 2020, you wrote about how popular resistance to white supremacy in the USA and global protests are a sign of hope. In the wake of the recent shooting in Buffalo targeting Black Americans, is it time to consider how the American political system should play a greater role in the nation’s struggles with racism?

The struggle against racism should be a part of our politics and a part of our culture in general. It has always been implicated in the treatment of people of color. Government policy determined that treatment and continues to do so today. It’s not a trivial matter at all. Our future really depends on working to bring all Americans into full citizenship.

As a scholar of legal history, what role does academia play in anti-racist discourse, and how can it move forward in this regard?

Academics can make a contribution through their scholarship and their teaching. There’s so much literature out there about race in this country, and it presents an opportunity to have discussions about this very serious topic. And of course, we write about the subject. Public history sites have increasingly relied on the work of academic historians as they tell the history of given sites. I think academia’s success in helping to broaden the narrative of American history is partly responsible for the backlash that we see now against teaching history in a more open way.

What is the most important advice you could give to young scholars of International Relations?

My advice is to pay attention to history, but not feel that we are hostage to it. It’s possible to change course. History doesn’t have to repeat itself. The contingencies are always there and are important. But it is still useful to know about the way people did things in the past, how they avoided mistakes, how they made mistakes.