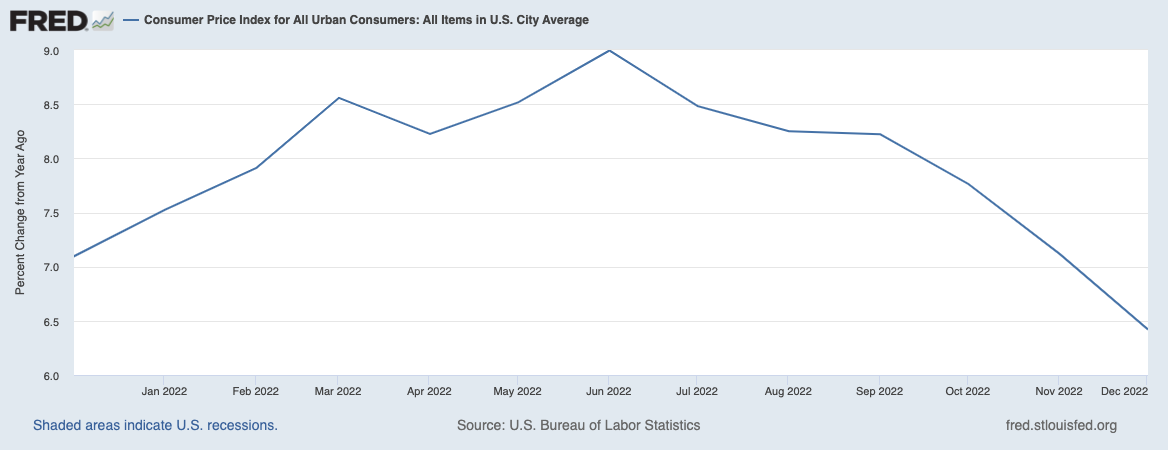

CPI for December came in as expected pretty much right on the nose showing a decrease in core inflation driven primarily by falling gasoline prices.

Some in the media have credited the aggressive action by the Federal Reserve in helping to lower rates of inflation, but I have a decidedly different view: Inflation has come down not because of but despite the rate increasing regime of the Federal Reserve.

If that sounds somewhat counterintuitive, allow me to explain my thought process by looking at five major aspects of prices:

1. Labor

2. Housing

3. Semiconductors

4. Energy

5. Shipping

Prices in each of these have been driven by factors outside of low rates and cheap cost of capital; the increases are specific to the period of pandemic lockdown, fiscal stimulus, and economic reopening in the United States and Europe (China’s reopening has not yet found its way into deflationary prices yet).

Consider:

Labor: For three decades, median (and below) wages have been deflationary, lagging productivity, corporate profits, C-Suite comp, and inflation. Credit the combination of globalization (cheap foreign labor), automation and productivity gains.

Numerous factors have reduced the potential labor pool: Decreased in immigration, record new business launches (self-employed), 10 million workers out with long COVID (and almost half a million workers dead from Covid); increase in disability, and plenty of early retirements. All of these have left America with a labor pool that is anywhere between two to four million workers short, forcing employers to compete for workers.

Housing: Following the Great Financial Crisis, developers and home builders focused on multifamily apartment buildings, somewhat ignoring single-family homes. The result is that the United States is anywhere between three to five million homes short of where demand suggests housing should be.

Low supply is only half of the problem: The Fed has doubled mortgage rates, pricing out about a million potential home buyers, and sending them into the rental market. The Fed has perversely made services inflation much higher.

Semiconductors: Reopening a semiconductor fab after it’s been shut for six to 12 months is not as simple as flicking a switch; it is a complex process involving an intricate supply chain.

Energy: Prior to the pandemic energy prices were about the same level as they had been a decade previous. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine nearly doubled the price of oil. As Russia’s military has faltered, the price of oil has come back down.

Shipping: The pandemic lockdown forced the economy to pivot from services to goods; demand soared as people were stuck living – and working – at home. This massive demand sent prices skyrocketing and revealed just how fragile the “Just-in-time” supply chain was.

In all of the above key sectors of the economy, the third is either having a de minimus impact on prices or actually having an inflationary impact (Apartment Rentals).

The Fed simply lacks the tools for dealing with the sorts of inflation confronting the economy today.

The key question going forward is not whether or not the Fed should declare victory and go home, but rather, as a reflection of their own lack of understanding of the drivers of this cycle’s inflation, exactly how much more unnecessary economic damage this group is going to cause…

See also:

The Fed May Finally Be Winning the War on Inflation. But at What Cost? (New York Times)

Fed, you’re so vain; you probably think this economy is about you (Stay at Home Macro)

Fed’s No-Rate-Cut Mantra Rejected by Markets Seeing Recession (Bloomberg)

Previously:

How the Fed Causes (Model) Inflation (October 25, 2022)

What the Fed Gets Wrong (December 16, 2022)

Behind the Curve, Part V (November 3, 2022)

When Your Only Tool is a Hammer (November 1, 2022)

Why Is the Fed Always Late to the Party? (October 7, 2022)