Kiran VB, 29, a resident of India’s tech capital Bangalore, had hoped to work in a factory after finishing high school. But he struggled to find a job and started working as a driver, eventually saving up over a decade to buy his own cab.

“The market is very tough; everybody is sitting at home,” he said, describing relatives with engineering or business degrees who also failed to find good jobs. “Even people who graduate from colleges aren’t getting jobs and are selling stuff or doing deliveries.”

His story points to an entrenched problem for India and a growing challenge for Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government as it seeks re-election in just over a year’s time: the country’s high-growth economy is failing to create enough jobs, especially for younger Indians, leaving many without work or toiling in labour that does not match their skills.

The IMF forecasts India’s economy will expand 6.1 per cent this year — one of the fastest rates of any major economy — and 6.8 per cent in 2024.

However, jobless numbers continue to rise. Unemployment in February was 7.45 per cent, up from 7.14 per cent the previous month, according to data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy.

“The growth that we are getting is being driven mainly by corporate growth, and corporate India does not employ that many people per unit of output,” said Pronab Sen, an economist and former chief adviser to India’s Planning Commission.

“On the one hand, you see young people not getting jobs; on the other, you have companies complaining they can’t get skilled people.”

Government jobs, coveted as a ticket to life-long employment, are few in number relative to India’s population of nearly 1.4bn, Sen said. Skills availability is another issue: many companies prefer to hire older applicants who have developed skills that are in demand.

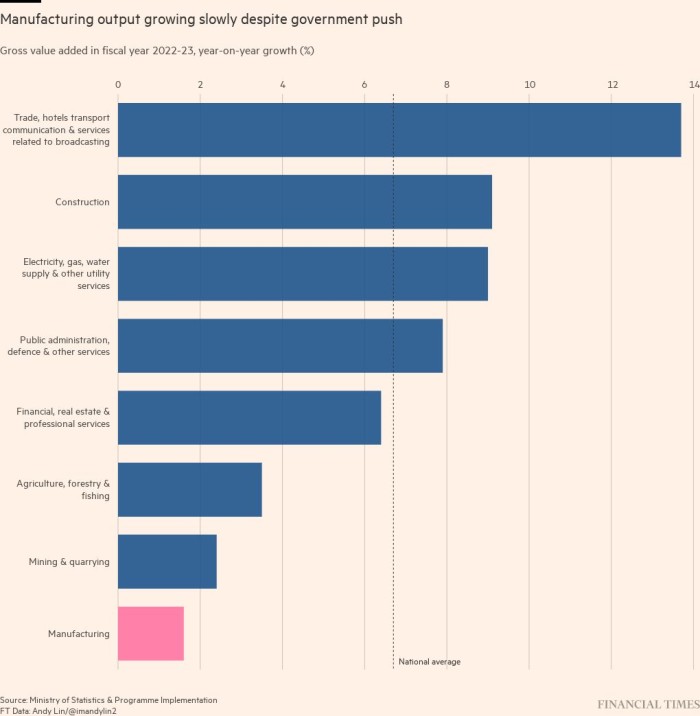

“A lot of the growth in India is driven by finance, insurance, real estate, business process outsourcing, telecoms and IT,” said Amit Basole, professor of economics at Azim Premji University in Bangalore. “These are the high-growth sectors, but they are not job creators.”

Figuring out how to achieve greater job growth, particularly for young people, will be essential if India is to capitalise on a demographic and geopolitical dividend. The country has a young population that is set to surpass China’s this year as the world’s largest. More companies are looking to redirect supply chains and sales away from reliance on Chinese suppliers and consumers.

India’s government and states such as Karnataka, of which Bangalore is the capital, are pledging billions of dollars of incentives to attract investors in manufacturing industries such as electronics and advanced battery production as part of the Modi government’s “Make in India” drive.

The state also recently loosened labour laws to emulate working practices in China following lobbying by companies including Apple and its manufacturing partner Foxconn, which plans to produce iPhones in Karnataka.

However, manufacturing output is growing more slowly than other sectors, making it unlikely to soon emerge as a leading generator of jobs. The sector employs only about 35mn, while IT accounts for a scant 2mn out of India’s formal workforce of about 410mn, according to the CMIE’s latest household survey from January to February 2023.

According to a senior official in Karnataka, highly skilled applicants with university degrees are applying to work as police constables.

The Modi government has shown signs of being attuned to the issue. In October, the prime minister presided over a rozgar mela, or an employment drive, where he handed over appointment letters for 75,000 young people, meant to showcase his government’s commitment to creating jobs and “skilling India’s youth for a brighter future”.

But some opposition figures derided the gesture, with the Congress party president Mallikarjun Kharge saying the appointments were “just too little”. Another politician called the fair “a cruel joke on unemployed youths”.

Rahul Gandhi, the scion of the family behind the Congress party, has signalled that he intends to make unemployment a point of attack for the upcoming election, in which Modi is on track to win a third term.

“The real problem is the unemployment problem, and that’s generating a lot of anger and a lot of fear,” Gandhi said in a question-and-answer session at Chatham House in London last month.

“I don’t believe that a country like India can employ all its people with services,” he added.

Ashoka Mody, an economist at Princeton University, invoked the word “timepass”, an Indian slang term meaning to pass time unproductively, to explain another phenomenon plaguing the jobs market: underemployment of people in work not befitting their skills.

“There are hundreds of millions of young Indians who are doing timepass,” said Mody, author of India is Broken, a new book critiquing the economic policies of successive Indian governments since independence. “Many of them are doing so after multiple degrees and colleges.”

Dildar Sekh, 21, migrated to Bangalore after completing a high school course in computer programming in Kolkata.

After losing out in the intense competition for a government job, he ended up working at Bangalore’s airport with a ground handling company that assists passengers in wheelchairs, for which he is paid about Rs13,000 ($159) per month.

“The work is good, but the salary is not good,” said Sekh, who dreams of saving enough money to buy an iPhone and treat his parents to a helicopter ride.

“There is no good place for young people,” he added. “The people who have money and connections are able to survive; the rest of us have to keep working and then die.”

Additional reporting by Andy Lin in Hong Kong and Jyotsna Singh in New Delhi