“It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it…” – Upton Sinclair

Since the financial crisis, we have seen repeated attempts at attacking indexing all of which have failed — both legislatively and in terms of investors voting with their dollars. Recent attempts – see this, this, this, and this – have similarly failed to persuade investors of the evils of indexing.

I shouldn’t be surprised by the continuous gaslighting by the anti-indexing community, but I am. Sinclair had a clear bead on the financial industry, especially the high-cost, active-investing side of it, even though he was writing about the meatpacking industry.

Regardless, I feel compelled to occasionally channel Jack Bogle to remind people why indexing has succeeded. One would think with Vanguard approaching $8 trillion and BlackRock near $10 trillion, it would be self-evident as to why this has become an investor favorite. Alas, the war against misinformation is never-ending series of skirmishes.

To understand why indexing should be a core part of your investment strategy, consider these five issues:

Costs: Investors can own most broad indexes from the S&P 500 to the MSCI Global for a few basis points. Active management is no longer as crazy pricey as it once was (e.g., 200 basis points); it has come down in cost to the 50 to 100 bps neighborhood. Regardless, those fees compounded over decades will transfer anywhere from 20 to 30% (or more) of the total account value from you to the fund manager. This is to say nothing of the 2 & 20 cost structure of alternatives.

The logic is unassailable: Costs matter, and high costs matter a lot.

Hence, the people making various claims (absurd or otherwise) against indexing always seemed to overlook this simple issue. Somehow indexing is riskier than buying a single stock, or it can lead to industrial conspiracy to fix prices driven by the indexers (?!?), or the perennial favorite, “Just wait until the next downturn, you will clearly see the value of (higher cost) active management.” Yet each time, that value fails to manifest itself.

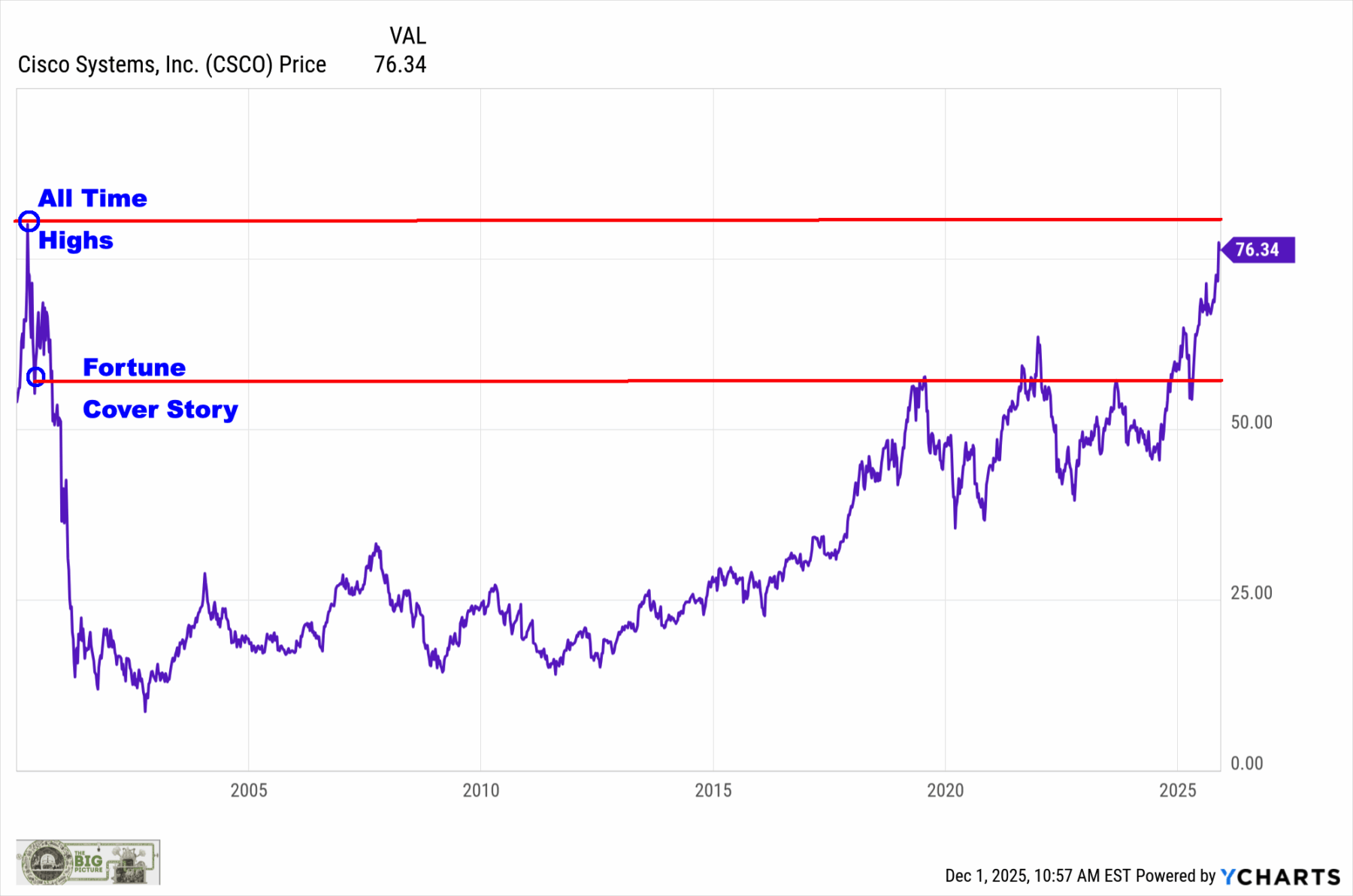

Stock Selection: Throughout the history of investing, there have been a group of savants who have proven themselves to be brilliant stock pickers: Peter Lynch, Warren Buffett, Benjamin Graham, John Templeton, Thomas Rowe Price Jr., John Neff, Julian Robertson, and Will Danoff round out the list. Their numbers are few – they are the exception that proves the rule.

The challenge in selecting stocks is that the vast majority of them don’t move the needle. Academic research has shown most stocks don’t really matter; the typical stock may be up a bit or down a bit, while more than a few disasters crash and burn. But the big drivers of market returns are the 1.3% of publicly traded companies that put up those giant performance numbers over an extended period of time.

The odds are worse than 50 to 1 against you picking those big winners; and even worse that you pick only those big winners.

Market-cap-weighted indexing, on the other hand, guarantees not only that you will own them but that as these companies get bigger, you will own more of them. Over time, this has proven to be a very tough formula to beat. Add in the higher costs and it proves to be nearly impossible.

Behavior: When investors index they make a series of decisions: How much equity, how much bonds, how globally diversified, how much will I add each paycheck, and how often do I rebalance? But that’s pretty much it and once you get past those five initial decisions, it’s pretty much set and forget for the next few decades.

Therein lay the genius the true genius of indexing: everything else from stock selection to market timing to sell decisions invariably involves cognitive errors so common to human investing decision-making. Avoid behavioral problems and eliminate the vast majority of mistakes and once again you are guaranteed to do better than almost everybody else.

Average Becomes Outperformance: Howard Marks made this very astute observation: finish in the top half of managers by avoiding the typical errors and over time you’ll work your way into the top decile of long-term returns.

The counter-intuitive reason: It’s not the excellent years that lead to this outcome but rather, the avoidance of disastrous down years. Simply avoiding big errors leads to enormous wins. Take what the market gives you year after year while others occasionally beat but often fail to do so and occasionally blow up; over time, merely Beta bubbles to the top of the performance ranks.

It’s not that you need to be smart but rather, you just have to not be stupid.

Simplicity: All other things being equal, simplicity beats complexity every time. A portfolio of passive low-cost indexes should make up the core of your holdings. If you want to do something more complicated, you need a compelling reason.

There are lots of things we do at RWM that go beyond our core philosophy of indexing, but only when the upsides outweigh the downsides significantly. Direct indexing for clients who need to offset large capital gains; Goaltender to manage emotional errors; Milestone rewards to incentivize good behavior through lower fees. Each of these has a degree of complexity but its greatly outweighed by the positive results they create.

Bottom line: Indexing has moved from an abstract theoretical approach to investing widely ignored by investors to a key methodology for millions of people, despite – or perhaps because of – the disdain Wall Street has shown.

Previously:

Winner Takes All Applies to Stocks, Too (August 1, 2019)

Wasn’t Passive Supposed to Blow Up During the Next Crash? (March 19, 2020)

My Investing Philosophy in a Nutshell (May 4, 2022)

Transcript: Jack Bogle, Vanguard (January 20, 2019)

Active vs Passive Management

Vanguard Group

See also:

Index Investing is Misunderstood (June 18, 2023)