Roman Didkivskyi/iStock via Getty Images

In his first change in monetary policy since being appointed Governor of the Bank of Japan in April, Kazuo Ueda surprised the financial markets with a “tweak” to the BOJ’s seven-year-old Yield Curve Control (YCC) Policy following last Friday’s Monetary Policy Meeting.

The “tweak” essentially widened the band around the BOJ’s target yield of 0.0% for 10-year Japanese government bonds (JGBs) from +/- 50 basis points to +/- 100 basis points.

In an 8-1 vote, the Policy Board of the BOJ decided to continue allowing 10-year JGB yields to fluctuate in the range of +/- 50 basis points around their target, but it will conduct YCC with more flexibility, as the upper and lower limits to the range are now “references” instead of “rigid limits.”

The BOJ will offer to purchase 10-year JGBs at +/- 1.0%, the new band, on every business day through fixed rate purchase operations.

In a unanimous vote, the BOJ agreed to keep the short-term policy rate at -0.1% and to purchase JGBs in an unlimited amount to keep the 10-year JGB yield within the new range.

If this seems confusing, it is.

The new YCC policy is a range with five rates:

Upper Band Yield =1.0%

Upper Band Reference Yield = 0.50%

Target Yield = 0.0%

Lower Band Reference Yield = -0.50%

Lower Band Yield = -1.0%

Why BOJ “Tweaked” YCC

The BOJ wants a price stability target of 2% accompanied by wage increases, which it has not seen yet. They appear to believe they must patiently continue with monetary easing under Quantitative and Qualitative Easing (QQE) and YCC. Because of the uncertainty of economic activity and prices, the BOJ believes “it is appropriate… to enhance the sustainability of monetary easing under the current framework by conducting yield curve control with greater flexibility and nimbly responding to both upside and downside risks to Japan’s economic activity and prices.”

Ueda has insisted that the recent move is not a precursor to policy normalization.

Perhaps it should be.

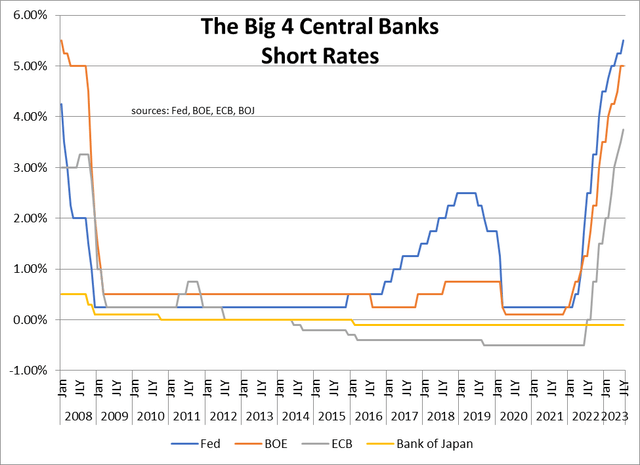

BOJ Only Major Central Bank Still Easing Monetary Policy

Like the economies of the other major developed countries, inflation in Japan spiked above the 2% target beginning last year. But unlike the other countries which began reversing their QE policies of the prior decade by raising interest rates aggressively and implementing Quantitative Tightening (QT,) the BOJ is determined to maintain an easy monetary policy

This policy decision is controversial, as the yield gap between the BOJ and the other major central banks has widened dramatically.

BOJ, ECB, BOE and Federal Reserve

Over the past eighteen months, the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, and the European Central Bank have raised rates by 525 basis points, 475 basis points, and 425 basis points, respectively, to fight inflation. By maintaining its easy, -0.1% short-term policy rate, the wide yield gap has put heavy downward pressure on the yen. It also has led to substantial foreign investment to achieve higher yields.

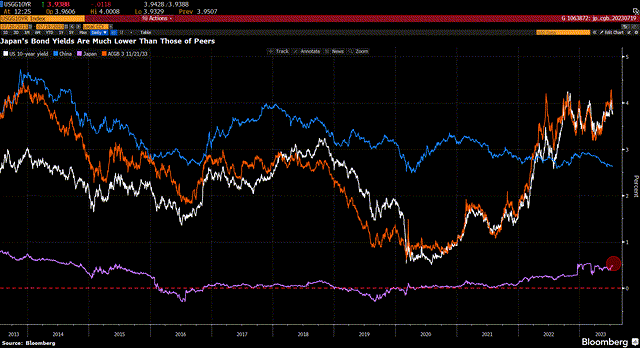

The below chart shows the yield differentials between 10-year JGB yields and those of some of its peers.

10-year JGB Yield and Peer Bond Yields

Bloomberg

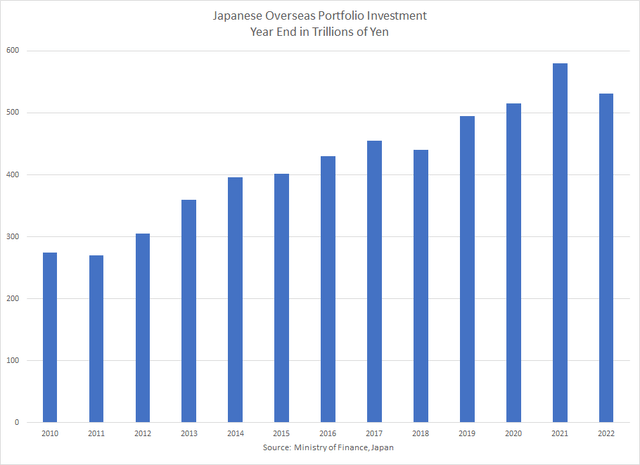

According to the Ministry of Finance, overseas investment reached 531 trillion yen at the year-end 2022. Because of the low rates in Japan, outflow of funds accelerated and foreign investment increased by 70% over the past ten years.

Ministry of Finance, Japan

Inflation

The main driver of global monetary policy tightening has been the surge in inflation as a result of the easy money policies of the past. Japan has not been immune from this inflation resurgence.

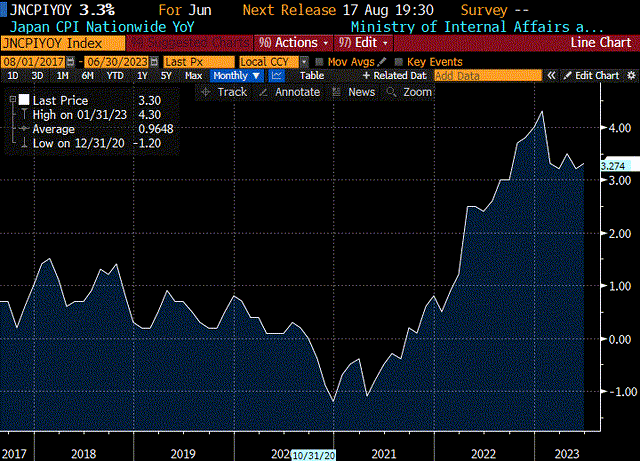

The most recent headline CPI for June came in at 3.3% y/y. While this is down from the January peak of 4.3% y/y, it is still above the target rate of 2.0%. CPI has exceeded the target for the past 15 months. Wages have also started increasing after years of stagnation.

Bloomberg

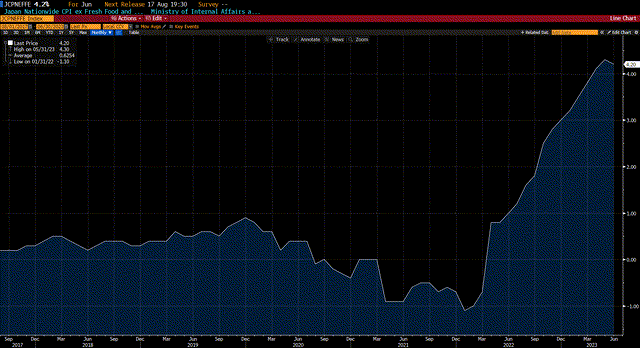

Scrutinizing the numbers more thoroughly, the closely watched Core Core CPI continues to rise. The “Core Core” rate measures CPI excluding the volatile components of fresh food and energy. This rate climbed to 4.2% y/y in June down slightly from May’s 4.3% y/y, the highest level in over 40 years

Japan Core Core CPI y/y

Bloomberg

The surge in core inflation is one of the main reasons why BOJ tweaked their YCC policy.

In the recently released statement the BOJ upgraded their core inflation forecast for this year from 1.8% to 2.5%. The forecast for 2024 was inched lower to 1.9% from 2.0%.

History of Yield Curve Control

When YCC was implemented in 2016, Japan was in a deflationary period and 0.0% long interest rates were appropriate. Recently, however, inflation has increased significantly and there has been substantial pressure to alter the policy.

Part of the YCC policy was that the BOJ committed to buy as many JGBs as necessary to keep the 10-year yield near zero.

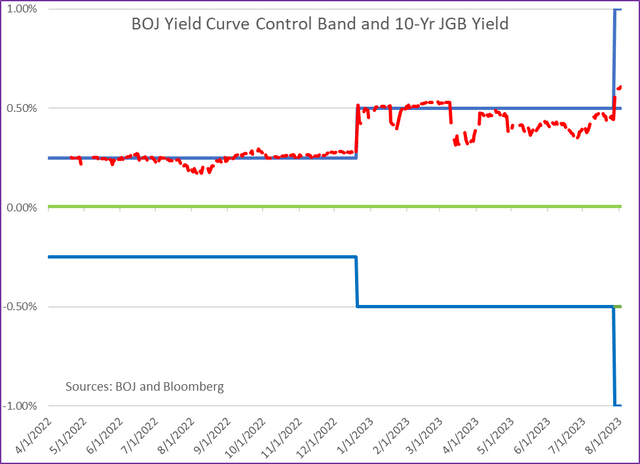

As pressure mounted the BOJ modified their policy. First, in 2018 they created a band of +/- 20 basis points around the 0.0% target on the 10-year yield. Then in 2021 the band was widened to +/- 25 basis points. In a surprise move in December 2022 the band was again adjusted by doubling it to +/- 50 basis points.

BOJ and Bloomberg

As can be seen in the chart above, at each change market speculators pushed the yield to the top end of the band.

With last Friday’s surprise move, yields also jumped. As of 8/1/23 the 10-year yield is at 0.61%. Ueda does not expect the 1.0% yield to be reached now, but it was set as a precaution. The feeling was better to set it at a high level now, so it wouldn’t have to be changed again in the near future.

The Yield Curve Control Policy Is Out Of Control

The BOJ’s description of their new policy appears to be just a minor technical adjustment, as they state to offer more “flexibility.”

An objective analysis of the above chart, however, tells a different story. YCC is supposed to control rates around the target level of 0.0%, with symmetrical movements around the band. This made sense when it was instituted and yields were trading around 0.0%.

For the past 18 months, though, the symmetry is non-existent. In this inflationary environment, the target rate is just a policy statement. Of the five target rates mentioned in the initial statement, only one is truly relevant. That rate is the top end of the band yield.

Many speculators have been anticipating the demise of YCC, and have been trying to force the issue. This has caused by BOJ to battle with them and step up to their commitment to intercede through unlimited JGB purchases to protect the band.

A major problem with the yield curve control policy is that it doesn’t control the entire yield curve. It only controls one point on the curve, that of the 10-year JGB.

Consequently, yields at other maturities move more freely. With upward pressure across the entire yield curve, it attained an artificial shape with a kink at the suppressed 10-year maturity.

The below chart shows the entire yield curve at two points in time. The yellow line represents the yield curve at 3/31/23, which is the BOJ’s fiscal year-end, and is when Ueda assumed his new position. This curve shows the artificial shape with a kink at the 10-year maturity.

Japan JGB Yield Curves

Bloomberg

The green line shows the yield curve as of 8/1/23, following the YCC “tweak” on 7/28/23. One noticeable difference is that the curve smoothed out, into a more normal shape. The second difference, of course, is that yields increased dramatically across the curve with the new policy. The 10-year yield increased the second most, rising by 27 basis points. The 30-year, a less frequently traded maturity, rose the most by 30 basis points.

Liquidity

Liquidity was another reason for the BOJ’s surprise YCC “tweak.” Liquidity, or lack thereof, has been a problem for quite some time. The reason for this is that the BOJ owns so much debt and the tradeable market float is limited.

As of Fiscal Year End, March 31, 2023, the BOJ owned more than 53% of the entire JGB market, a record high. BOJ has owned more that 50% of the market for three straight quarters. When YCC was instituted, the BOJ only held 11% of the JGB market.

BOJ Owned Share of JGB Market

Bloomberg

As other central banks are currently shrinking their balance sheets with Quantitative Tightening, the BOJ is moving in the opposite direction by greatly expanding their balance sheet. During the past year the BOJ’s JGB holdings increased by 10.5%

The BOJ’s stated goal was to buy up to 7.3 trillion yen of JGBs per month in 2022. They generally followed this path until June 2022 when speculators stepped in.

As other central banks were tightening and interest rates around the world were rising, investors started betting that the BOJ would be forced to alter, or abandon, its interest rate target. They began shorting JGBs. To defend the band, the BOJ adhered to their commitment to buy whatever was necessary to maintain their target, and wound up purchasing a then record 16.1 trillion yen of JGBs for the month. This was more than double their stated goal. Volatility calmed for a bit and they resumed their scheduled JGB purchases.

BOJ

The speculators returned in September with their bets against the BOJ, and the BOJ purchased 11.9 trillion yen of JGBs in September, and another 11.3 billion yen of JGBs in October. The band held.

But the pressure was growing on BOJ. They couldn’t continue buying JGBs at this pace. This is why in December there was a surprise announcement and the band was expanded from +/- 25 basis points to +/- 50 basis points. The BOJ said the move was a tweaking and was aimed at smoothing out the distortions of the yield curve, and not a policy move or abandonment of YCC.

The yield on the 10-year JGB immediately spiked to near the top of the new band and the BOJ was forced to respond with more purchases. In December they bought a record 16.6 trillion yen of JGBs and then in January they had to buy a new record 22.8 trillion yen of JGBs.

For Fiscal Year End 3/31/23 the BOJ bought a record 136 trillion yen of JGBs. This was almost double the 70 million yen of JGBs purchased in FYE 3/31/22.

The BOJ has had in place a Securities Lending Facility (SLF) for quite some time as a means to create more liquidity in the market due to their heavy ownership of JGB’s.

One unusual twist to this situation is that the BOJ was actually lending JGBs that they owned to speculators so they could short them. These short sellers who bet on a change in monetary policy are making the BOJ’s YCC more difficult by putting upward pressure on yields.

A further complication of the situation is that due to heavy purchases by the BOJ from speculators who are borrowing the BOJ’s bonds utilizing the SLF, the BOJ owned more than 100% of three of the current benchmark 10-year JGBs.

According to Oxford Economics, after the assault on higher yields by speculators following BOJs December band expansion and subsequent purchases by BOJ to defend the band, the BOJ had absorbed all the liquidity of on-the-run-10-year JGBs from the market.

Oxford Economics

In late February the BOJ implemented a plan to reduce speculation by changing the terms of their SLF by raising fees dramatically. The cost to borrow securities was quadrupled from 25 basis points to 100 basis points.

With the BOJ owning so much of the 10-year JGBs, an odd situation was created in March, soon after the new SLF policies, where the shorts were squeezed, causing the 10-year yield to plunge from 0.53% to 0.28% over six trading days.

There is one sign that the increase in fees is having a positive effect. According to the Bloomberg JGB liquidity index, there has been some improvement in market liquidity.

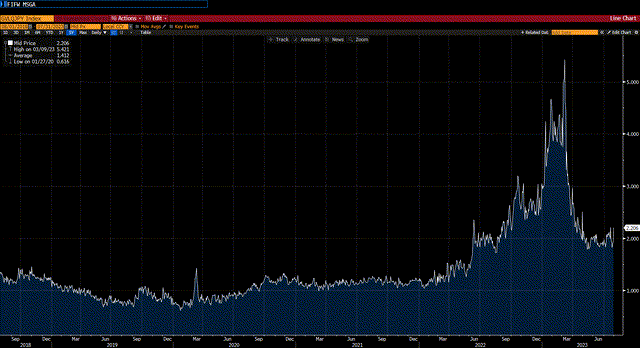

JGB Liquidity Index

Bloomberg

This index measures the liquidity of the JGB market. The index displays the average yield error to relative value. When liquidity is favorable yield errors are small. Under stressed conditions, dislocations from fair value can remain, resulting in larger yield errors.

The chart shows how liquidity began deteriorating in June 2022, took another spike higher in September 2022, spiked in December 2022, rose again in January 2023, and finally peaked in February 2023 after the new SLF guidelines went into effect. Since then, there has been significant improvement.

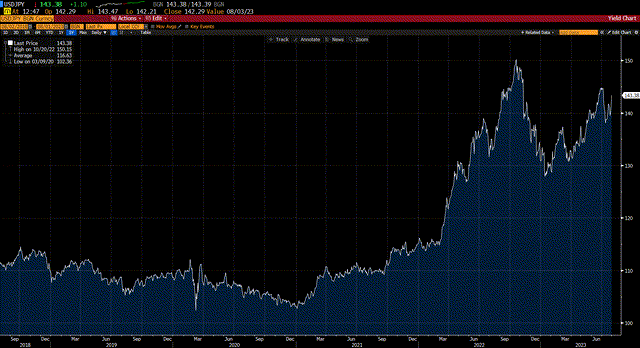

Yen

When yield differentials widened relative to other developed countries as they tightened by raising rates, the exchange value of the yen was crushed. The yen spiked to 153 versus the dollar by late fall 2022, a 25% decline from the beginning of the year. It had a quick 20% recover, but then started weakening again. Once it broke above 140, close to the lows, the BOJ again became concerned with its weakness. This was a contributing factor in their YCC tweaking. The policy move, however, does not appear to have helped.

Yen Exchange Rate

Bloomberg

Unrealized Bond Losses

Most of the above discussion supports that the BOJ should change, or abandon, their easy money policies and tighten to fight inflation like the other central banks of the developed world. This means normalizing policy through the elimination of YCC and eliminating their negative short-term policy rate.

Such a move though, would exacerbate another problem facing the BOJ, which they share with the other major central banks.

The BOJ has a massive bond portfolio that is carried on their balance sheet at amortized cost. Virtually all of these securities were purchased when rates were close to 0.0%. Tightening that would raise interest rates and would create a huge unrealized loss on their bond portfolio.

For FYE 3/31/23 the BOJ reported an unrealized loss on JGB’s for the first time in 17 years amid rising bond yields. The paper loss was 157 billion yen, versus a paper profit of 4.373 trillion yen the prior year. This is a 4.53 trillion yen decline in value over the year as the 10-yr JGB increased by 12 basis points for the year. Since FYE 3/31/23 the 10-yr JGB has increased in yield by 27 basis points, so the unrealized portfolio loss year to date could approximate 9 trillion yen. This is more than double the BOJ’s capital. Further increases in yields will only intensify the problem.

In recent testimony BOJ Deputy Governor Amamiya stated that if the entire yield curve shifted upward by 100 basis points the BOJ’s unrealized loss would increase to 29 trillion yen.

Summary

The recent monetary policy move by BOJ Governor Ueda was presented as just a “tweaking” but it was so much more.

The Bank of Japan is the last man standing in the world of central banks clinging to easy money with a Negative Interest Rate Policy, despite above target inflation for 15 months. I believe their Yield Curve Control Policy is one in name only, as the yield curve is not completely under their control in my view.

They appear to be following the market instead of leading. They should normalize policy, now.