There’s a Chinese proverb that holds it is better to plan one’s means of retreat than 36 different ways to win the battle.

It’s an axiom that has cropped up on Tokyo trading floors this autumn, after Japan lavished a record $62bn to fight the yen’s collapse below a three-decade low, in as many as four separate interventions since September.

It’s only one front in its war against global market forces. By the end of June, after months fighting to control the yield curve, the Bank of Japan had raised its holdings of Japanese government bonds (JGBs) to over half a quadrillion yen ($3.6tn). Last week, to fight the negative impact of inflation, the government unveiled a $200bn stimulus package.

There is mounting fear, however, that an orderly retreat may be impossible. Instead the BoJ is betting everything on yet another strategy aimed at winning the battle. It is making a giant gamble that a royal flush of national and international outcomes will solve its most pressing problems: sizeable wage increases by Japanese companies, the onset of “good” inflation, visible stability in the yen, a soft US recession and an interest rate pivot by the Federal Reserve.

But at the same time, the radars of investors around the world are beeping noisily with signs of a potentially explosive Japan crisis.

In an October blog post that went viral, George Saravelos, a Deutsche Bank strategist, described Japan’s yield curve control policy — curbing the short and long-term interest rates on Japanese government bonds — as “for all intents and purposes, already broken”.

The yield curve not only demonstrated the scale of policy distortion but its likely limits, too, he wrote. The BoJ is reaching “near-full ownership” of the three bond yields it has targeted, meaning “the time is soon approaching where these bonds will stop trading in their entirety and the market will simply cease to exist”, he wrote.

But the JGB market is just one symptom of a larger distortion, analysts and traders say. Too much of the current Japanese policy mix and its secondary market effects seem unsustainable, says the head of one global fund, and waiting for the outcome of Japan’s bet could become unbearable.

Despite the interventions, Japan’s currency continues to test new lows around ¥150 against the dollar. The widening interest rate differential between Japan and the US means few are yet confident where the yen will find a natural floor. With Japan the only major economy still running a zero-interest-rate policy, the BoJ is looking ever more isolated.

“There’s a logic and a strategy behind what the BoJ is doing, but it’s a risky one. Everything could work out reasonably well as long as we are in a scenario next year where there’s clear evidence of US inflation coming down,” says Derek Halpenny, head of research for global markets at Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group.

“The big risk is if that doesn’t happen. They want to relax yield curve control in a world where global bond yields are coming down. If they’re not, then the longer they leave it, the more disorderly the exit,” he adds.

Mansoor Mohi-uddin, chief economist at Bank of Singapore, says the closest analogy to understand the potential consequences would be the Swiss National Bank’s abrupt removal of the ceiling on the Swiss franc in 2015, which led to a large jump in the currency and left European equity markets reeling.

“But Switzerland is a small economy compared to Japan,” Mohi-uddin says. A disorderly exit by the BoJ would cause a huge surge in 10-year Japanese government bond yields, causing “major disruptions” for bondholders, from domestic pension funds to central bank reserve managers overseas. The Nikkei would plunge, he adds, with the ripples felt across global stock markets.

The expectation of inflation

To market watchers, the BoJ’s determination to carry on with its experiment appears dangerous in a world where countries are scrambling to keep inflation at bay.

But for Haruhiko Kuroda, this is exactly the moment he had been waiting for since he became Bank of Japan governor in March 2013 vowing to do “whatever it takes” to end the country’s bouts of mild yet corrosive deflation.

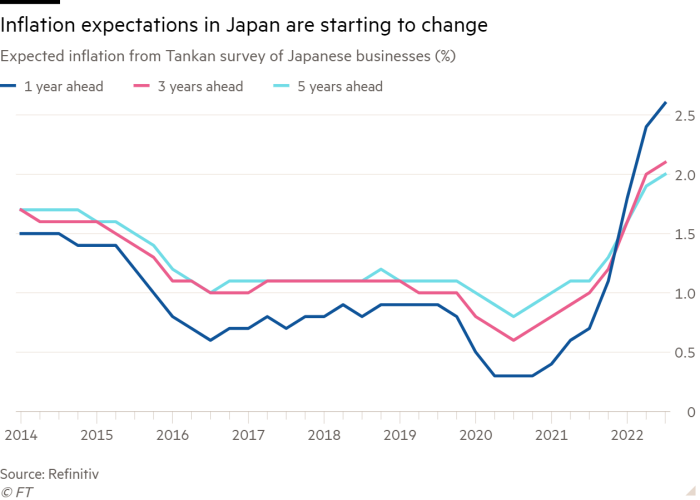

Helped by a global surge in commodity prices caused by the war in Ukraine, prices of goods in Japan are rising with inflation hitting 3 per cent, surpassing the BoJ’s target of 2 per cent. More importantly, both companies and households now expect prices to increase over the next few years, after almost two decades of believing that prices could only go down.

The enduring assumption that prices in Japan will not change is finally crumbling, says Kentaro Koyama, Deutsche Bank’s chief Japan economist in Tokyo. “To take advantage of this precious opportunity, monetary policy needs to encourage price change, and this is why the BoJ’s bias toward maintaining its current monetary policy is reasonable,” he says, in a striking change of tone from his colleague Saravelos.

According to the latest consumer confidence survey released by Japan’s cabinet office this week, 63 per cent of those polled said they expected prices to rise 5 per cent or more over the coming year.

The BoJ’s Tankan, a closely watched survey on business sentiment, also showed that in September, Japanese companies expected an inflation rate of 2 per cent within five years, the highest level since it began polling such expectations in 2014.

Creating the presumption of inflation is critical in Japan, a country that has struggled to dislodge the expectations set by 15 years of on-and-off deflation between 1998 and 2013. This mindset has also posed the biggest hurdle for rising prices to be reflected in employee earnings.

The worry for the BoJ is not a wage spiral that could result in a more prolonged period of high inflation, as it is in the US and Europe, but the opposite: the lack of strong wage growth that would shield the economy from falling back into a deflationary spiral.

A weaker yen may also help kindle wage growth. Even though benefits have waned as companies have shifted manufacturing abroad, a softer currency still increases corporate profits made overseas when they are repatriated and the hope is that robust earnings will make it easier for businesses to raise wages.

“To get rid of the deflationary mindset, they were prepared to see a weaker currency. What they wanted badly was for this inflation rate of 3 per cent to be translated into higher wages. This is the most important thing in Japan,” says a former senior BoJ official.

Wage growth needed

The ace in the hole for the BoJ, say analysts, may not be a potential pivot by the Fed, but the “shunto” wage negotiations in the spring.

These annual talks between unions and employers have for many years delivered a build-up of hope followed by a collective slouch of disappointment among workers across the country.

In a sign of changing times, the Japanese Trade Union Confederation (Rengo) is seeking a 5 per cent year-on-year increase in wages — 3 per cent in terms of base pay — during the spring negotiations, the highest since 1995.

If such a serious wage hike is in prospect, it would also coincide with the change in BoJ governorship when Kuroda’s term expires in April.

If a trend for a steady wage rise can be confirmed, that might give the next BoJ governor confidence to consider reining in the quantitative and qualitative monetary easing (QQE) programme.

Kuroda has argued that any tightening would be premature with Japan’s core inflation expected to fall below its 2 per cent target by next year, but the BoJ’s current forecast does not take into account potential wage hikes by companies in spring.

“Strong wage growth is seen as the ultimate ‘amulet’ against Japan slipping back into disinflation,” argues David Bowers, co-founder of Absolute Strategy Research. “If [the talks] succeed, then it may be that the Bank of Japan — under Kuroda’s successor — can start to pivot away from its QQE narrative, with implications for the yen and for bond yields not just in Japan but around the world.”

Still, economists are divided on how much companies would be willing to increase employees’ pay after resisting for so long. While some are cautiously raising the price of their products, others are still afraid consumers will balk at higher prices, creating a chicken-and-egg problem for corporate Japan.

“If companies generate profits and raise wages, demand might pick up. But which comes first? Companies cannot raise wages if they are not making money, while consumers cannot buy goods at higher prices if their wages are not going up, ” says Masahiro Okafuji, chief executive of Itochu, one of Japan’s big five trading houses.

“We can’t easily criticise the BoJ since companies will suffer as well if a wrong decision is made,” he adds.

Time to buy Japan?

The 28 per cent descent of the yen against the dollar so far this year has reignited the broader question of how investable Japanese markets are.

Ten years ago, the economic and regulatory reforms that took place under “Abenomics” pushed Tokyo-listed equities, as measured by the Topix index, into a multiyear rally and a near 100 per cent rise in value. But more recently, Japanese equities have to some extent become another highly visible symptom of where BoJ policy has far outstripped its original plan.

In the two-and-a-half years that followed the arrival of Shinzo Abe as prime minister in 2012 and the appointment of Kuroda as BoJ governor, foreign investors bought a net ¥25tn of Japanese shares.

In the years between 2015 and today, they have reversed that completely, selling ¥25.6tn. Over the past 10 years, the BoJ has been a net buyer of ¥36tn, via its ETF-purchasing programme.

The circumstances might seem ripe for another rally. Japanese companies look relatively stable and, because of the yen, very cheap. In theory, a robust influx of foreign stock-buying would shore up the yen and create the kind of natural upward pressure that would save the Japanese authorities from digging ever deeper into the national store of US Treasuries to artificially support the currency.

In reality, the yen is locked in a volatile trading pattern dictated by massive outflows by Japanese companies and asset managers. While that is causing instability, foreign investors may still decline to “buy Japan”.

Bruce Kirk, head equity strategist at Goldman Sachs in Tokyo, says currency stability is essential for investment committees to look at Japan again. “There is a lot of interest from foreign investors in Japan, but what is holding them back is that they feel they don’t yet know how much further the yen could fall and whether the 150 level is the answer or whether it could fall further towards 175 or 200.”

The Japanese authorities may be muddying the situation, say analysts, in how they are responding to the recent volatility of the yen. Repeated references by Japan’s finance minister Shunichi Suzuki and other officials to market speculators heavily overstate the role of hedge funds and other leveraged investors.

Shusuke Yamada, chief Japan forex and equity strategist at Bank of America, says that it was “real money” driving the yen’s fall this year: corporate Japan and domestic Japanese asset managers responding to the rate differential, Japan’s trade deficit and foreign direct investment deficit.

Unlike the period immediately before the 2008 global financial crisis, where speculators at home and abroad would borrow yen and sell it to buy higher-yielding assets in what was known as the “carry trade”, there is less excitement around such investments now, says Yamada.

All the central bank can do now is wait out the storm, he adds. “The BoJ is trying to buy time, hoping that the US rates peak out and smoothing the moves where they can,” he adds. “How this will play out ultimately depends on the US side.”

The exit ramp

Few economists expect Kuroda to change course before his term expires next year. But when Japan eventually (and, some say, inevitably) does, it will be fraught with risk.

Experts agree any hint of normalisation from the BoJ will require intricate communication with markets to avoid the risk of misinterpretation. “The BoJ will need to come up with a basic plan beforehand so that the market can expect what will be coming,” the former BoJ official says.

Kuroda said as much at a news conference last week. Though “we are not thinking of a rate hike or an exit anytime soon . . . when the 2 per cent [inflation] target becomes reachable, the policy board will need to discuss the exit strategy and it will be important to properly communicate with the market,” he said.

Masamichi Adachi, chief economist at UBS in Tokyo, says the BoJ is likely to make a public assessment of the effects of its monetary policy during 2023 to signal an adjustment is looming. It did something similar before bringing in yield curve control, he says.

A first step might be to revise the BoJ’s forward guidance and widen the 0.25 per cent target on 10-year JGBs, Adachi adds. “We could call this process a beginning of policy normalisation for improving bond market function, allowing a smooth start without difficult pressure from markets.”

On Wednesday, Kuroda dropped his biggest hint yet that a pivot point might be approaching. “If the achievement of our 2 per cent inflation target that is accompanied by wage hikes comes into sight, a review of the monetary policy will of course become necessary,” he told parliament.

But any tweak that is perceived to be too fast or beyond expectations could cause rapid repercussions across markets.

When yields in the UK spiked in the wake of September’s “mini” Budget, the Bank of England had to step in to support pension schemes facing sudden, unexpected liquidity issues. If the Japanese central bank were forced into a similar action with bondholders, the scale of intervention would need to be far, far larger — with much higher risk of global contagion.

Little wonder then that within the BoJ and the Japanese government, the crisis in the UK gilts market has become a cautionary tale. “It’s become a lesson for markets as well as policymakers that Japan must not become like the UK in terms of the turmoil that it caused,” says Mari Iwashita, chief market economist at Daiwa Securities.

A disorderly exit is not yet on the cards. But Kuroda will be watching the flop carefully, hoping he reaches the end of his term with the strongest hand possible.