How demand shocks propagate by an input-output community: The circumstances of the worldwide monetary disaster and the COVID-19 pandemic

The propagation of shocks by way of input-output linkages amongst companies (i.e. provide chains) has gained consideration amongst economists. The continuing COVID-19 pandemic and up to date geopolitical incidents additional necessitate research on the theme. On this context, latest theoretical evaluation (e.g. Acemoglu et al. 2012) exhibits that microeconomic shocks to hub companies in an input-output community have a big influence on combination output. Moreover, due to the growing availability of firm-level knowledge, latest empirical research straight analyse such firm-level input-output networks and discover propagation phenomena. For instance, Barrot and Sauvagnat (2016) use pure disasters within the US because the supply of unfavorable shocks to companies and study the propagation of those shocks by way of input-output linkages. Boehm et al. (2019) and Carvalho et al. (2021) use the Tohoku earthquake in Japan in 2011 and present that this unfavorable shock propagates to different prospects in unaffected areas.

These earlier research deal with propagation pushed by provide shocks; that’s, shocks propagate ‘downstream’ from provides to prospects. In distinction, ‘upstream’ propagation from prospects to suppliers pushed by demand shocks is never examined within the empirical literature. Two exceptions are Acemoglu et al. (2016) and Kisat and Phan (2020), however their evaluation depends on a sector-level input-output community. To the most effective of our data, there isn’t a empirical examine that straight observes the demand-shock propagation by a firm-level input-output community.

In a latest paper (Arata and Miyakawa 2022), we purpose to fill this hole within the literature utilizing Japanese firm-level input-output knowledge. We deal with demand-shock propagation originating from the sharp drop in exports through the World Disaster and the change in client behaviour through the COVID-19 pandemic. Viewing these occasions as exogenous to Japanese companies, we study how gross sales development charges are affected by the presence or absence of their transacted prospects broken by the unfavorable shocks. We use the heterogeneous remedy impact mannequin developed by Athey et al. (2019) and Wager and Athey (2018), which permits us to analyse how the propagation impact depends upon agency traits, comparable to agency dimension. By specializing in the heterogeneity of the propagation impact, we study the route of the demand-shock propagation by the input-output community.

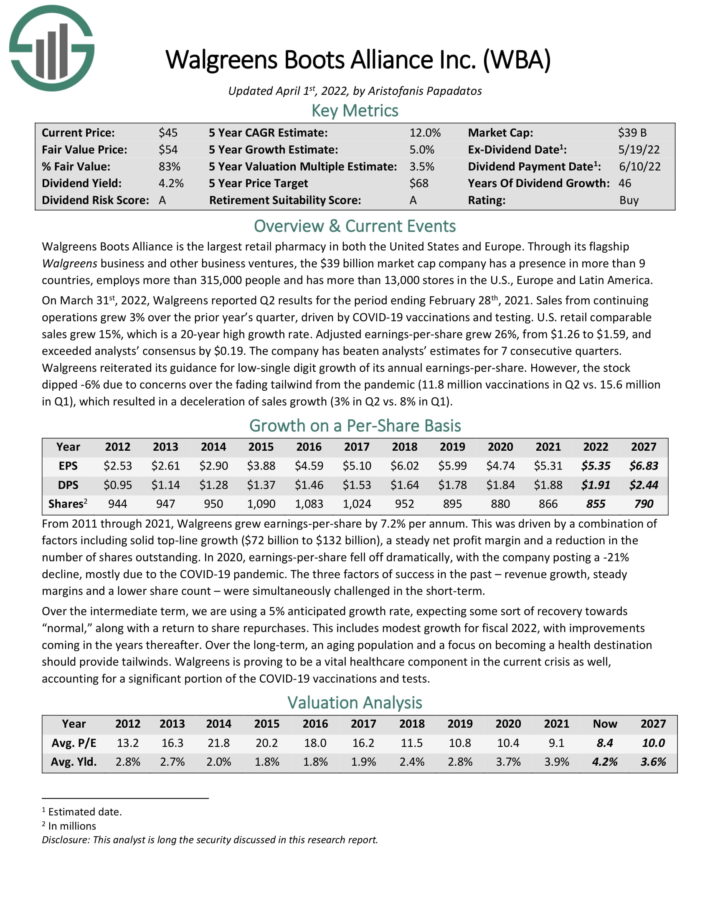

Our evaluation exhibits that through the world monetary disaster, the propagation impact is substantial for big suppliers however not for small suppliers (see Determine 1). That’s, unfavorable shocks to exporting companies should not transmitted to their small suppliers, particularly when the exporting companies are giant. We discover that whereas the exporting companies which might be dealing with the decline in exports cut back inventories, the gross sales development charges of their small suppliers don’t reply to the unfavorable development charges of those exporting companies.

Determine 1 Response of the expansion charges of provider companies’ gross sales to the expansion charges of their buyer companies’ gross sales through the world monetary disaster

Notes: The propagation impact depends upon the log sizes of suppliers and their prospects. Buyer dimension is categorized into 4 teams: small (gross sales ≤ first quantile), middle1 (first quantile ≤ gross sales ≤ median), middle2 (median ≤ gross sales ≤ third quantile), and enormous (gross sales ≥ third quantile). The left panel and proper panel account for the provider companies in manufacturing industries and wholesale & retail industries, respectively.

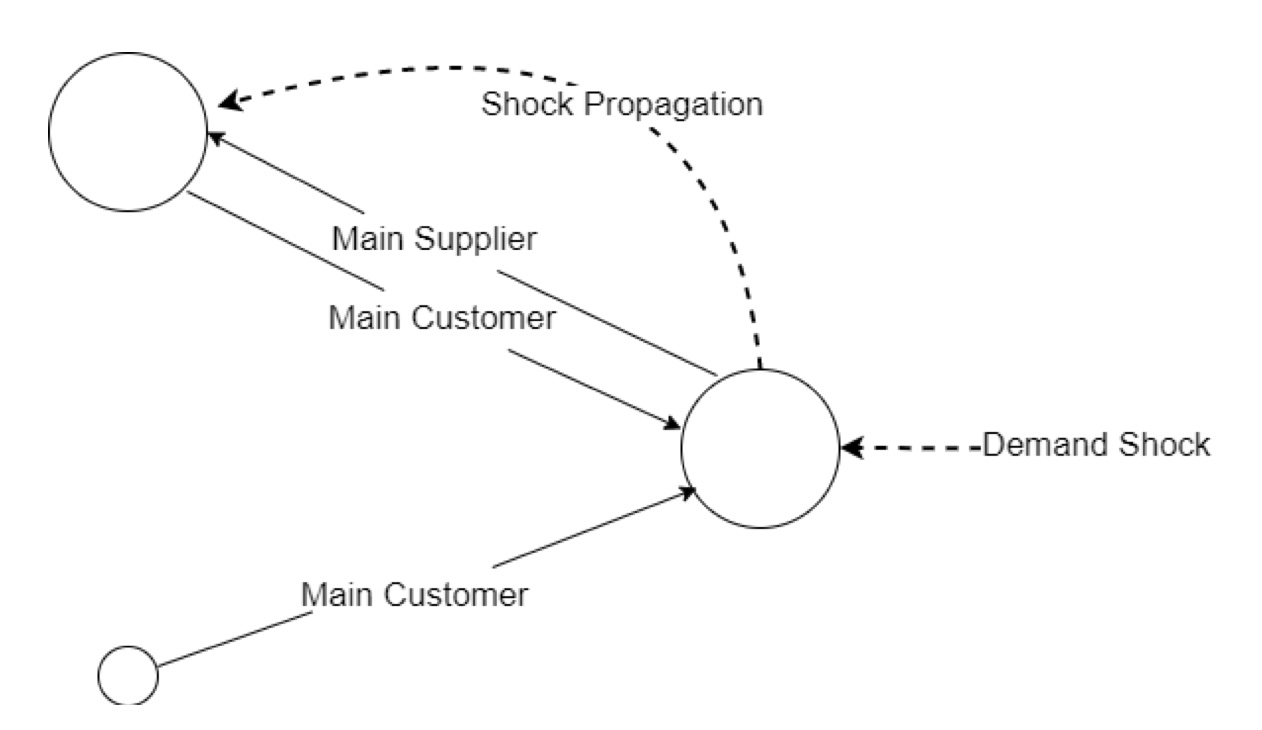

It’s because the propagation impact just isn’t homogenous, and specifically, demand shocks propagate from prospects to suppliers solely when the latter are the principle suppliers (see Determine 2). We discover that even in circumstances the place the purchasers experiencing a big decline in exports are considered by the provider as the principle prospects, the unfavorable shocks should not transmitted to the provider if this provider just isn’t considered by the client as the principle provider. As well as, we discover that giant suppliers are more likely to be chosen as the principle suppliers, particularly by giant prospects. Since most exporting companies and their important suppliers are giant companies, demand-shock propagation primarily happens inside these giant companies through the world monetary disaster.

Determine 2 Route of the demand-shock propagation

Notes: The scale of the circle represents the dimensions of the agency. Demand shocks propagate to suppliers solely when they’re the principle suppliers for the client. Specifically, the propagation of demand shocks doesn’t happen between giant prospects and small suppliers.

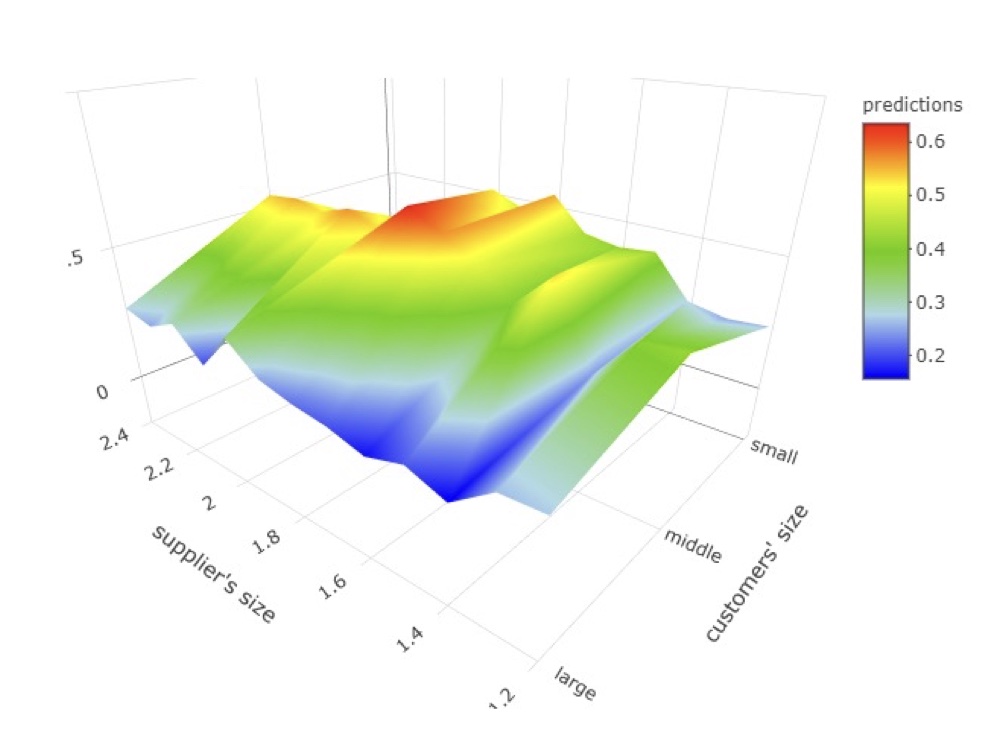

The discovering of the heterogeneity of the propagation impact raises one other query. If demand shocks hit companies with small important suppliers, do the unfavorable shocks propagate to the small suppliers? That is what occurred through the COVID-19 pandemic (see Determine 3). Most companies within the COVID-affected sectors, comparable to eating places and resorts, are small and their important suppliers are additionally small. We discover that there isn’t a vital heterogeneity of the propagation impact throughout the dimensions of suppliers. That’s, unfavorable demand shocks propagate even to small suppliers. This result’s in step with our interpretation that propagation happens solely by the linkages which might be related to each suppliers and prospects.

Determine 3 Responses of the expansion charges of provider companies’ gross sales to the expansion charges of their buyer companies’ gross sales through the COVID-19 pandemic

Word: Buyer dimension is categorised into three teams: small, center, and enormous.

Our discovering has an vital implication for the literature on the micro-origins of combination fluctuations. The research talked about above emphasise the significance of the community construction within the context of the combination fluctuation pushed by microeconomic shocks. Nonetheless, it’s implicitly assumed that the propagation of the shocks is homogeneous throughout companies. Due to this assumption, the influence of microeconomic shocks is proportional to the variety of hyperlinks (i.e. transaction relationships) that the agency has. Since giant companies have transactions with many small suppliers and prospects, or a unfavorable diploma of assortativity (e.g. Bernard and Moxnes 2018, Bernard et al. 2014, Lim 2018, Bernard et al. 2019), the mannequin predicts that shocks to those giant companies propagate throughout an economic system. In distinction, our discovering means that the position of huge companies in demand-shock propagation is proscribed as a result of demand-shock propagation doesn’t happen by these hyperlinks between giant prospects and small suppliers. Demand shocks to giant companies are transmitted solely to their giant suppliers and don’t unfold additional throughout an economic system.

An extra vital message from our evaluation is that hyperlinks by which demand shocks are inclined to propagate and hyperlinks by which demand shocks stop to propagate coexist. In different phrases, connecting the previous hyperlinks in an input-output community permits us to determine the route of the demand-shock propagation. Figuring out the propagation route can also be related to policymakers as a result of we are able to assess the effectiveness of coverage measures comparable to subsidies to focused companies extra exactly. Our discovering is step one for this objective.

Editor’s observe: The primary analysis on which this column is predicated (Arata and Miyakawa 2022) first appeared as a Dialogue Paper of the Analysis Institute of Financial system, Commerce and Trade (RIETI) of Japan.

References

Acemoglu, D, U Akcigit and W Kerr (2016), “Networks and the macroeconomy: An empirical exploration”, NBER Macroeconomics Annual 30(1): 273–335.

Acemoglu, D, V M Carvalho, A E Ozdaglar and A Tahbaz-Salehi (2012), “The Community Origins of Mixture Fluctuations”, Econometrica 80(5): 1977–2016.

Arata, Y and D Miyakawa (2022), “Demand Shock Propagation by an Enter-Output Community in Japan,” RIETI Dialogue Paper Collection 22-E-027.

Athey, S, J Tibshirani and S Wager (2019), “Generalized random forests”, The Annals of Statistics 47(2): 1148–1178.

Barrot, J and J Sauvagnat (2016), “Enter Specificity and the Propagation of Idiosyncratic Shocks in Manufacturing Networks”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(3): 1543–1592.

Bernard, A B, E Dhyne, G Magerman, Okay Manova and A Moxnes (2019), “The origins of agency heterogeneity: A manufacturing community method”, Technical report, Nationwide Bureau of Financial Analysis.

Bernard, A B and A Moxnes (2018), “Networks and commerce”, Annual Evaluate of Economics 10: 65–85.

Bernard, A B, A Moxnes and Y U Saito (2014), “Geography and agency efficiency within the Japanese manufacturing community”, Technical report, RIETI.

Boehm, C E, A Flaaen and N Pandalai-Nayar (2019), “Enter Linkages and the Transmission of Shocks: Agency-Degree Proof from the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake”, Evaluate of Economics and Statistics 101(1): 60–75.

Carvalho, V M, M Nirei, Y U Saito and A Tahbaz-Salehi (2021), “Provide chain disruptions: Proof from the Nice East Japan Earthquake”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 136(2): 1255–1321.

Kisat, F and M Phan (2020), “Shopper demand shocks & agency linkages: Proof from demonetization in India”, obtainable at SSRN 3698258.

Lim, Okay (2018), “Endogenous manufacturing networks and the enterprise cycle”, Working Paper.

Wager, S and S Athey (2018), “Estimation and inference of heterogeneous remedy results utilizing random forests”, Journal of the American Statistical Affiliation 113(523): 1228–1242.