When the first trailers for Mani Ratnam’s Ponniyin Selvan were released, I was more than a little concerned. The roars of trumpets and the beating of drums, the screaming armies and overly muscular actors, and the marketing claim that this was a “Golden Age for Tamils” all seemed to point to one thing. I wrote: “…the film is part of a decades-long attempt to reclaim the medieval Chola dynasty as icons of muscular nationalism.” I was wrong. The nationalism of Ponniyin Selvan is not muscular, but something more interesting.

What I will try to do here is contrast the historical Cholas with Mani Ratnam’s depiction. Through most of the 20th century, academics, literati, cultural connoisseurs, museums, and media magnates have added layer upon layer of mystique and reverence to the Cholas, to the point where they are better known than any medieval Indian dynasty. They are seen as the originators of almost everything held to be “classical” in Tamil culture, from architecture to dance. And their conquests are spoken of with reverence and admiration, a sign of national virility and civilisational power.

This is not who the Cholas were, but it is who they have become. Understanding both reveals how, in South India, myths can in a very real sense become history. (Spoilers for Ponniyin Selvan ahead.)

Violence and the Ideal King

Ponniyin Selvan begins with a dramatic battle scene, where the army of the Chola crown prince Aditta Karikalan (Vikram) storms a city — probably meant to be Kanchi—and defeats the Rashtrakuta king Khottiga. While Aditta is a dashing cavalryman supported by a corps of (anachronistic) catapults, Khottiga merely stands by looking bewildered until the city is lost. This is an elegant visual metaphor for how the Cholas have come to be seen: other dynasties, it seems, could often do little more than stand by and be helplessly overpowered by Chola military might.

The military successes of the historical Cholas are certainly impressive, and require explanation. Media depicts wars and battles as glamourous, involving dashing heroes running full tilt at each other across battlefields, and then indulging in one-on-one duels. But battles are won not by individuals, but by formations. Gathering, training and feeding the men in those formations was a challenge for every premodern state.

This was a particular issue in the Tamil-speaking regions of medieval South India. While royals were important agents of historical change, they were not the only ones. For at least 500 years before the emergence of the imperial Cholas, the Kaveri river valley had been a heterarchical zone, with many competing and overlapping power centres: landlords, village assemblies, Brahmin settlements, temple trusts, merchant emporia. These groups were well-capable of organising themselves and undertaking large-scale projects. In Gifts of Power: Lordship in an Early Indian State, historian James Heitzman argues that even before the consolidation of the Chola state in the late 10th century, local groups had successfully harnessed most of the irrigation potential of the Kaveri River Valley, collaboratively constructing canals, tanks and dams.

With such self-sufficiency, one might wonder why these groups were willing to send their men to kill and be killed on distant battlefields. Royals used a variety of methods to mobilise manpower from them. The Cholas, for example, developed a model based on the portrayal of the king as a successful (and generous) military leader.

Part of this was the name “Chola” itself. It had been the name of an ancient Tamil dynasty that patronised (and was immortalised by) the wandering bards of the Sangam period (c 300 BCE–300 CE). The dynasty of Vijayalaya Chola — the ancestor of Rajaraja I — rose to power in the 9th century CE, and it is very doubtful that they were indeed their descendants. Nevertheless the name brought with it prestige, and allowed the medieval Cholas to portray themselves as warrior-heroes in the same way as those ancient kings had been. They were able to create a system of honours wherein working for the Chola king became a marker of status. In many inscriptions we see local notables using court-granted titles — such as “Rajaraja’s Noble”—rather than their own names.

The medieval Cholas also took care to intermarry with powerful local dynasties wherever they could. One particularly successful alliance was with the Irrukkuvels of Kodumbalur, who served as the generals of the early Chola kings. The Irrukkuvels were also closely tied to the powerful merchant corporation known as the Ainnuruvar or Five Hundred, who appear to have had a de facto alliance with the Chola state. Neither these merchants nor the dozens of queens that Chola kings had appeared in Ponniyin Selvan. Its depiction of statecraft is based on the morality of the 20th century, which sought heroic figures in the past and to fit them to modern-day notions of “good” and “bad”.

It is sometimes striking (and disturbing) how far the Cholas were from our own morality. Acts of extreme violence against enemy cities, and the capture of their rivals’ women are frequently described in their inscriptions — usually portrayed as being done with little to no effort. For example, in the Karandai Tamil Sangam Plates of Rajendra I, verses 54–55:

“While that great city was burning amidst thousands of series of flames of the fire thrown by his army, the women, moving in the open spaces of high palatial residences inlaid with varied jewels, appeared on account of the nets of smoke rising from the fire like the lightning moving frequently in the midst of groups of clouds… This sportive warrior king captured, even remaining in his own capital, all their wealth and vehicles along with their spotless fame, after having burnt Manyakheta by his army which was the residence of the Chalukyas…”

This brings with it the implication that such military successes were a sign of the ruler’s virility and power, and by extension, their right to rule. If dozens upon dozens of surviving Chola inscriptions are any indication, this is how they wished to be seen. And yet, in Ponniyin Selvan, Aditta Karikalan and his violent conquests are portrayed as morally in the wrong. Such destruction and thirst for expansion, Aditta explains, are a result of heartbreak, and he does all this in order to forget a lost love. So the film has brought up — and rejected — one model to explain Chola expansion. And yet it has the task of setting the stage for the future expansion and conquests of another Chola king, the Ponniyin Selvan or “Kaveri’s Beloved” of the title: Rajaraja I. After telling us that Aditta is somehow in the wrong, it must now establish that Rajaraja will somehow be in the right. It does so in a most interesting way.

The Real Rajaraja Chola

After the film’s intermission, we are introduced at last to Aditta Karikalan’s younger brother: Arulmozhi Varman (Jayam Ravi), the future Rajaraja Chola. When we first see him, he is, once again, depicted as a dashing cavalryman like his brother, fighting on the Lankan shore (historically, nothing of the sort happened during this time; Rajaraja’s Lankan adventures were at least 20 years away). As the camera zooms out from the battlefield, we see a beach littered with corpses. It is natural to ask: if he is just as violent and militarily successful as his brother, what makes Arulmozhi better than him? Why should we root for him and look forward to his eventually taking the Chola throne?

The question is immediately answered in the next scene, where Arulmozhi is invited by a major Lankan Buddhist Sangha to take the Lankan crown and rule them. The monks have, apparently, seen a sign that Arulmozhi will be a great king just like the ancient emperor Ashoka. Arulmozhi, after reverentially dropping jasmine flowers on an idol of the Buddha, humbly refuses. What the movie is trying to say is that Arulmozhi is battling the Lankan royalty but not the people; he fights only for his king and country, not for personal gain. The Lankan “people”, as represented by the Sangha, actually want him to rule them, not their current king. And so his violence is justified. The soldiers he has just slaughtered are, after all, faceless, and there should be no moral qualms about killing them. This is the most surprising of Ponniyin Selvan’s ideas: that medieval kings ruled, killed and conquered by the mandate of the people.

The film is very clear about why we should root for the Cholas (or, at least, for Arulmozhi’s branch of the family). These Cholas are the beloved of their people, and they in turn love their subjects. The troops of a rival faction refuse to carry out their mission when they learn that they are there to arrest the beloved Arulmozhi. Arulmozhi’s elder sister Kundavai (Trisha) declares to Aditta that she will do anything for “the Chola people”. In the beginning of the film, Aditta’s companion-in-arms Vallavaraiyan Vandiyadevan (Karthi) gallops through Chola territory, regaled by commoners singing about how much they love “the Chola country”. Of course, such concepts are completely out of place in the 10th century.

Through most of history, people identified not with kingdoms and rulers but with their villages, communities, and local magnates. This was doubly so in the already-heterarchical Kaveri River Valley, where the Cholas often had minimal authority at the local level — in comparison to the landlords and assemblies that decided matters of revenue, taxation, and the distribution of labour. From a historical perspective, one might say that the successes of Rajaraja I were remarkable not because of “the people” but, in a sense, despite them. People do not gather themselves into enormous armies and build monumental temples out of adoration for a distant king, but because the king is able to successfully coerce them into doing so. For the historical Rajaraja I to have achieved what he did is a sign of a political and military mind of almost unbelievable capabilities, and it is no wonder that his career permanently transformed the shape of Southern India.

Women and the Cholas

Early in the film, as Vandiyadevan listens in on a conspiracy, various vassal chiefs mock the Chola king (Prakash Raj) for seeking advice from his daughter Kundavai. When Kundavai appears later, she is introduced against a backdrop of smiling, darker-skinned young girls and accompanied by other princesses such as Vanathi (Shobhita Dhullipala), the future wife of Arulmozhi. (All of these princesses appear very happy with their subordinate position at the Chola court; the only people unhappy with Chola rule are, according to the film, morally inferior or villainous).

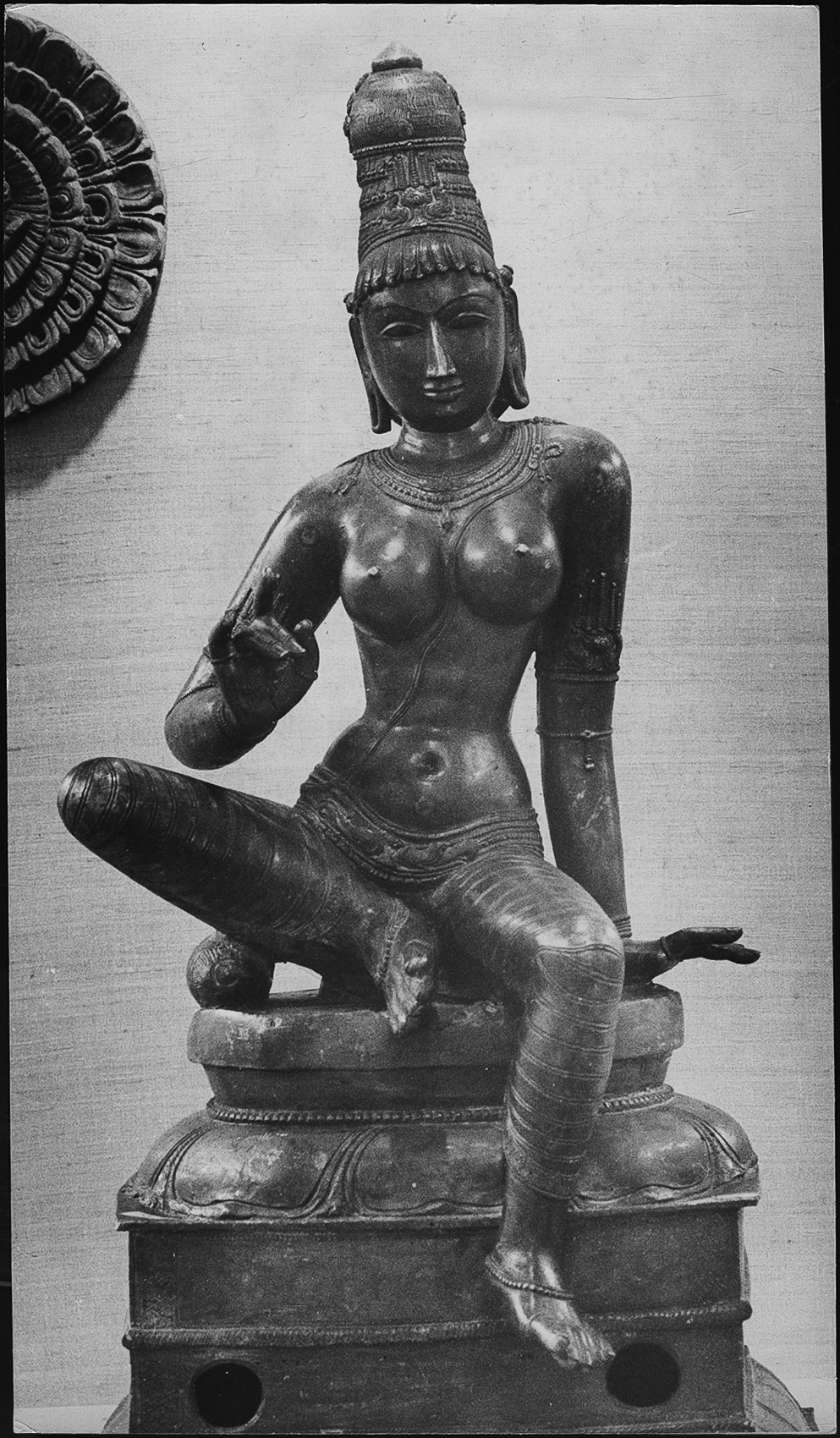

These portrayals are inaccurate for multiple reasons. In the last edition of History, Southside we saw how medieval Indian royal women were often highly-qualified, ambitious, and trained to lobby for their families at court. It was by no means remarkable (especially in South India) for women to occupy public roles. In fact, the Chola queen Sembiyan Mahadevi, Kundavai’s great-aunt, had already spent much of her career making public endowments to temples, an activity usually associated with male rulers. The film hand-waves this away as being simply out of piety rather than politics.

But perhaps the biggest inaccuracy is the idea that most women were happy at the Chola court. In The Service Retinues of the Chola Court, historian Daud Ali examines an institution called the velam, which appears in Chola inscriptions from the 10th through the 13th century. The velam, usually led by a Chola queen, consisted of the female retinues that served royalty, and consisted of women either purchased, received as tribute from defeated kings or kidnapped from sieges and battles. A plethora of historical sources support his, including the Pali Culavamsa, which describes how the armies of Rajaraja Chola seized the Lankan queen and carried her back to the mainland. Just like today, it was possible for some women to be powerful while also participating in the oppression of other women—a fact which the film conveniently ignores.

A truly accurate film about the Cholas might be rather darker and more morally complex than Ponniyin Selvan — and perhaps also much less amenable to contemporary sensibilities. While much of the world turns to grittier depictions of royalty, it’s worth asking why we in India still require royals to be “good” and glamourous to be worth watching. The story of the brilliant, brutal Chola kings who took their kingdom from obscurity to near-complete dominance in South India, and the equally brilliant people they competed with and subjugated, the unjust but vibrant world they shaped together—that story is yet to be told, but I will wait for it with patience. Until then, Ponniyin Selvan 2 is coming out next year.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian and author of Lords of the Deccan

The views expressed are personal

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading