This article is an onsite version of our Europe Express newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday and Saturday morning

Welcome back. Last July, Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s government published Germany’s first comprehensive China strategy. “China has changed. As a result of this and China’s political decisions, we need to change our approach to China,” the 64-page document stated.

Are Germany’s China policies changing a great deal or not much? I’m at [email protected].

It hasn’t been a smooth start to the year for Scholz’s three-party coalition. This week, the national statistics office reported that Germany’s gross domestic product contracted by 0.3 per cent in 2023, the worst performance among the world’s major economies.

Besides that, strikes and protests have broken out across the country, and the popularity of the government’s three parties — Scholz’s Social Democrats, the Greens and the liberal Free Democrats — is plunging.

Germany, like its European allies, is striving to maintain financial and military support for Ukraine in its war of self-defence against Russia. Finally, Germany worries about the consequences of a possible victory for Donald Trump in November’s US presidential election.

China: competitor, threat, partner — or all three?

These circumstances make it a challenging moment to recalibrate Germany’s China policies — all the more so, because of the two countries’ exceptionally close economic relationship. China was Germany’s main commercial partner in 2022 for the seventh consecutive year, with goods worth almost €300bn traded between them.

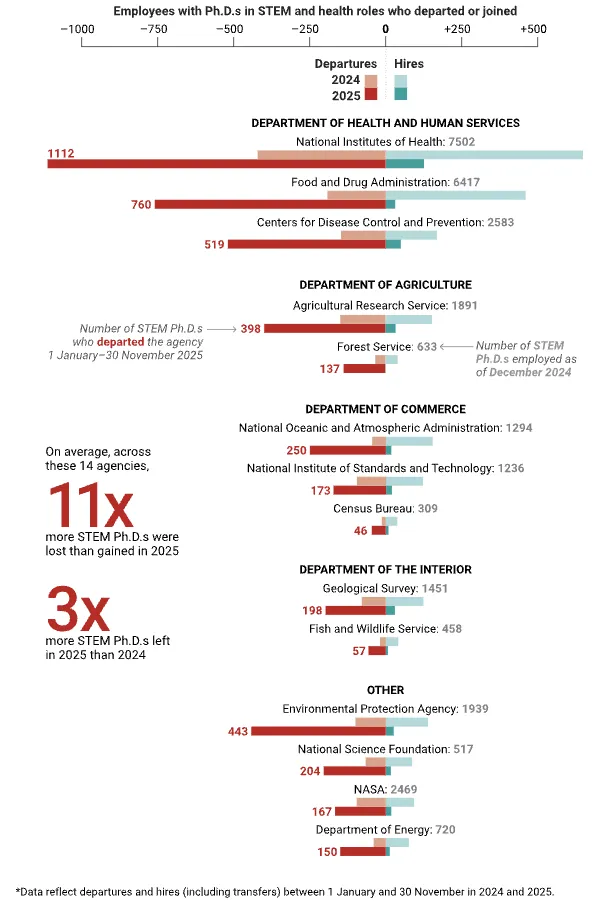

True, Germany’s bilateral trade balance with China has turned into a sharp deficit (Chinese exports to Germany were worth €192bn in 2022, against German exports worth €107bn to China), as this chart by BNP Paribas shows.

But German business is deeply committed to the Chinese market in terms of investment, manufacturing and sales as well as imports of essential products and materials. German direct investment in China stood at €102.7bn in 2021, against a mere €4.6bn worth of Chinese direct investment in Germany.

China’s far-right friends in Germany

Increasingly, the German political establishment regards China in certain respects as an economic rival and a security threat, as well as a partner with which it is desirable and even necessary to continue co-operation.

However, one party — the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), which has risen to second place in opinion polls — sees matters differently. Petr Bystron, its foreign policy spokesman, last year denounced Germany’s China strategy as an “attempt to implement green-woke ideology and US geopolitical interests under the guise of a strategy for German foreign policy”.

We should keep in mind that Alice Weidel, the AfD’s co-leader, knows China well. A former employee at investment bank Goldman Sachs, she lived there for six years on an academic scholarship and speaks Mandarin.

It’s therefore not entirely accurate to say there is a solid German consensus behind the new China strategy, either in the political world or in business.

However, German public opinion has come to see China in a sceptical light. In this ARD DeutschlandTrend poll, published in March 2023, some 83 per cent of respondents said China wasn’t a trustworthy partner, against 8 per cent who said it was.

This makes China roughly as unpopular as Russia in the eyes of the German public.

Business wings make the German eagle fly

Resetting German policy on China is no simple task, as became clear at a conference this month held by the Hanns Seidel Stiftung, a German public policy foundation, and the University of Cambridge’s Centre for Geopolitics.

On one hand, there’s the classic view of German big business, summed up by one conference participant in these words: “The German eagle flies because German industry gives it wings.”

This is a way of saying that, after the second world war, West Germany and then (from 1990) the reunited Germany entrusted its security to the US and Nato. It didn’t develop a strategic culture of its own. Instead, it relied largely on its industrial and commercial prowess, channelled partly through the EU, to acquire international influence and prestige.

On the other hand, some of this has changed since Scholz’s landmark Zeitenwende speech of February 2022, just after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — a speech that promised Germany would step up its game in defence and security.

Then, last June, before the release of its China document, the government published Germany’s first national security strategy. It, too, spoke of the need for Berlin to take on an enhanced international role beyond the economic sphere it knew so well.

Clinging to the status quo

But this document attracted criticism for being a political compromise among Germany’s three ruling parties that, in the words of Ben Schreer, writing for the International Institute of Strategic Studies, was stuffed with “vague and intentionally imprecise language”.

Germans who specialise in security and defence, rather than business, question whether the Zeitenwende speech, the national security strategy and the China strategy add up to substantive changes in the nation’s policies, especially towards Russia and China.

As another conference participant put it: “Germany clings to a status quo that doesn’t exist any more in a way that’s almost delusional.”

In this view, Germany’s traditional impulse to rely on Wandel durch Handel — the idea that benign change in authoritarian systems like China’s will come about through expanded trade — is still active.

Is that too harsh? The language of Germany’s China strategy document is balanced but, in places, tougher than past government pronouncements.

For example, it says Germany is concerned that

China is endeavouring to influence the international order in line with the interests of its single-party system . . . China’s conduct and decisions have caused the elements of rivalry and competition in our relations to increase in recent years.

On economic ties, it says:

Whereas China’s dependencies on Europe are constantly declining, Germany’s dependencies on China have taken on greater significance . . . It is not our intention to impede China’s economic progress and development. At the same time, de-risking is urgently needed.

German business and ‘de-risking’

It’s an ugly word, but what does “de-risking” mean in practice for German business? It boils down to a diversification of supply chains and export markets — in this case, from China — in order to reduce Germany’s vulnerability to external shocks and pressures.

In this important piece for the Cologne-based Institut der Deutschen Wirtschaft, Jürgen Matthes and Thomas Puls say “the first signs of import-side de-risking are emerging”, but German industry’s dependencies on Chinese inputs are still high.

This is hardly surprising. Large companies in sectors such as cars, chemicals, mechanical engineering and electrical devices cannot abruptly switch from China to other countries as suppliers of essential items.

Indeed, as the BDI, Germany’s industrialists’ federation, puts it, the nation’s reliance on China for rare earths and other raw materials is now higher than its reliance on Russia for oil and gas.

One person at the London conference commented: “In terms of procurement of materials, semiconductors and batteries, you will find Chinese inputs across the whole value chain and it would take years to find substitute suppliers.”

India and south-east Asian countries are sometimes mentioned as potential substitutes, both as markets and as suppliers, but they lack China’s market size and its mature infrastructure.

China: good for German innovation and jobs?

The example of Germany’s car industry is illuminating. China is not only the world’s largest car market, reaping large profits for German manufacturers, but a fiercely competitive one.

In what is known as the “fitness centre argument”, supporters of maintaining or even extending operations in China say that companies like Volkswagen and BMW make better cars because Chinese conditions stimulate them to be as innovative as possible.

Another defence of investing and producing in China is that the revenues and profits of some German companies there are so high that they make it affordable to keep well-paid jobs in Germany.

Defending national security

All that said, German policymakers correctly make the point that business or academic ties with China shouldn’t be treated separately from national security considerations.

That is why the government has begun more rigorous screening of visa applications from Chinese researchers who want to study or work in Germany.

It’s also why Germany’s interior ministry proposed in September to make telecoms operators curb their use of equipment made by China’s Huawei and ZTE companies.

As German foreign minister Annalena Baerbock said in July, China’s role as a “systemic rival” is starting to overshadow its role as a partner because it is turning “more repressive internally and more aggressive externally”.

Germany’s China strategy marks a new approach in EU-China relations — a commentary by Lily McElwee and Ilaria Mazzocco for the Center for Strategic and International Studies

Tony’s picks of the week

Donald Trump’s resounding victory in Iowa’s Republican caucuses showed that the former president was able to expand his voter base to include counties with a younger, more affluent electorate, the FT’s Eva Xiao and Oliver Roeder report from New York

Russia’s courting of five large African states — Algeria, Egypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria and South Africa — is part of a diplomatic and trade strategy aimed at building an anti-western global order, Ivan Kłyszcz writes for the Stockholm Centre for Eastern European Studies

Recommended newsletters for you

Britain after Brexit — Keep up to date with the latest developments as the UK economy adjusts to life outside the EU. Sign up here

Working it — Discover the big ideas shaping today’s workplaces with a weekly newsletter from work & careers editor Isabel Berwick. Sign up here

Are you enjoying Europe Express? Sign up here to have it delivered straight to your inbox every workday at 7am CET and on Saturdays at noon CET. Do tell us what you think, we love to hear from you: [email protected]. Keep up with the latest European stories @FT Europe