A litre of beer has never cost so much at Munich’s Oktoberfest. But that is not deterring the crowds, whose willingness to shell out €14.40 on a Maß of pilsener offers vital clues about consumer confidence in Europe’s largest economy.

Jörg Biebernick, chief executive of Paulaner, one of Germany’s largest breweries, learnt the hard way how big the Oktoberfest is this year. He tried to get a table for a group of friends on a recent evening and was told he had no chance. “The tents are all fully booked,” he said. “And this despite inflation.”

Biebernick was speaking in the Paulaner tent, a vast hall in Munich’s Theresienwiese fairground that daily dispenses thousands of litres of beer to revellers, many of them clad in lederhosen and dirndls. By midday tables were already filling up and the oompah bands were in full throttle.

But “by 8.30pm things really blast off”, said Biebernick. “It’s bombastic.”

For more than a year, Germany has been stuck in an economic downturn, precipitated by a brutal surge in energy costs that snuffed out the country’s tentative post-pandemic recovery.

And the outlook remains gloomy. A joint forecast by the country’s leading economic think-tanks on Thursday predicted gross domestic product would shrink by 0.6 per cent this year. In the spring, they said it would actually grow by 0.3 per cent.

Oliver Holtemöller, of the Halle Institute for Economic Research, said German industry and private consumption were recovering “more slowly than we expected in the spring”.

Stubbornly high inflation, the researchers said, was hurting ordinary citizens, rising interest rates had crippled the construction industry and uncertainty caused by the government’s erratic energy policies was souring the mood in German boardrooms.

But there was one ray of light: German purchasing power, the think-tanks said, was growing. Energy prices had fallen from their 2022 highs and export prices had risen strongly, showing that companies were succeeding in passing on price increases to their international customers.

The most important factor, however, was rising wages. Incomes is general are set to increase, largely thanks to a basic allowance for jobseekers introduced by the government late last year and a boost to pensions scheduled for 2024.

“Wages and transfer income such as benefit payments are going to pick up significantly in the second half of 2023 and then even more strongly next year,” said Stefan Kooths, director at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy.

“That means more purchasing power will flow to private households and that will in turn boost consumption-related sectors of the economy.”

Numbers released in August showed German wages rose at a record annual pace of 6.6 per cent in the second quarter, the highest rate of increase since such records began in 2008.

That boosted German annual wage growth above the country’s consumer price inflation rate for the first time since 2021. Household incomes appeared to be finally catching up with the cost of living.

“Private consumption has been very weak and that has caused real problems in the past, especially around the turn of the year,” said Kooths. “But that’s changing now.”

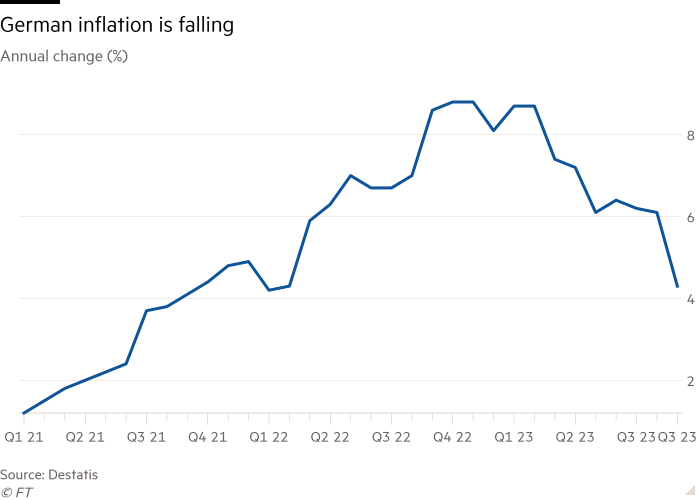

Inflationary pressures also appear to be easing, with the annual rate plunging to 4.3 per cent in September, its lowest level in two years. In August it was 6.4 per cent.

This year’s Oktoberfest offers evidence of the brightening mood. By its halfway point, some 3.4mn people had attended the Wiesn, as it is known locally, 100,000 more than in 2019, when guests spent an eye-watering €1.25bn on its drinks, food and fairground rides. The Wiesn attracted 1mn visitors on the first weekend, compared with just 700,000 last year.

The contrast to 2022 is stark. “Last year was the most terrible weather in my experience,” said Andreas Steinfatt, Paulaner’s head of trade, marketing and regional brands. “It rained on 14.5 of the 17 days, and the temperature never rose above 12 degrees. You needed to wear scarves.”

This year Munich is enjoying an Indian summer, with the sun shining nearly every day. Yet the outlook is not completely undimmed — prices are at historic highs.

“Everything’s going to be more expensive this year,” said Biebernick. A litre of beer costs between €12.60 and €14.90, 6.1 per cent more than last year. A plate of pork knuckle, the traditional Oktoberfest dish, costs €25, up from €20 in 2019.

Brewers said they had no choice but to pass on higher input costs. “Malt and hop prices have doubled in the last two years,” said Christian Dahnke, Paulaner’s master brewer. Sugar, too, is more expensive, as is the cost of aluminium for cans.

But no one seems bothered by the extra expense, said Biebernick, who expects 7mn litres of beer to be drunk in the course of the 18-day fest.

“I don’t think people are deterred by the high prices,” he said. “Purchasing power in Munich is in any case around the highest in Germany, if not in Europe.”