Frank Gilbert, a preservationist who helped save Grand Central Terminal from being ravaged by a 55-story skyscraper and within the mid-Nineteen Sixties incubated New York Metropolis’s pioneering landmarks regulation, which undergirded preservation actions throughout the nation, died on Could 14 in Chevy Chase, Md. He was 91.

The trigger was pneumonia and problems of Parkinson’s illness, his spouse, Ann Hersh Gilbert, mentioned.

Mr. Gilbert, a lawyer who had been New York Metropolis’s legislative lobbyist in Albany, had been instrumental in drafting town’s belated barn-door-closing statute following the demolition in 1963 of Pennsylvania Station, the Beaux-Arts railroad hub designed by McKim, Mead & White on Manhattan’s West Aspect.

The laws, handed by the Metropolis Council and signed by Mayor Robert F. Wagner in 1965, declared that town’s international standing “can’t be maintained or enhanced by disregarding the historic and architectural heritage of town and by countenancing the destruction of such cultural belongings.”

The regulation created the Landmarks Preservation Fee and empowered it to designate buildings that have been no less than 30 years outdated and had both historic or architectural advantage, and to spare them from improvement or demolition.

Mr. Gilbert served as the primary secretary of the newly minted fee from 1965 to 1972 after which as govt director by 1974. All through, the destiny of Grand Central loomed giant for him.

“I used to be involved as a result of the chairman of the landmarks fee had mentioned to me what occurred to Penn Station should not occur to Grand Central,” Mr. Gilbert recalled in an interview with the New York Preservation Archive Venture in 2011.

“I assume from the very starting, my job was actually to guarantee that we comply with due course of and didn’t slip on a banana peel,” he added. “I acknowledged how severe the scenario was. My main thought was actually to be very cautious, and be ready for a really difficult scenario.”

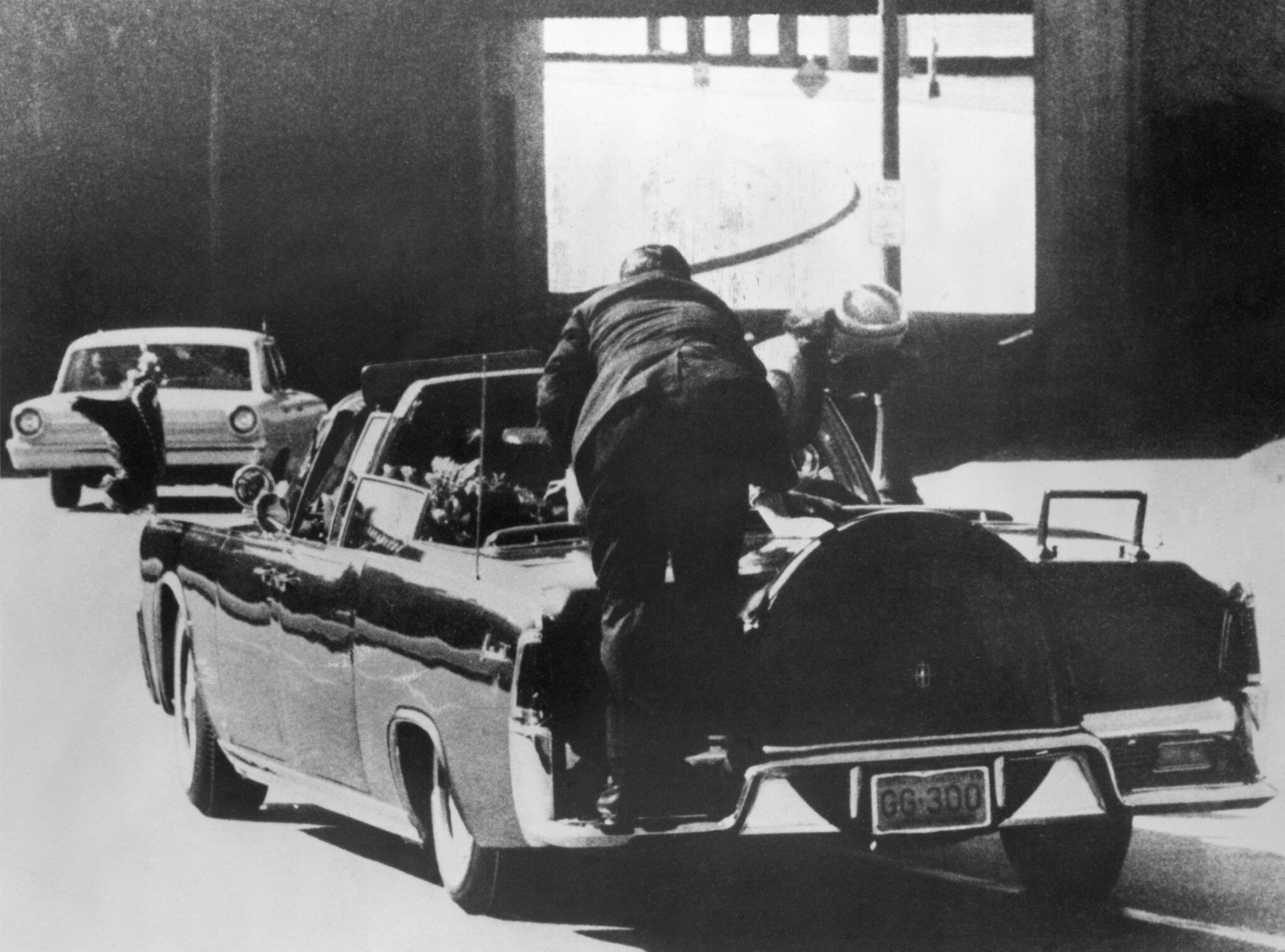

The failing Penn Central railroad firm hoped to construct a skyscraper above Grand Central Terminal, which it owned, and to make use of rents from the places of work to subsidize the corporate’s deficits from declining prepare journey.

However the fee declared the terminal a landmark in 1967 and determined that each one of Penn Central’s proposed designs for the skyscraper would eclipse the terminal’s architectural distinction.

Penn Central sued. Absolutely 9 years later, a State Supreme Courtroom justice voided the landmarks designation, ruling that stopping the bankrupt railroad from incomes the revenue it could obtain from the workplace tower would trigger “financial hardship” and due to this fact amounted to an unconstitutional taking of its property.

Mr. Gilbert and different defenders of Grand Central rallied assist from a large spectrum of preservationists, together with outstanding architects and boldface names like Jacqueline Onassis, to uphold the landmark designation as town pursued appeals in larger courts.

In 1978, the USA Supreme Courtroom affirmed town’s authority to protect a landmark. The court docket discovered that the landmark designation didn’t intervene with Grand Central’s use as a railroad terminal, and that the corporate couldn’t declare that development of the workplace constructing was vital to keep up the positioning’s profitability. The railroad had conceded that it might earn a revenue from the terminal “in its current state.”

The Supreme Courtroom’s 6-3 resolution cited an amicus transient drafted by Mr. Gilbert, who by then was assistant normal counsel of the Nationwide Belief for Historic Preservation in Washington. His transient identified that scores of cities throughout the nation, together with New Orleans, Boston and San Antonio, had already accredited landmark preservation legal guidelines modeled on the New York statute.

Paul Edmondson, the president and chief govt of the Nationwide Belief, characterised Mr. Gilbert as “an enormous within the area of preservation regulation.”

“Past his crucial function in growing and defending New York Metropolis’s landmarks preservation regulation,” Mr. Edmondson mentioned in an announcement, “he was accountable for the safety of hundreds of historic properties and neighborhoods throughout the nation by his work in serving to communities develop historic districts.”

Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel, an early appointee to New York’s landmarks fee and its longest-serving member, mentioned of Mr. Gilbert in an e-mail: “All the time desirous to do the precise factor, he labored to steadiness the complicated wants of all events — property homeowners, the general public, the press, builders and preservationists.”

Frank Brandeis Gilbert was born on Dec. 3, 1930, in Manhattan to Jacob Gilbert and Susan Brandeis Gilbert, each attorneys. His mom was the daughter of Louis D. Brandeis, the USA Supreme Courtroom justice.

After graduating from the Horace Mann College within the Bronx, Mr. Gilbert earned a bachelor’s diploma in authorities from Harvard School in 1952, served within the Military from 1953 to 1955, and graduated from Harvard Regulation College in 1957.

From 1973 to 1993 he was chairman of the graduate board of The Harvard Crimson, the scholar newspaper. Earlier this month, he was among the many Crimson alumni who signed a letter supporting Harvard’s Jewish neighborhood and condemning the paper’s editorial endorsement of the so-called Boycott, Divest, Sanctions motion towards Israel on behalf of what it referred to as a free Palestine.

“The BDS motion claims to hunt ‘justice for the Palestinians’ — a objective we share — however, really, it seeks the elimination of Israel,” the letter mentioned.

Mr. Gilbert joined the authorized division of the Public Housing Administration in Washington in 1957 and went to work for New York’s metropolis planning division two years later. He married Ann Hersh in 1973. She is his solely speedy survivor.

From 1975 to 1984, Mr. Gilbert was the landmarks and preservation regulation chief counsel for the Nationwide Belief for Historic Preservation. He served because the belief’s senior area consultant till 2010.

He suggested state and native governments on preservation laws and on points relating to the designation of particular landmarks and the institution of historic districts, like these New York Metropolis had created in SoHo, Brooklyn Heights, Greenwich Village and Chelsea.

Mr. Gilbert recalled within the Archive Venture interview that when the fledgling fee formally chosen its first batch of landmarks, The New York Herald Tribune’s headline declared, “Twenty Buildings Saved!”

“My response at that time,” he mentioned, “was, ‘20 buildings designated,’ and we had numerous work to do on these 20 buildings earlier than they have been saved.”

He was proved prescient by the decade-long authorized battle then approaching over Grand Central and the disputes with the actual property trade and with particular person builders over extending the fee’s powers to designate as landmarks the interiors of buildings in addition to whole neighborhoods.

By the fee’s fiftieth anniversary in 2015, it had designated 1,348 particular person landmarks, 117 interiors and 33,411 properties inside 21 historic districts.