Edward Price is principal at Ergo Consulting. A former British trade official, he also teaches at New York University’s Center for Global Affairs.

As the Great Accommodation gives way to the Great Uh-Oh, here’s the problem central bankers face: whither the policy rate?

Right now, the answer is easy. Up. Jay Powell is warning of “pain” and “unfortunate costs” for households and companies. Andrew Bailey says the Bank of England “will not hesitate to raise interest rates”. Christine Lagarde said the ECB “will do what we have to do, which is to continue hiking interest rates”.

Higher rates, however, will eventually spell recession, illiquidity and insolvency. That may challenge financial stability. If so — if crisis ensues — only a lower policy rate will do. Alas, lower rates exacerbate upward price pressures. After the “transitory inflation” snafu, swinging back to accommodation would cost central banks their remaining street cred. Under these circumstances their only option would be . . . a higher policy rate.

Whatever central banks do, is financial instability the ultimate threat?

Well yes, but don’t ask me. Ask the people in charge. Four economists from the New York Fed have recently released a revised version of a 2020 paper entitled The Financial (In)Stability Real Interest Rate, R**.

And what, pray tell, is r-star–star? Again, easy. If r-star is the natural real rate of interest associated with macroeconomic stability (caveat emptor), then r-star-star is the rate associated with financial stability. Cool. You can watch the paper being presented at a recent Fed event here. It’s engrossing.

Spoiler alert though. There’s a major catch.

Both conceptually and observationally r** differs from the “natural real interest rate” and from the observed real interest rate reflecting a tension in terms of macroeconomic stabilization versus financial stability objectives.

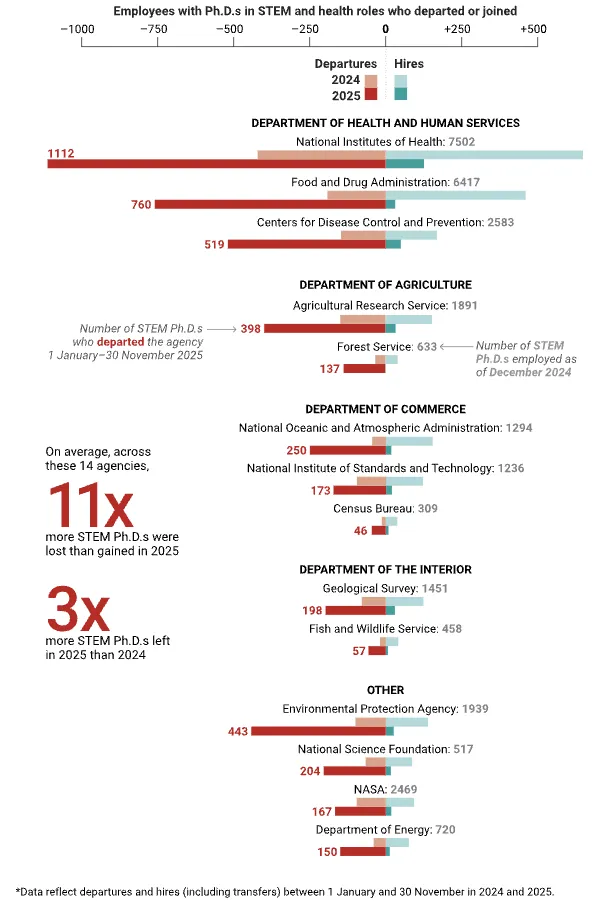

Great. Financial stability ≠ macroeconomic stability. R-star ≠ r-star-star. Moreover, the two part ways just when it matters most — a financial crisis (basically, whenever banking hits the wall). Behold these graphs:

This is a crisis model we’re talking about, so meanwhile GDP and investment fall while credit spreads rise. That’s any crunch.

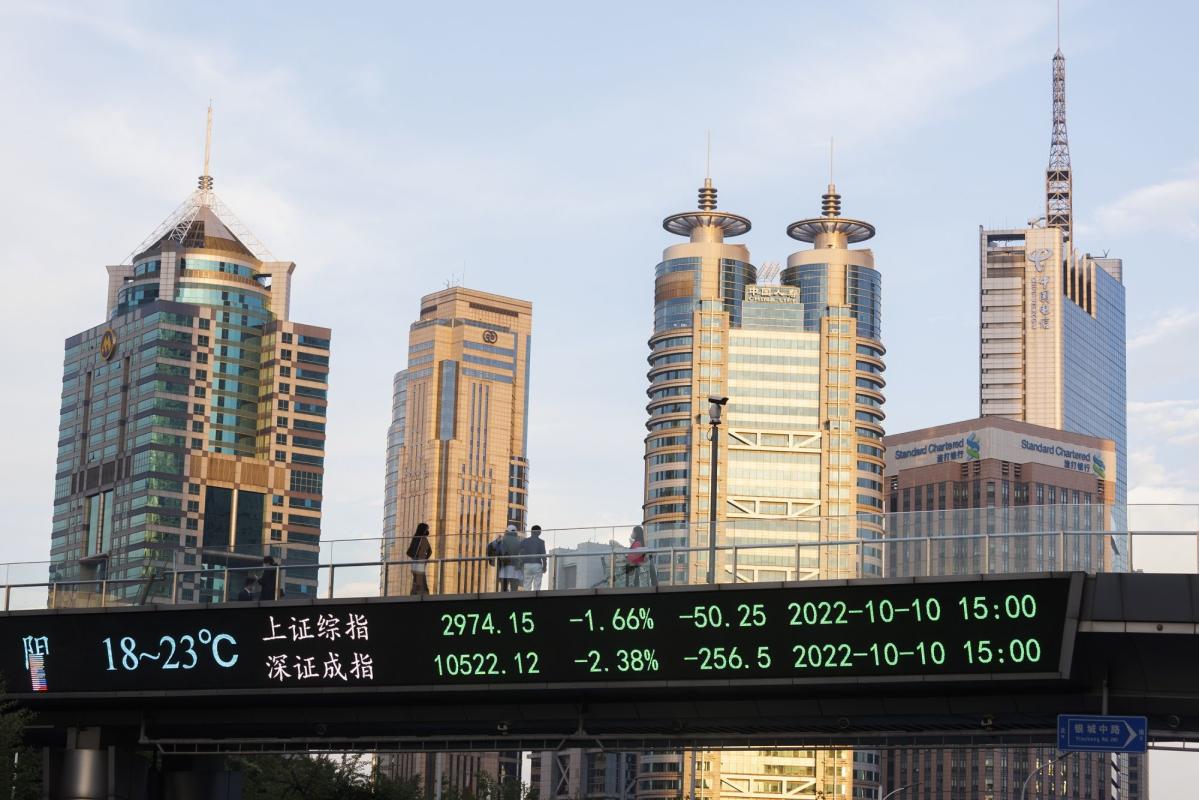

But here’s the thing: prices. You can’t reconcile these graphs with a lower policy rate. US inflation came in at 8.2 per cent in September. Oof.

We’re already seeing this tension play out. To choke inflation, American business leaders expect the Fed to spank labour. Bank of America expects a 5.5 per cent unemployment rate. Frankly, as Larry Summers has suggested, over 6 per cent wouldn’t be weird.

Consensus has now moved to the view a recession is likely next yr. The avg recession involves a 3% point increase in unemployment. The most benign involved an extra 1.5 % unemployment. Fed forecast of 4.5 peak is looking implausible. 6 seems a better guess https://t.co/mt5rOQfjn7

— Lawrence H. Summers (@LHSummers) October 17, 2022

So, the price mechanism and households (occasionally) need different interest rates. Full employment and price stability are (occasionally) at odds. Financial instability, meanwhile, will happily challenge both.

Basically, there are conditions under which the dual mandate (alias: internal equilibrium) must take a back seat to capital markets (alias: global equilibrium). As per the paper:

. . . “Greenspan’s put” . . . has been a feature of all financial stress episodes in the US [since the 1970s], with the only exception being the later part of the Great Financial Crisis . . . [in] general we note that financial stress episodes are associated with periods in which the real interest rate is above our measure of r**.

Translation: financial markets want their policy cut. Otherwise, they’re gonna pay you a little visit.

And when they do, you can forget whatever fed funds rate you think is appropriate for full employment and/or price stability.

Bravo to the NY Fed. This paper has, in all fairness, explained exactly what it is that financial instability does.