The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced renewed curiosity to understanding how family spending responds to revenue adjustments. The disaster hit incomes for a big share of households and lockdown restrictions meant that the autumn in combination spending was vital, with massive variations throughout households. Utilizing a big consultant survey of UK households, we research in a brand new paper how family expectations about their future monetary state of affairs might have an effect on their short-term marginal propensity to eat (MPC) out of optimistic revenue shocks (Albuquerque and Inexperienced 2022). Our essential findings level to an necessary function performed by family expectations in figuring out how consumption reacts to shocks.

Family spending out of revenue transfers has been low in the course of the pandemic

New datasets have allowed economists to estimate households’ MPC – the share of an increase in revenue {that a} shopper spends slightly than saves – fairly swiftly in the course of the pandemic (Baker and Kueng 2021, Vavra 2021). The obtainable proof factors to households largely saving or paying down debt when receiving a one-off fee (Armantier et al. 2020, 2021, Baker et al. 2020, Coibion et al. 2020, Crossley et al. 2020, Cox et al. 2020, Christelis et al. 2021). However there’s proof that the MPC out of optimistic revenue shocks is largest for low-income and liquidity-constrained households, and for households who suffered larger revenue falls relative to their pre-pandemic revenue.

There’s much less empirical proof and consensus concerning the hyperlink between family expectations and the MPC. In keeping with precautionary financial savings fashions, financially involved households are inclined to have decrease MPCs, in order to construct up financial savings to mitigate future detrimental revenue shocks (Aiyagari 1994, Jappelli and Pistaferri 2014). There’s some proof for the US (Baker et al. 2020) and EA (Christelis et al. 2021) in that path. However others discover little function for people’ macroeconomic expectations in explaining variations in MPCs (Coibion et al. 2020). And there’s proof for the UK that people who count on their monetary state of affairs to worsen or a job loss within the subsequent three months truly report a better MPC out of a hypothetical switch (Crossley et al. 2020). On this put up we due to this fact dig deeper into the hyperlink between monetary issues and family spending.

Spending out of a switch from family survey information

We use granular information protecting a balanced panel of seven,000 UK households collected within the Understanding Society Covid-19 Examine (Institute for Social and Financial Analysis 2020). Understanding Society is the UK’s essential longitudinal family survey. The Covid-19 Examine was launched to seize experiences of a subset of those households in the course of the pandemic. Our variable of curiosity, the MPC, is extracted from a number of questions in July 2020, November 2020, and March 2021 which ask households what they’d do over the following three months in the event that they have been to obtain a one-time hypothetical switch of £500.

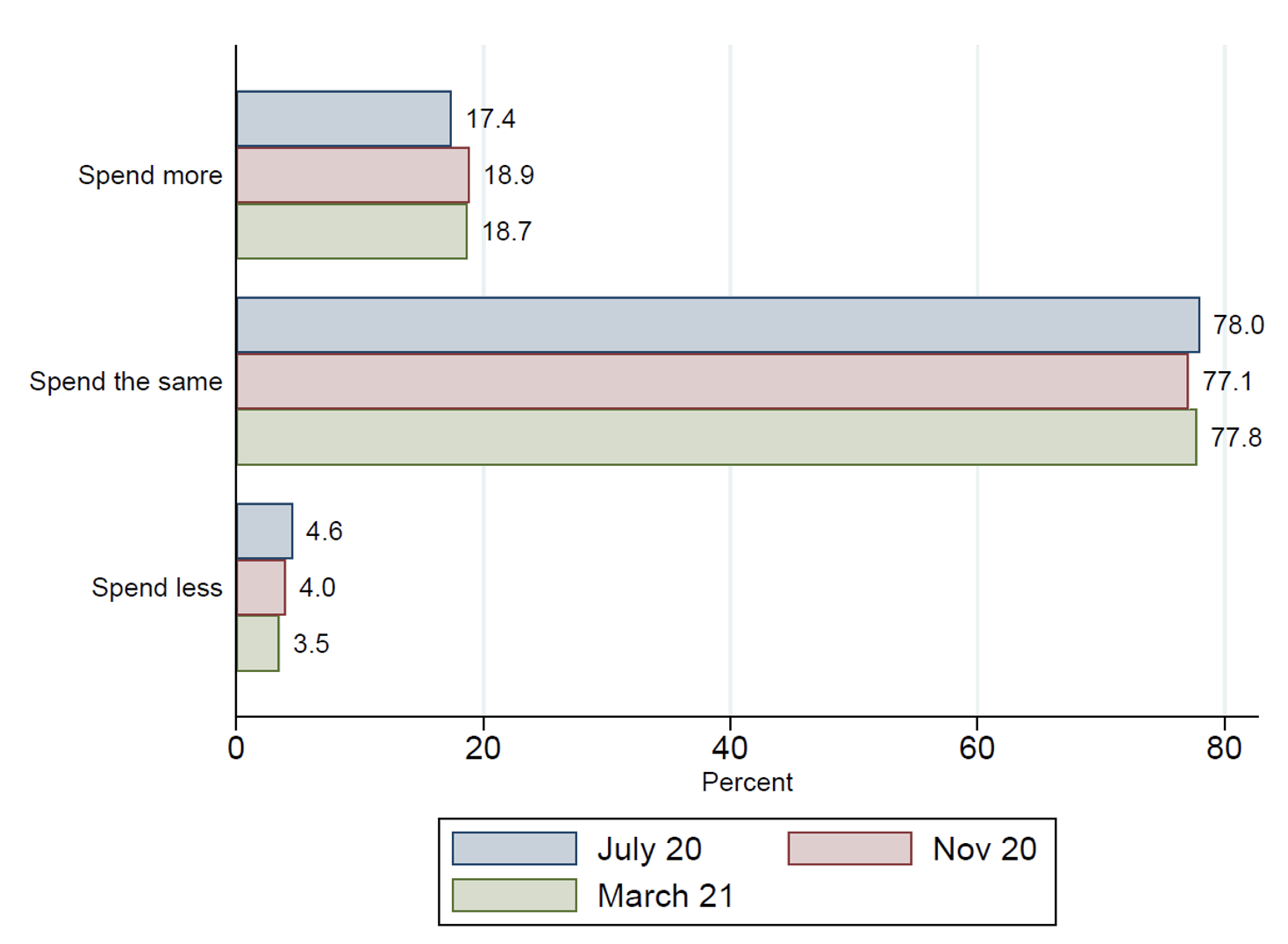

Determine 1 exhibits that round 78% of households wouldn’t change their spending in response to a one-time fee of £500. Round 18% would spend extra, whereas roughly 4% would spend much less. The responses are comparatively secure throughout the three survey waves. We then compute the family’s MPC because the reported pound consumption change divided by £500. We assume that MPCs differ between zero and one, in order that households who reported they’d spend much less or the identical are re-coded as having an MPC of zero. We discover that the typical elicited MPC throughout surveys stands at solely 11%.

Determine 1 Households’ response to a hypothetical fee of £500

Monetary issues in the course of the pandemic

The surveys additionally contained questions on family expectations, which permit us to discover the hyperlink between monetary issues and the MPC. These expectations relate to households’ monetary state of affairs within the subsequent three months, aligning with the time horizon of the MPC query. Our essential measure of economic issues focuses on households’ perceived probability of getting difficulties in paying payments and bills within the subsequent three months (starting from 0–100%).

In our baseline regressions we remodel the monetary issues variable right into a binary one, taking the worth of 1 if the family’s anticipated chance of economic misery is above the median within the pattern, and nil in any other case.

What determines monetary issues?

We hyperlink the Covid surveys to the Major survey to extract necessary pre-crisis family traits, corresponding to mortgage debt and financial savings. We then discover which traits correlate with monetary issues by working probit panel regressions throughout the three surveys. We embrace a big set of family traits: socio-demographic variables; monetary traits; subjective present monetary state of affairs; employment info; advantages; and well being issues.

We discover that households which can be involved about not having the ability to pay their payments within the quick time period are considerably extra more likely to fall into varied teams: already involved about their present monetary state of affairs; liquidity constrained; belong to low-income teams; renters or mortgagors; youthful, male, and ethnic minorities; furloughed; reliant on advantages; or employed in industries extra closely impacted by the pandemic.

The hyperlink between monetary issues and spending

We then run a number of panel regressions to uncover variations in MPCs throughout households in the course of the pandemic. Our dependent variable is the elicited MPC, ranging between 0 and 1 and our key explanatory variable is the binary monetary issues variable. We embrace a number of family controls, corresponding to financial savings, tenure, revenue and age, which is perhaps anticipated to correlate with a family’s spending selections. Along with our monetary issues variable, which signifies whether or not a family believes they are going to be worse off financially in three months’ time, we additionally embrace a variable indicating whether or not a family is discovering it tough to handle financially now. This enables us to tease out the function of short-term expectations about future monetary difficulties. If we didn’t management for a family’s present monetary state of affairs outcomes might simply mirror that some households are already struggling and so reply extra to an revenue shock.

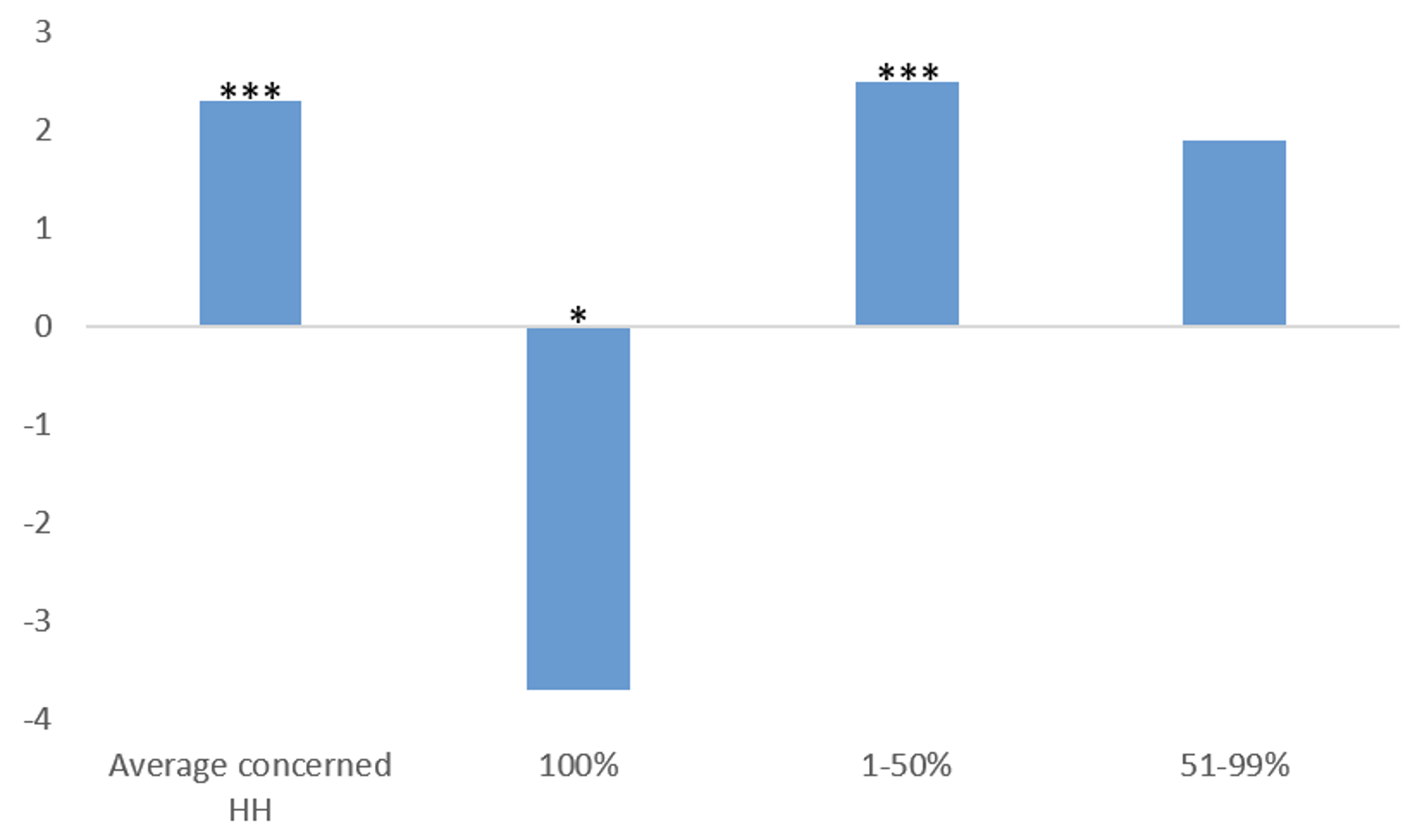

Monetary issues over the quick time period play a key function in explaining variations in MPCs throughout households in the course of the pandemic. We discover that financially involved households have an MPC that’s 2.3 pp bigger than households who usually are not involved (left bar in Determine 2). That’s 20% increased than the pattern common. This result’s strong to a number of checks, corresponding to different measures of economic issues, controlling for health-related issues, and to small adjustments to the design of the MPC query.

Determine 2 Marginal change in MPC relative to unconcerned households (share factors)

Notes: Estimates from a random results mannequin on the particular person stage, the place the dependent variable is the elicited MPC. Controls for full set of family traits. Commonplace errors in parentheses clustered on the particular person stage. Asterisks, *, **, and ***, denote statistical significance on the 10%, 5%, and 1% ranges.

We additionally test whether or not previous spending cuts, detrimental revenue shocks, mortgage debt, and the labour market state of affairs clarify why financially involved households have bigger MPCs. We might solely discover some tentative proof that a part of our end result could also be pushed by completely different shares of discretionary spending and reliance on advantages, however that is unlikely to play a big function.

We adapt our baseline specification to utilize the truth that our monetary issues variable ranges from 0% to 100%. We discover that households which can be reasonably involved, within the 1%-50% chance vary, are driving our essential outcomes (Determine 2). This implies that, so long as the subjective chance of being in monetary misery sooner or later is just not that giant, involved households will are inclined to spend a bigger fraction of the revenue windfall than different households. Against this, households which can be sure they won’t be able to pay their payments (100% chance) show the smallest MPC; these households save a bigger fraction of the switch to organize for tougher instances forward.

Whereas our outcomes could also be shocking from the attitude of a classical consumption mannequin, they’re much less shocking from a behavioural perspective. In behavioural fashions, households might compartmentalise revenue and spending into completely different ‘psychological accounts’ and funds inside these to assist make trade-offs and act as a self-control gadget (Duxbury et al. 2005, Milkman and Beshears 2009, Kahneman and Tversky 2013). Financially involved households is perhaps extra more likely to funds and deal with funds inside every tagged psychological account as distinct and imperfectly substitutable, making them extra more likely to spend out of a switch. There’s additionally proof that completely different preferences can drive variations in consumption behaviour (Laibson 1998, Aguiar et al. 2020, Vihriälä 2021). As an example, impatience might lead households to deliver consumption forwards, and might also correlate with a better chance of changing into financially distressed in future.

We have now proven that financially involved households are related to bigger MPCs out of optimistic revenue shocks. However what about detrimental revenue shocks? Sadly, the survey didn’t embrace questions on an revenue fall situation. We thus test whether or not financially involved households that confronted revenue decreases in the course of the pandemic have been extra more likely to lower their spending than unconcerned households that additionally skilled falls. Our outcomes counsel that financially involved households who had detrimental revenue shocks certainly lower consumption greater than unconcerned households, indicating that bigger consumption responses of the previous group is probably not unique to eventualities of optimistic revenue shocks.

Abstract

We used survey information in the course of the pandemic to discover how households who’re involved about their monetary future reply to a hypothetical optimistic revenue shock. We discover that, opposite to expectations, involved households intend to spend round 20% greater than others. Households which can be reasonably involved, slightly than those that are sure they won’t be able to pay their payments within the near-term, drive our essential outcomes.

Authors’ observe: The views expressed on this column signify solely our personal and will due to this fact not be reported as representing the views of the Financial institution of England, the Worldwide Financial Fund, its Government Board, or IMF administration.

References

Aguiar, M A, M Bils and C Boar (2020), “Who Are the Hand-to-Mouth?”, NBER Working Paper 26643.

Aiyagari, S R (1994), “Uninsured Idiosyncratic Danger and Mixture Saving”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 109(3): 659–684.

Albuquerque, B and G Inexperienced (2022), “Monetary Considerations and the Marginal Propensity to Devour in COVID Occasions: Proof from UK Survey Knowledge”, IMF Working Paper WP/22/47.

Armantier, O, L Goldman, G Kosar, J Lu, R Pomerantz and W Van der Klaauw (2020), “How Have Households Used Their Stimulus Funds and How Would They Spend the Subsequent?”, Liberty Avenue Economics, 13 October, Federal Reserve Financial institution of New York.

Armantier, O, L Goldman, G Kosar and W and Van der Klaauw (2021), “An Replace on How Households Are Utilizing Stimulus Checks”, Liberty Avenue Economics, 7 April, Federal Reserve Financial institution of New York.

Baker, S R, R A Farrokhnia, S Meyer, M Pagel and C Yannelis (2020), “Revenue, liquidity, and the consumption response to the COVID-19 pandemic and financial stimulus funds”, VoxEU.org, 16 June.

Baker, S R and L Kueng (2021), “Family monetary transaction information”, NBER Working Paper 29027.

Christelis, D, D Georgarakos, T Jappelli and G Kenny (2021), “Heterogenous results of Covid-19 on households’ monetary state of affairs and consumption: Cross-country proof from a brand new survey”, VoxEU.org, 7 June.

Coibion, O, Y Gorodnichenko and M Weber (2020), “How US customers use their stimulus funds”, VoxEU.org, 7 September.

Cox, N, P Ganong, P J Noel, J S Vavra, A Wong, D Farrell and F E Greig (2020), “Preliminary Impacts of the Pandemic on Client Conduct: Proof from Linked Revenue, Spending, and Financial savings Knowledge”, Brookings Papers on Financial Exercise (Summer time): 35–69.

Crossley, T, P Fisher, P Levell and H Low (2020), ”MPCs via COVID: spending, saving and personal transfers”, ISER Working Paper Collection 2020-14, Institute for Social and Financial Analysis.

Duxbury, D, Okay Keasey, H Zhang and S L Chow (2005), “Psychological accounting and resolution making: Proof beneath reverse circumstances the place cash is spent for time saved”, Journal of Financial Psychology 26(4): 567–580.

Institute for Social and Financial Analysis (2020), “Understanding Society COVID-19 Examine, 2020”, UK Knowledge Service. SN: 8644, 10.5255/UKDA-SN-8644-1.

Jappelli, T and L Pistaferri (2014), “Fiscal Coverage and MPC Heterogeneity”, American Financial Journal: Macroeconomics 6(4): 107–136.

Kahneman, D and A Tversky (2013), “Prospect Concept: An Evaluation of Determination Beneath Danger”, Chapter 6 in L C MacLean and W T Ziemba (eds), Handbook of the Fundamentals of Monetary Determination Making: Half I, World Scientific E book Chapters, World Scientific Publishing Co.

Laibson, D (1998), “Life-cycle consumption and hyperbolic low cost capabilities”, European Financial Overview 42(3-5): 861–871.

Milkman, Okay L and J Beshears (2009), “Psychological accounting and small windfalls: Proof from a web-based grocer”, Journal of Financial Conduct & Group 71(2): 384–394.

Vavra, J (2021), “Monitoring the Pandemic in Actual Time: Administrative Micro Knowledge in Enterprise Cycles Enters the Highlight”, Journal of Financial Views 35(3): 47–66.

Vihriälä, E (2021), “Dedication in Debt Compensation: Proof from a Pure Experiment”, obtainable at SSRN.