Guest: Ben Mackovak is the Co-Founder of Strategic Value Bank Partners, an investment partnership specializing in community banks. Ben also sits on the board for several banks.

Recorded: 1/10/2024 | Run-Time: 1:03:42 ![]()

![]()

Summary: It’s been a wild ride lately for the banks. 2023 was the biggest year ever for bank failures. There are concerns about commercial real estate risk in the banking system, the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates at an incredible pace, and valuations for the entire sector are at a steep discount to the market. So, we had Ben join us to talk about all of this and share if these concerns are justified or if there is still opportunity in the space.

Comments or suggestions? Interested in sponsoring an episode? Email us [email protected]

Links from the Episode:

- 1:22 – Welcome Ben to the show

- 2:08 – Overview of Strategic Value Bank Partners back in 2015

- 5:40 – Distinguishing between community and regional banks

- 7:42 – Discussing bank failures and reforms

- 28:49 – The state of banks today

- 33:13 – Banks exposure to commercial real estate risk

- 35:58 – Engaging with banks

- 40:13 – The impact of fintech

- 49:35 – Revealing Ben’s most controversial viewpoint

- 54:02 – Ben’s most memorable investment

- Learn more about Ben: Strategic Value Bank Partners

Transcript:

Meb:

Ben, welcome to show

Ben:

Meb, I love the intro music. Thanks for having me.

Meb:

Man, it’s been, what, almost a decade now. I feel like we should change it at some point. And the biggest complaint we get is, “It’s too loud.” I said, “Good, it’ll wake you up, get you pumped up, ready to go talk about banks.” Where do we find you today?

Ben:

I’m on the North Coast. I’m in Cleveland at our office.

Meb:

Nice. We are going to do a super deep dive into all things banks today, which is a topic that was like forefront of the news. The news cycle is so short now, it was like the most intense story of 2023, but faded away after a couple of months. You guys have been around since 2015. Tell us a little bit about that period.

Ben:

It seems whenever I try to go out of town, something happens. And so in hindsight, I probably could have predicted all this when I booked my trip to be out of town. So that week you had the Silvergate failure, which happened a few days prior. And that’s an odd little crypto bank, okay, that’s not really a big deal. But then you started to see real extreme volatility in the public market. And so I was at a Hilton hotel in Orange County when all this stuff started unwinding. We had a big private investment, the biggest investment we’d ever made, that we were exiting it and it was supposed to close on that Friday. So Silicon Valley Bank fails and we’re waiting for like a $100 million wire to come in and it turns out that the wire was supposed to go through Signature Bank. And with all the chaos that was going on, they didn’t send the wire. We’re like, “Oh crap, is this still going to… Are we going to have problems here? Is this really going to close?” So March 10th is the Friday, that’s Silicon Valley fails.

Meb:

By the way, I get nervous when I send a $200 wire, I mean a $100 million wire and it not arriving, was that a pretty pucker moment for you? I mean was this a real stressor? Were you able to get people on the phone?

Ben:

It was absolutely a stressor, yeah. Our operations people were trying to track it down and we were talking to the buyer and trying to figure out, “All right, what’s happening?” And they said, “Okay, we can’t send it today. We’re going to pick a different bank. We’re going to route it through First Republic.” That was the backup plan. Friday, Silicon Valley fails. And what people sometimes forget is that the stock closed at $100 the day before. So a lot of times when a stock goes to zero, you have sometimes years to sort of see the problems brewing and if you have a stop-loss or whatever, manage the risk of that. But when a bank is taken overnight, it’s hugely destabilizing because the stock price went from 100 to 0 literally before the market opened. And that freaks people out obviously. And what that does is it makes it harder for equity capital to go into the banking system.

And at this point there’s real concern about a contagion. Are we having 1930 style bank runs? Is this going to be a systemic thing? Because at this point you’ve had three banks fail, but they’re all odd banks. They’re all kind of doing weird things with weird balance sheets. Silvergate was a crypto bank, Signature was a crypto bank, Silicon Valley, who was kind of a bizarre non-traditional bank. And so at the time, I was serving on five bank boards for different community banks across the country and called five emergency ALCO, asset-liability committee, meetings for that day. And an all hands on deck, “What are we seeing boots on the ground? Are we positioned for this? Do we have enough liquidity?” And what became evident is that these bank runs really were not impacting the smaller banks. They were impacting this handful of kind of odd banks that had either concentrated deposits or kind of nichey type business models, and then they were impacting some of the regional banks that were typically catering towards larger business customers. But they really weren’t impacting the smaller community banks.

Meb:

Can you explain the difference for the listeners of when you say community and regional, what are the differentiators? Is it just size of assets? Is it focused on what they do?

Ben:

Typically size of assets. I’d put them into three buckets. You’ve got the big money center banks, the too big to fail banks, and that’s Chase and B of A and Wells Fargo. And then you have the next level that I was on CNBC last year when this was going on, I called them the maybe too big to fail banks. These are the large regional banks that are really, really important parts of the economy. And so in that category, I’d put US Bank, Regions Bank, Fifth Third, Zion Bank, KeyBank. So these are massive banks, but it’s not quite clear if they’re too big to fail or not.

Typically, if you’re big enough to do business with that kind of bank, then you’re big enough to do business with the money center bank. And so people during this time were saying, “No, to hell with it, I’m not going to take the risk that there’s some problem, I’m just going to move my money over to too big to fail bank.” And so it did create deposit outflows in those banks. I think this is probably a larger problem in terms of what I view as a two-tiered banking system in this country where you have too big to fail and then everybody else and it’s created an uneven playing field, which in normal times isn’t a big deal, but in times of stress and panic, it really is a big deal because the money flows to these too big to fail banks and comes out of the community banks and the regional banks.

Meb:

Let’s stick on this topic for a second because there’s a lot of misinformation. Some of my VC buddies who’ve been on the podcast as alums were losing their mind on Twitter that weekend, probably not helping things. But you mentioned FDIC and the process, which is a process that has been very well established over the years. Bank failures are not something that is totally uncommon. It happens. Talk a little bit about the process, why people were going nutty and then also you mentioned reform. What are any ideas on how to make this better if it needs performing?

Ben:

So something that I think people might find surprising is in 2023 there were four bank failures. There was one small one, but it was kind of fraud related in the summer, but there were four bank failures as part of this March Madness thing. Those four banks were combined larger than all the banks that failed in 2008 and 2009. So there were 165 bank failures during those two years, but they were smaller banks, whereas these were really huge banks and combined were actually larger than all the banks that failed, not during the entire financial crisis, but in 2008, 2009.

No bank is really designed to withstand a run. The fractional banking system, you can’t ever set up a bank where all the money could fly out the door in a day. If you lose 30% of your deposits in a short period of time, you’re basically on life support and if you lose 50%, it’s a death sentence. And so that’s what happened. That’s why Signature, Silicon Valley and First Republic failed because they did lose a huge amount of their deposits. Now what made those three unique is that they terribly mismanaged their asset and liability, their interest rate risk, their balance sheet. We focus on net interest margin, which is the margin the bank earns after paying its depositors. And a good net interest margin is 4%. Right now, probably 3% is more the norm because of the pressure on deposits in the last year. But even before that, these banks were running net interest margins below 2%. And because it’s a thin margin business to begin with, going from 3% to 2% is a huge deal.

So when those deposits left, a normal bank could have gotten wholesale deposits or broker deposits or there’s the Federal Home Loan Bank, which will lend deposits to banks. But at the time they would’ve had to pay 5% on those deposits and their assets were earning 3% or 4%. So that was the issue, is they had upside down balance sheets because they had just so mismanaged their interest rate risk and they were working on such narrow margins. So there were some other banks that were near death, PacWest, California, you might know them, Western Alliance, also in California, they’re in Arizona as well. They had probably another 100 basis points of margin, so they had more margin to work with, whereas the other three, there was no way to navigate it.

So I don’t think there was any conspiracy here or anything else. It was just these banks really messed up their balance sheets. And then the Fed had created this perfect storm where they flooded so much liquidity into the system following the pandemic and there was no yield anywhere and certain banks thought that the excess deposits were just going to be there forever, and so they bought long-dated bonds that were yielding hardly anything, never expecting that the Fed would tighten at the fastest pace ever in our history in terms of the number of rate hikes they did in the amount of time they did. So I think that ultimately led to why those banks failed.

Meb:

Do you think in those cases it was sort of an own goal, soccer term, where you score on yourself, where how they manage their interest rate risk, do you think it’s something that actually, given the path of interest rates, it was just inevitable that some banks failed? I mean, I think a lot of people look at the path of interest rates and are actually surprised more banks didn’t get upside down or in trouble.

Ben:

These banks were outliers. Not only did they screw it up, they really, really, really screwed it up. So for sure, it was a known goal. However, the environment could not have been worse for basically what the Fed did over the two-year period. And first off, you had basically quantitative easing 0% interest rates for a very, very long time and that kind of conditioned people, created this muscle memory to just expect ultra-low interest rates in perpetuity. And then you have the Fed and the government just flood the system with liquidity and there’s nowhere to put these excess deposits. And so they buy what they think are risk-free securities.

There’s that saying that generals always want to fight the last battle. And I think the folks running the banks today are, for the most part, the same people that were running the banks in the financial crisis. So it is an old industry. You don’t see people graduating from Harvard Business School going into banking. It’s a lot of the same people and they have that scar tissue from the financial crisis. But people do not want to make credit mistakes because that’s how they got hurt in the financial crisis. And so I think people thought they were being prudent because they were buying risk-free securities. They just did it in a manner where it backfired on them. And Meb, if you go back, I think it was January of ’21, maybe ’22, it’s kind of-

Meb:

Blurring at this point? I hear you.

Ben:

Yeah, the inflation rate was 8% and they didn’t hike rates. You had 0% interest rates and quantitative easing going on, and the CPI was at 8%. And so that’s the way, if we’re going to just hyperinflate and debase the currency, that’s what it looks like. But then the Fed got religion about inflation and so it went from not a problem, not a problem, not a problem to then boom. They just shock the system so quickly that banking is a spread business, it sort of takes time for the assets and the liabilities to normalize, and so you just caught a handful of banks offsides.

Meb:

Got it. Is there any sort of postmortem on this? You mentioned FDIC reform. I think the first thing a lot of people learned very quickly, particularly my friends in NorCal, was this concept of where you keep your safe money, not just for individuals but also for corporates, how you manage payroll. Does it make sense to have $10 million in a checking account at one bank? What do you think about it? You mentioned reform. Any general thoughts?

Ben:

So the week after Silicon Valley and Signature failed, I went out to DC and I met with I think five congressmen that were on the House Banking Committee and one senator who’s on the Senate Banking Committee to talk about this because nobody thinks about this stuff right now or two years ago. You only think about it when you’re in a crisis. But it really showed what an uneven playing field there is when it comes to the too big to fail banks versus everybody else. And in a panic or in a crisis, people say, “To hell with it, I’m not going to worry about this. I’m just sending my money to B of A.” My view is it’s not necessarily good to consolidate all the power, all the credit creation, all that into three or four money center banks. I think the community banking system and the regional banking system have been an important driver of economic growth in this country.

The reason community banks exist is that there’s a lot of small businesses that need loans, need credit that Wells Fargo is not going to screw around with. They’re just too small. And so if you do nothing and all the deposits over time just flow to these too big to fail banks, you’re going to have fewer and fewer regional banks and community banks. And we’ve seen ,what if the banks say you can’t lend to firearm companies or you can’t lend oil companies? Or who knows what it’s going to be next year, next week. So I think having a more diversified banking system is a good thing for the country. So that was the message I was trying to communicate. I made zero progress. All they said, every one of them, “Not a fan of a bailout, this sounds like a bailout.”

And I’m a free market libertarian guy. I’d argue changing FDIC insurance would not be a bailout. The shareholders still suffer, the bondholders suffer, executives lose their job, all that stuff. We’re talking about deposits that people have already earned and already paid taxes on. They’re not speculating, they’re just trying to store their money. And so what I was proposing is a temporary guarantee of all deposits because if you think about it, all of your B of A money is effectively backstop. It’s too big to fail. You’re not going to lose any of your money that’s at Bank of America. The next level down, you really don’t know that. And so then the limit goes to $250,000 and there’s very few businesses that can run on $250,000. It’s just the reality. It hasn’t been changed in I don’t know how many years. It’s not tied to inflation. They just picked that number I think maybe in 2008 or 2009, and it’s just stayed there ever since. And it’s nearly impossible for a bank to scale up getting $50,000 deposits. You really need big chunky deposits for a bank to scale up.

And so what my argument was is you have these too big to fail banks that are paying into the FDIC fund on the 250, but they’re getting the other $10 million basically freely insured. Whereas you’ve got these community banks paying the 250 and then not having any excess deposits because everyone’s worried that anything over 250 is going to get locked up or disappear if the bank fails. And so that was the gist of it, but there was zero interest. And so I quickly figured out that there was going to be no FDIC reform, no calvary riding to the rescue on this. It was a very political topic.

I think some people wanted to blame the San Francisco Federal Reserve. Some people wanted to blame short sellers, as crazy as that is, people were saying, “Oh, it’s those short sellers that cause these bank failures.” So I think the FDIC reform I’d like to see is a leveling of the playing field. Either you break up too big to fail. I don’t see how that happens. The original sin was allowing too big to fail to become it in 2008. But if you don’t do that, then I think you need to do something to address these smaller banks that are trying to compete with those larger banks.

Meb:

Well, right. The crazy thing to me was when all this went down, and I had a tweet that unfortunately went very viral where I was like, “Look, you essentially guaranteed the assets of Silicon Valley Bank.” They came out and said, look, these are money good. And I said, “Okay, well look, that’s all well and fine. You did that. As I think you probably should protect the depositors. But you can’t selectively do that. You can’t now be like, “Oh, you know what? We’re going to do this for this one, but these next 10 that happen, they happen to be in a state nobody cares about, so we’re not going to do it in those.” You have to then protect all of those.

And it doesn’t seem, in my mind as an outsider, to be that hard. It seems like you could either A say, look, if you got safe segregated money with FDIC Infinity, maybe you just segregate that money and say, “Look, this is not ever going to have the risks that might be applied to the rest of the bank”, whatever the mechanics that is. Or you simply say you charge a little more for insurance. But what you can’t do is protect this tech bank with all the perception of it being a tech and VC handout and then let some bank in Kansas or South Dakota or somewhere else fail and just be like tough darts. You should have known better at 250 grand. Because that to me seems like a really foolish way to go about it.

Ben:

The irony is that it’s cheaper to prevent a bank failure, cheaper for the FDIC to prevent a bank failure than to have one. So if they had just done this, it would’ve stopped it right there. There wouldn’t have been any bank failures to backstop because the people would’ve stopped freaking out and pulling their deposits, which was another perverse thing. It was like, why wait until the bank fails to make the deposits money good? If you proactively do it, then you just put out the fire and there’s no reason to do it. I learned early in my career, the market hates uncertainty. When there’s uncertainty, you’ve got to price in tail risks of really different outcomes, and that’s when you see huge volatility. And in banks it’s really dangerous because it can impact the consumer demand.

If Nike’s stock price goes down by 50% tomorrow, I’ll still buy my shoes today or tomorrow. I don’t care what the stock does. If I want the shoes, I’ll buy the shoes. If you see your bank stock go down 50%, you’re thinking about pulling your money, “What’s wrong? Someone must know something, there must be something wrong.” There’s more of a reflexive nature with the bank stock price impacting consumer perception, consumer behavior, and it can create a death spiral. So it’s not something to fool around with, would be my opinion. Because the customers of these banks are not, for the most part, billionaire hedge fund speculators. They’re like small businesses and people that are trying to make payroll, trying to pay their suppliers. That was a wild time. It was certainly stressful.

This is kind of funny to go full circle on too big to fail. The buyer eventually opened an account at JP Morgan and sent the wire through Chase, too big to fail, and the money did show up and then we were able to play offense with it. It was a big injection of cash force and we were able to put that money to work primarily in these regional banks that we were talking about, that may be too big to fail. At that point, we’re down 40 or 50%, we’re trading at six and seven times earnings, huge discounts to their tangible book values. While it’s no fun to go through, that kind of turmoil creates opportunities and that’s just the way investments works. And I’ve done it, I don’t know, 10 different times now, and it’s always very unpleasant to go through, but when you look back you say, “Wow, I would not have had those entry points or those opportunities if not for the chaos, whatever disruption occurred in the markets.” So it did end up being a good opportunity for us despite a tough couple of months.

Meb:

Well, tell us about you guys. So you got started, Strategic Value Partners, 2015. I believe you do both public and private. Tell us a little bit about you guys.

Ben:

There’s real structural reasons why what we do makes sense, in my opinion. Community banks, for the most part, are a very inefficient asset class. Our counterparty, the other person on our trade is typically just some local guy in the community. It’s an attorney or a car dealer, somebody who lives in the town and likes the bank and he’s buying or selling. There are not that many institutional caliber players in this space. And the reason that is is because there’s a lot of regulations regarding ownership, share ownership of banks, and I think they come out of prohibition because I believe the mob used to get control of banks and then use that for laundering money. And so the Federal Reserve when it was formed, made it very difficult for entities to buy banks unless they are banks themselves. And that’s a very rigorous regulated process. We would never want to be a bank, no private equity firm or hedge fund would ever want to be a bank.

And so what that does is that limits your ownership to about 10%. You can sometimes go up to 15%. It is a long, long process. Last time we did it, it took six months to get approved for it. And then at 15%, that’s the end basically there’s another… Well, you can go up a little bit more, but it’s even worse than the application to go to 15%. So for the most part, institutional investors will stay below 10%. And what that has done is it’s kept Blackstone, KKR, Carlyle, it’s kept traditional private equity out of this area because they don’t have control, they can’t take the bank over and run it. And it also is nice, and this is the part we don’t say out loud, but it creates less pricing competition. So if there’s a bank that is going to sell 20% new equity and it’s between us and another firm, we can only both buy 10%. There’s no need to kill each other over price to go buy the 20%. And so I think it creates just less competitive pricing because people get capped out with their ownership.

I’d say there’s three ways to win. The first is multiple expansion. That’s easy. That’s just traditional value investing. You buy it cheap for some temporary reason, some misperception, whatever. At some point the valuation multiples are typically mean reverting and the market at some point will re-rate it higher, you’re going to make a return on that. Okay, that’s great. A lot of people do that. The second way to win is through organic value creation. So the day-to-day operation of the bank. So taking in deposits, making loans, getting paid back. Over time, a well-run bank should be able to earn a return on equity of let’s say 10 to 12%. And so over time, if nothing happens and they just keep running the bank, the earnings per share should grow, the tangible book value, the book value should compound and the dividends should grow. Some combination of those three things should happen if it’s being run in a safe and prudent manner. So that’s the second way.

And then the third way is through M&A. And M&A is an important way to I guess unlock value. Consolidation in the banking industry is a 40 plus year secular trend. It’s been going on for a long, long time. There used to be 15,000 banks in the country and today there’s 4,000. And if you look at Canada or Europe, there’s just a handful of bigger banks. So consolidation, there’s a lot of benefits to greater scale in the banking industry. And so there’s a lot of reasons why consolidation has occurred for a long time and why it should occur. And so that’s the third way we win is at some point our banks are hopefully attractive to a strategic buyer, and we can get into some of the things that make them attractive or not attractive, and we’ll merge with another bigger, better bank and that will unlock value for us.

Meb:

So you guys started out I believe public markets and then do private as well. Correct me if I’m wrong. But tell me a little bit about the metrics or what you’re looking for in publics and then what led you to privates, and are the metrics similar? Are you just buying low price to book or how’s it work there?

Ben:

It really is where the opportunities are is what we focus on. And when we first started, there was a lot of opportunity in the public markets. The public market valuations were basically the same as what was getting done in the private market. And so if the two are equal, you’re better off in the public market because you have liquidity and typically they’re bigger and more sophisticated, more resilient banks. When Trump won in 2016, the banks jumped about 30%. So the multiples expanded by, let’s call it, 30%. But what we noticed was the private market didn’t really change, the deals that were getting priced at 110 of book value were still getting priced at 110 of book value. And so that’s what led us to launch our second fund, which had an emphasis on the private.

Fast-forward to March of 2020, the pandemic breaks out and the market goes to hell, the banks go to hell, all private deals just stop. We’ve seen this a couple of times, that the market just freezes, there’s nothing to do. And the thing about the public market is it’s always open. So it really shifts based on what the opportunity set at the moment is. There’s 4,000 banks in this country, so there’s always somebody who’s doing the right thing trying to make money for shareholders, and our goal is to find them and try to partner with them.

We have some investments we made on day one that we’ve owned for eight plus years. So it’s not necessarily that we’re going to get in there and tell the bank to sell itself. That’s not the case at all. A lot of times the bank and the board are the ones that initiate this for succession planning. So I mentioned, banking in general is an old industry. A lot of times there’s not a number two successor at these banks and M&A is how they address succession planning. As I mentioned, there’s a lot of cost synergies in banking and a lot of benefits of scale. And so we have a chart that I think is in that deck that I shared with you that shows the return on assets based on a bank size. And there’s a very linear function that the bigger the bank gets, the more profitable it is, the more it makes that flattens out at around 2 billion. But there is huge benefits to scale from zero to 2 billion, which also encourages a lot of M&A activity.

Meb:

Interesting. So give us an overview of 2024, and you can take this in every way. What does the opportunity set look like to you in publics, in privates, and then pivot into what does some of the bank insight give you as a look around the corner into the economy? We can take it anywhere you want, but we’ll touch on all these at some point.

Ben:

When originally we had talked about doing a podcast, I think somebody had canceled back in October. The banks are up 30% since then. So there’s been a big run in just a couple of months.

Meb:

Should have had you on. What happened, man? All right, next time we’ll be more timely.

Ben:

Yeah, they’re not nearly as cheap as they were, but I certainly wouldn’t call them expensive. Right now, the banks trade at about 10 times earnings S&P’s at 19 time earnings. So they’re still not what I would say expensive, but they’re not as distressed as they were. What I think could surprise some folks is you’ve had this rapid rise in the cost of funds for banks. That’s what they have to pay their depositors.

In Q3 of 2022, the cost of funds for the whole industry with 66 basis points. In Q3 of 2023, we don’t have the Q4 numbers yet, it was 244 basis points. So that’s a 4x increase in 12 months. That’s really tough for the industry to handle in that period of time. On average, the cost of funds for the bank sector is about 70% of what the Fed funds rate is and it takes some time to kind of normalize there. I guess the cost of funds for the industry was way too low in 2022. And so a lot of people think that the pressure on deposits started with Silicon Valley and First Republic and stuff, and it didn’t. It really started in Q4 of 2022. There was a big jump in deposit rates. And then it continued in Q1, which was basically the spark that lit the fire.

That was a function of if you could get higher yields and money market funds or in Treasury bonds, what are you do in keeping your money in a bank account? Getting nothing for it? And I think people had been so conditioned because of 10 years of 0% interest rates and quantitative easing and all this stuff that they just got lazy and kind of forgot about managing cash. It wasn’t really a priority or an emphasis. So what is interesting, in December of last month and now this month I’m hearing of some banks cutting deposit rates by 10 or 25 basis points. So you’re finally seeing the cost of funds pressure in the industry diminish and you’re seeing those rates go down.

So what I would expect in 2024 is that the net interest margin that we talked about has been getting compressed and compressed, that it either bottoms in Q4, which we’ll get those results in a couple of weeks or Q1, and then at that point when you see net interest margin expanding… Because banks have been putting on loans at 8 and 9% for the last six months. So the old stuff’s rolling off, the new stuff is priced appropriately and then now you’re seeing deposit costs roll over, that should lead to margin expanding, which means EPS will be going up.

The other thing, and I don’t know if you or your listeners how much you guys have looked into all this, but this term AOCI, it’s the mark to market bond losses in their portfolios. So it’s other comprehensive income. What it has done, it has depressed tangible book values for the banks. And I’d say there are a bunch of banks out there that have their tangible book values that are 20 to 30% understated because of these mark to market losses in their bond portfolio. And bank stocks typically trade on a combination of price to earnings or price to tangible book value. And so when Q4 results come out, because interest rates have come down so much recently, you’re going to see those AOCI losses shrink, which will result in much higher tangible book values I think the market is expecting. So I think those are the catalysts, is that you’ll have net interest margin expanding, AOCI losses going away and they’re still relatively cheap.

Meb:

So when you’re looking at banks, are there any hidden landmines? As I think about this, one of the biggest exposures for a lot of banks is they write a lot of loans for whether it’s local commercial mortgages, thinking about malls, places people no longer go to, offices. Are there any concerns that are real or unfounded in that world or anything that you’ve kind of been interacting with them over the last few years that worry, not worry?

Ben:

There’s a lot of doom and gloom out there about commercial real estate, and maybe people think I’m talking my book, but I really think the commercial real estate fears are overblown. As I mentioned, it’s a lot of the people who were around in 2008 are still running these banks. And in my opinion, the underwriting standards have not degraded. People learn their lesson. I think those fears are probably overblown. Office is absolutely a mess. So no doubt about that. But I would point out that most of that exposure is not in the banking system. A lot of it’s at REITs, insurance companies, pension plans, private equity, private credit funds. So while I wouldn’t want to own an office tower in San Francisco-

Meb:

Can get them for pretty cheap these days. I’ve seen some of the prices down on Market Street. Not too bad. There’s a price you might want to own.

Ben:

I think that’s right. I think there’s no bad assets, there’s just bad prices you could pay. So at some point it would be a good investment. But from a bank standpoint, as we think about credit losses… Because that’s how you lose money investing in banks is credit problems. It’s a narrow margin business, so if you have credit problems, that’s going to create an investment problem as a shareholder. I would say that the underwriting standards probably are much better now than they were pre-financial crisis. So I don’t see a systemic issue in terms of commercial real estate as a big landmine.

Now if the economy goes into a recession, for sure there’s going to be credit problems. But if you’re investing in banks that have reasonable underwriting standards, there should be a lot of margin of safety because when they make the loan, they’re requiring equity upfront. Office is its own beast. So let’s take that out of the equation. But other real estate has appreciated in value since the pandemic. So your equity or your margin cushion has expanded even more. You could probably see a drawdown of commercial real estate values at 30% and the banks still wouldn’t have any losses because there’s that much equity built into them. So I think the system overall is in much better shape than it was before the financial crisis.

Meb:

When you’re looking at the privates, I was thinking this, how do you source these banks? Is there enough public information? Or is it a process that is not public? And then how do you get them to accept your investments? Do you guys say, “Hey, look, we got some value add we can give you”? How does that whole process work? Because different than startups in my world where everyone’s always looking for money. How do you go about getting info and how’s the whole process work on the private side?

Ben:

So we’re nine years into this and $500 million at a UM, in the scheme of things, not a big player, but actually a big player in this world. There’s only a handful of folks that do this with an institutional caliber platform and balance sheet. And so we have been able to develop a good reputation in the industry and our goal is to help our banks become bigger and better. It’s as simple as that. And so we want to be more than just a source of capital but also a strategic resource for them. And that’s why a lot of times we join the boards. I’ve been on nine bank boards, I’m probably going on number 10 in a couple of weeks. That’s the model that we’re trying to implement.

In terms of coming in, sometimes it’s through a capital raise, so if they need to raise growth capital or they want to expand into a new market or they want to do something and they need more equity capital to do that. Other times it’s a balance sheet restructuring and we haven’t really had those lately because there haven’t been credit problems. But if a bank needs to write off bad loans, they need to bring in new capital. So that’s the bank bringing in new capital that would come from us from people we know in the industry. There’s a handful of investment banks that specialize in just raising money for banks. The odder situation is where we buy existing stock. And we’ve had some bizarre ways of getting in over the years. And so there aren’t that many people who can write a 5, 10, $20 million check for a privately held community bank. That’s just not on a lot of people’s radar is what they want to do with their money.

Meb:

And do they tend to use it for liquidity for owners or is it more for growth?

Ben:

When the bank is doing it, it’s usually for growth. But sometimes there’s existing owners who want to get out, who need to get out. And so there were two brothers in North Carolina, I don’t think they were Fabers, but they were going to prison for some white collar crime and they wanted to get out of this stock that they had owned for a long time. And so we negotiated a deal with them, we viewed was an attractive entry price. And the bank had nothing to do with it. These guys had done something totally unrelated. But that was a situation where an existing shareholder needed liquidity. If you’re the only one that shows up at the table, typically you can negotiate pretty good terms. There was another guy in Colorado who had to file for bankruptcy. He owned big stakes in two community banks. We ended up striking a deal with the bankruptcy court to buy his stock. We’ve had family disputes where there’s some family fallout and somebody wants the money and never to talk to the family members again, so we’ll come in that way. All sorts of just one-off things.

The nice thing about the banks is they’re highly regulated and they’re required to file quarterly, they’re called, call reports with the FDIC. If you think about you and I could start an unregulated bank tomorrow and nobody would show up. The secret sauce is really the FDIC insurance that’s saying, “The money I put in this bank is protected.” And complying with that is what allows banks basically a cost of capital advantage because they fund themselves with deposits that are anywhere from 0% to 3% or 4%, but in order to keep the FDIC coverage, they have to file call reports. And so even small private companies in the middle of nowhere have to file effectively structured, clean financial data each quarter. And so a lot of times if it’s a truly private company, we’ll work off of that in conjunction with any of the financial reports we get from the actual company.

Meb:

And we’re jumping around a little bit, but I keep thinking of different things. What’s the state of FinTech disruption in this world? Are they somewhat immune to it because of the community nature to it? Or some of the VCs love to try to disrupt traditional industries that have nice profit margins and our world tends to be one of those. What is the pressures you’re seeing, if any, on your portfolio companies, both public and private?

Ben:

This might be a little contrarian for any of your VC listeners, but I think this FinTech disruption idea for the banking system is overblown. If you go back 20 years ago, people thought that the internet banks were going to make traditional banks obsolete. You have an internet bank, there’s going to be no more banks anymore. Well, that didn’t happen. There is still a need for credit creation for small businesses in this country. If you think about how a community bank can keep up with technology, it’s actually not that hard. None of them have programmers or R&D, they buy their tech, they buy their software from their core system provider and there’s like four or five of them, Fiserv is one, Jack Henry, FIS.

So they’re these bigger companies that provide the software and the technology to basically every bank in the country. And so it’s those companies that develop the new stuff that do the R&D and they buy, acquire a lot of upstarts. If somebody comes up with a great loan underwriting platform or mobile banking app or something, typically these companies will either reverse engineer it or they’ll buy it. And then they roll that out to all their community banks.

So in 2024, if a community bank doesn’t have mobile deposit app for your phone or some of these things, it’s because they’re not trying. This stuff is readily available and cheap to everybody. And so that idea that it’s going to render them obsolete, I don’t know how that happens because they really just adopt it and they adopt it at scale because it’s coming through these other scale providers, they’re not developing it themselves.

I don’t think FinTech is that big of a deal. What I think could be an interesting opportunity is harnessing AI for maybe credit underwriting, loan underwriting, credit pricing. So that to me seems like that’s a very manual process, it requires a lot of people, it’s still kind of messy. To me that could be a real opportunity for the industry is you would use less people and have better data and be able to make better decisions. I’m convinced that there’s a ton of margin left on the table, that banks for the most part will say, “I’m going to make you this loan at 8.5%.” And the customer will say, “Well, the other bank said they’d do it for 8%.” And then the bank goes, “Okay, we’ll do it for 8%.” That’s like how it works. And if you had better data, you could say, “No, the rival didn’t offer 8%, but we’ll give you 8.40.” And that’s just free margin right there that would all drop to the bottom line. So I think there’s probably some opportunities for AI to make the banking sector more efficient.

Cryptocurrency, I don’t know. I’m still waiting for that to be a viable payment system. I don’t know what the big solution without a problem or something like that. I can send wires, I can send Venmo. I don’t see how a cryptocurrency can really be used for payments. It’s too volatile. It’s not a store of value. It’s not easy to transact. Banks have been around a long time and I think they’re going to continue to be around a long time. I think there’ll be fewer of them, and I think they’ll be bigger. If you don’t go to the branch and get cash, that’s not really good for a bank.

If you think about why a bank exists, how it makes its money, it’s not, “Oh, I never go to a bank branch anymore, so my bank is obsolete.” No, it’s someone to hold deposits, so store your money, and then if you need credit, it’s someone to extend you credit. That’s how a bank makes money. It’s not, “Well, I don’t go into the bank to change my quarters anymore.” For sure, it’s less branch activity, but I don’t know that it makes the banks any less relevant in terms of the true fundamental drivers of what creates profitability for the banking sector.

Meb:

As you kind of value and think about these banks, is there any ways that traditional investors try to value them that you’re like, “Oh no, you should totally not do that”? Is there anything where you hear analysts come on TV and they’re talking about banks where they get wrong?

Ben:

I’ve heard people try to talk about EV to EBITDA is a multiple. That doesn’t make any sense. I’ve heard people talk about more FinTech banks, I won’t mention any names, but on a EV to sales multiple, that really doesn’t make any sense. So I think at the end of the day, the ultimate judge of value is sort of the industry itself. And when a bank acquires another bank and values another bank, it prices it on an earnings multiple and a price of tangible book multiple. They kind of act as a governor on each other. So neither one can really be out of whack, if that makes sense, because banks don’t want to dilute their own tangible book values over time.

So we’ve looked at a lot of studies on bank stock correlation and banks over time trade with trends in earnings per share and tangible book value. And so if those are going up, over time the stock price goes up. If those are flat, over time the stock price will be flat. If they’re down, the stock price goes down. And so it’s really kind of as simple as that in terms of valuing them. They’re all different, but there are a lot of similarities too with the banks. It reminds me of the Tolstoy line, “All happy families are alike. Each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” It’s really true for the banks. They’re similar businesses, but they’re all, either it’s their market or their focus or their management, there’s kind nuances that if done right can create value and if done wrong, can destroy value.

Meb:

You mentioned holding some of these private companies for like eight years. What is the liquidity option as you get out? Are you generally have provisions where you’re selling it back to the bank? Are you finding M&A transactions? How does that go down?

Ben:

M&A is a really important part of our strategy. It’s often the catalyst that unlocks value and also creates liquidity. And Charlie Munger would talk about the Lollapalooza effect. And so if we invest in a bank, and I’m just going to use generic numbers, but let’s say it has a $10 book value at the time and we pay one time book value for it, we come in at 10 bucks, and over a period of time they double that and it’s now a $20 book value. And instead of it being worth one time, it gets bought out at one and a half times. So that is a $10 investment, but because you get the big multiple expansion on the higher book value, that’s how you can generate a nice return over time. So M&A is really, really important for us. ’23 was a terrible year. M&A activity was down 60% year over year. And I mentioned that bank M&A is a long-term secular trend that’s been going on for 40 plus years.

Meb:

What’s the driver there? Why have things slow down so much? Is that just the general, everything kind of slowed down?

Ben:

No, it’s because of what happened in March and April. Bank consolidation, it just happens for a bunch of different reasons and we can get into them, but they’re kind of nuanced. But during the financial crisis, it stopped. During the pandemic, it stopped. When there’s a disruption, M&A just comes to a grinding halt.

Meb:

Makes sense.

Ben:

Yeah. And so ’23, deal count was down 60%, pricing was probably down 30%. And so for us, that’s a bad thing. Now, typically that’s how we get liquidity is an M&A deal. There’s been times where we have sold it back to the bank where the bank wants to repurchase shares, and maybe we’ve just had a differing of opinions of what they should be doing, or maybe we need the liquidity or whatever. Sometimes we’ll sell it to the bank. Sometimes we’ll sell it to other investors. So there are a handful of other institutional community bank investors like us. The one I mentioned, that $100 million wire we were chasing, that was another private equity firm that was the counterparty on that one.

Meb:

What’s even the universe for you guys? How many names is even in the potential pot?

Ben:

Well, in theory there’s 4,000.

Meb:

Wow. Public?

Ben:

No, no, no.

Meb:

Oh. I was like, “Wait a second. What does that even-”

Ben:

Total banks.

Meb:

Okay.

Ben:

Public’s probably 400.

Meb:

Yeah.

Ben:

Okay. When I say public, that just means they have a ticker. A lot of them are OTC.

Meb:

Okay. And based in Utah and Vancouver. I feel like that’s where all the shady banks, for some reason, to my Utah friends, I don’t know why.

Ben:

You ever watch American Greed?

Meb:

Only when I’m at the dentist or something. When it’s on in a hotel, I turn on the TV and it’s like American Greed is on. So I’ve seen a few.

Ben:

Yeah, it’s like everyone is either in Southern Florida or Las Vegas it seems like.

Meb:

Florida, of course. All right, so there’s the actual pool you’re fishing from, what is it, closer to 50? 100?

Ben:

No, no, 300 or 400.

Meb:

Okay, so decent size. Okay.

Ben:

Yeah.

Meb:

All right. Well, let’s ask you some random questions now. We’ve been jabbering about all sorts of things. What’s a belief you hold, and this could be investing at large, it could also be specific to banks, that you sit down at the Browns tailgate, say it to your professional buddies, so it’s a bunch of bank nerds hanging out or just investing nerds, and you make this statement and most of them shake their head and disagree with? What’s the belief?

Ben:

That’s an easy one, that you can make money investing in banks. I think a lot of people, generalists view the banks as being uninvestable. A few months ago, before this big runup, I had my analyst check the valuation multiples for the banks and compare them to the newspapers, coal companies, tobacco companies, and radio stations.

Meb:

You’re getting some low bars.

Ben:

At the time, only the coal companies were trading at worse multiples than the banks.

Meb:

What causes that to change? I mean, what’s the psychological rerating here? Is it a bear market where a lot of these cash flowing businesses get rerated or what do you think?

Ben:

They just are cyclical. I remember in the summer of 2020, there was a bank fund kind of like us that shut down, and it wrote this long letter to investors that got all over the street, everybody saw it, that said that, “The banks are uninvestable, and as such, were returning your capital.” And guess what happened next? The banks went up 100% in the next 18 months. From when that letter went out, 18 months later, they were up 100%.

Meb:

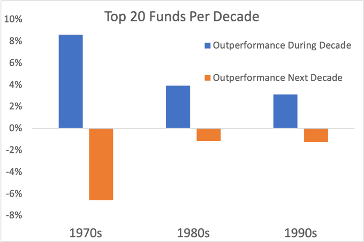

You have a chart in your deck where it looks at bank PE ratios relative to the S&P. And there was a period not too long ago, so let’s call it six years, where banks had a higher PE ratio than the broad market. And today it’s half. So that’s a pretty big discount.

Ben:

Yeah, it’s a huge spread. I don’t want to make excuses for the banks because it’s obviously been a tough road, but I think the pandemic was a black swan event that uniquely impacted the banks. And so that breaks out, we closed the economy, forced the economy to shut down, and then the bank regulators really pressured the banks to put all loans on deferred status. So you didn’t have to pay your interest, you didn’t have to bank your principal payments, and they pressured the banks to do this, that it wouldn’t create cashflow problems for the economy. And so that led to a huge drawdown in 2020. And then you had all the insane monetary and fiscal policy that distorted the yield curve and flooded the system and then caused the problems in March. And so you’ve had two very acute crises in the last three years for the banks.

And it was like we talked about earlier, the Silicon Valley Bank closed at $100 on Thursday and never reopened. And so that’s very unnerving. If you don’t really understand this industry, why are you going to fool around with that? And so I think that drove a lot of generalist investors away from the banks. I went to a bank conference in November and it was bleak. It was kind of every bank bitching about its stock price.

Meb:

It’s a good sign. I like that. I like [inaudible 00:51:14].

Ben:

Yeah, it is a good sign. The attendance was down 30% according to the organizer. All the investors were fully invested. Like if you were going to buy bank stocks, you basically bought them in the spring and into the summer, and at that point you were fully invested. There was no new money coming in. So I think if we get a more normal yield curve, they’re going to be just too cheap to ignore. And I would say that that will cause the banks to rerate. It’s not the 5% Fed funds rate that causes the problem. It’s the 4% 10 year. If that 10 year is 6%, then that’s fine. The banks really just need a normal sloping yield curve, otherwise it’s a spread business and they just pass it through. Inverted yield curve is very, very tough for a bank to navigate.

When we met, Meb, it was November of 2019 at the University of Virginia Darden Investment Conference, and I just pulled up the agenda for it, and I think you were on a panel talking about systemic investing. And we were talking about private credit and quant investing and machine learning. Bunch of smart people. We spent the whole day talking about stuff. Nobody said, “In two months there’s going to be a pandemic that’s going to totally disrupt the whole world.” So I think it’s a little bit of that black swan thing that it really, really hurt the banks. It’s going to take time to bring investors back to them and for multiples to expand.

Meb:

Well said. What’s been your most memorable investment across the years?

Ben:

Well, I believe you always learn more from your mistakes. So even thinking about this last night, I had PTSD going through it. But before the bank fund, before Cavalier Capital, I was at Rivaana Capital, which was a long/short fund in Charlottesville. I recommended we make an investment in a company called USEC which is a uranium enrichment company, and it was privatized out of the Department of Energy in the 1990s. It was an absolute monopoly, impossible barriers to entry. They had this program with Russia called Megatons For Megawatts, and they would get weapons-grade uranium from nuclear weapons, and they’d ship it over, and then they would turn it into low grade fuel that could be used for power plants.

This is in 2010, maybe. People are still spooked about the financial crisis and the recession. This is a beautiful business. There’s no competition, massive free cash flow. It’s not economically cyclical, exposed to the economy. So I recommend it to the PM and gets in the fund and becomes a pretty big investment for us. And I guess the reason why the stock was undervalued, in my opinion at this time, is they were building a new facility that was going to be the next generation enrichment. And they had spent billions of dollars of their own money on it, and they needed 2 billion from a loan guarantee from the Department of Energy to finish it. So a very stable, massively profitable business.

March of 2011, there’s an earthquake in the Pacific Ocean. That earthquake causes a tsunami. That tsunami hits Japan. Someone 40 years prior had built the nuclear power plant in an insane place that was right on the ocean and was prone to flooding. Furthermore, their backup power facility was also either underground or in a low-lying area, that also flooded. So this is the Fukushima incident. And causes that disaster to happen. It totally killed the nuclear industry. You saw existing plants be retired. No new construction come online. Price of uranium collapses. So eventually that company filed for bankruptcy.

The moral of the story is the best investment thesis can be totally upended by some black swan event. And so you just need to have a real dose of humility because you never can predict the future. The future is always uncertain and you do the best analysis and think you’ve got something that’s just a layup, and then the world is way more chaotic and uncertain for that. And so I think that is memorable because it just seared in my memory. We lost a bunch. It was awful. It was embarrassing. But it has really, I already knew this, but really reemphasized just risk control is so, so important. The math behind losing money is so bad. If you take a big drawdown, you’re down 50%. You have to be up 100% to break even. So a big part of successful investing, in my opinion, is controlling risk, avoiding the big drawdowns. I don’t know. Have you ever met Paul Tudor Jones?

Meb:

Not in person, no.

Ben:

I got to know him a little bit. He’d always come down to UVA. And he’s huge on risk control and risk management. That’s something he talks about a lot. You can be wrong a lot, as long as you control the downside. And when you’re right, you need to make multiples of what you lose when you’re wrong. And that’s my investment philosophy boiled down into a nutshell is you really need to focus on controlling risk, understanding what the downside is.

That’s another nice thing about these banks, assuming that they’re not run by total cowboys or fraud or anything like that. If a bank struggles and stubs its toe, there’s typically 95% of the time a bank that will buy it book value. And so there’s some off ramp there that if things do go sideways, there’s typically a buyer who will take it and you probably get your money back assuming that you bought it cheap enough. And I can think of a handful of situations where they didn’t turn out to be the great investments we thought they were, but we ended up either getting our money back or maybe making a little bit. Because there are typically strategic buyers for banks that are up for sale.

Meb:

Well, the uranium story is another lesson. You just got to hold on long enough. 2022, 2023, 2024 has been shaping up to be a pretty bull market for all things uranium. So you just had to buy a basket and go away for a decade. Eventually you’d be proven right.

Ben:

That company filed for bankruptcy. But I guess I just saw this, it’s now a public company again. It’s called Centrus?

Meb:

Buy some just to complete the circle.

Ben:

Yeah, a long history there.

Meb:

Ben, it’s been fun. Where do people, if they want to find more info on your fun, your writings, what you guys are up to, where do they go?

Ben:

I keep a pretty low profile. I guess LinkedIn. We don’t have a website. Maybe for our 10 year anniversary we will.

Meb:

That’s real old school man. I mean, Berkshire at least has a placard, so you guys are even more old school. I like it. Well, Ben, thanks so much for joining us today.

Ben:

Thanks, Meb.