In a previous EconLog post I discuss the origins of ska. But how did we get from ska to ska punk?

Jamaican immigration to England was crucial to the birth of ska punk. Evan Nicole Brown writes that:

In 1948, the United Kingdom opened its doors to citizens of British territories, because it needed a larger labor force to help rebuild its economy after World War II. As a result, West Indian immigrants traveled in great numbers to London, specifically neighborhoods like Brixton and Peckham. By the time ska was born on Orange Street these families were firmly settled in their new place across the pond, so, when the time came, ska music found a home in London, too. Around the early 1960s, the first British-Jamaican sound system was up and running, and British youths started to become exposed to ska music through their proximity to these Jamaican enclaves, which were working-class areas similar to Kingston back home. “They gathered together at house parties because that was their culture, and they missed home,” Augustyn says of the immigrant community.

It wasn’t long before their English neighbors developed a taste for the sound and ethos of ska music, played from the classic Jamaican vinyls booming through the sound systems, and with the growing presence of bands like The Specials, The Selecter, and Bad Manners, ska’s second wave, Two-Tone, was born. “[The British] loved [ska], and then they blended it with what they knew, which was early punk rock,” says Augustyn. This European twist on ska didn’t forget its roots. In fact, Two-Tone bands were known for being diverse, as most usually had one or more Jamaican members. A popular band of this era, Madness, got its name from a Prince Buster song of the same title.

Immigration allows people to associate and learn from people with very different knowledge and life experiences. One result is that they can combine their ideas, creating something new and wonderful. In this case, a genre of music and a scene that brings many people joy to this day.

As economists, we can measure many of the benefits of immigration. For example, a substantial literature on the place premium shows how much immigrants can increase their earnings by moving to a wealthier country. This obviously benefits the immigrants enormously. But it also benefits many other people, because the immigrants are earning more largely because they’re able to do labor that creates more value. This is part of why some economists estimate that abolishing migration restrictions could roughly double world GDP.

However, not all benefits of immigration will be captured in prices. While ska punk may not have come about without immigration, not all ska punk artists were Jamaican immigrants. Even if we were to aggregate all the final sale prices of ska punk records, concert ticket sales, and merchandise, this might underestimate the benefits. While I have purchased all of these, much of my enjoyment of ska happens when I listen to ska music on YouTube or streaming sites. In these contexts, I am receiving substantial consumer surplus relative to what the artist is paid!

Ska punk may not be your favorite genre. But chances are that at least one thing you love, whether it’s a type of music, food, art, technology, or consumer product, is a similar result of the creativity, cultural exchange, and entrepreneurship that immigration enables.

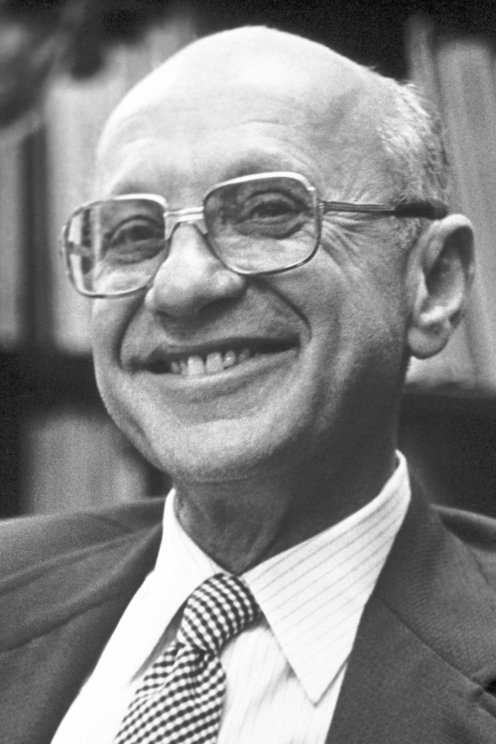

But in recent decades, wealthy countries have been increasingly restrictive of immigration. This hurts prospective immigrants enormously. But it also hurts the rest of us. As Michael Clemens teaches us, migration restrictions leave trillion dollar bills on the sidewalk. When you see a trillion dollar bill on the sidewalk, be an alert entrepreneur and pick it up, pick it up, pick it up!

Nathan P. Goodman is a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Economics at New York University. His research interests include defense and peace economics, self-governance, public choice, institutional analysis, and Austrian economics.