My kids and I began reading banned books together when they were just learning sight words. Snuggled with my kids on the couch, I’d read aloud from a slim paperback volume of the “Captain Underpants” series. My son, 6, and my daughter, 4, followed along by looking at the images.

We giggled through the antics of fourth-graders George and Harold as they conspired against their mean school principal. I’d try to keep a straight face while reading dialogue in a character voice: “Help! Wedgie Woman is in the teacher’s lounge. She just drank all the coffee and now she’s giving the gym teacher a wedgie!”

I’d rather have been reading a children’s poetry book by Jack Prelutsky than such raunchy humor. I’d hoped my kids would learn to love words as I did while listening to the sounds melding together rhythmically as I read them poems, but poetry ultimately failed to engage my kids. Instead, my son was so fascinated by “Captain Underpants” that he began creating his own series of comic books. He spent hours drawing and writing the stories of “Captain Hypnotizing Man” and “Adventures of Super Dog” on plain printer paper, stapling or taping his creations together. Soon, my daughter was also composing and stapling together her own picture books.

This burst of creativity in my home occurred as Dav Pilkey’s series topped the list of books most frequently targeted for censorship in 2012. I didn’t know it at the time, but complaints tallied by the American Library Assn.’s Office for Intellectual Freedom cited offensive language and inappropriate material for the age range as reasons why people requested that “Captain Underpants” be pulled from schools and libraries. These were among 464 complaints lodged against books in the U.S. that year.

Fast forward to 2021, when the library association recorded nearly 1,600 book bans or challenges, the most since the organization began compiling its list more than 20 years ago. “Captain Underpants” was the second most challenged book in the decade from 2010 through 2019. It’s disheartening that a comic book character depicted by a bald guy wearing a red cape and white briefs that cover nearly half his body has inspired so many people to censor books.

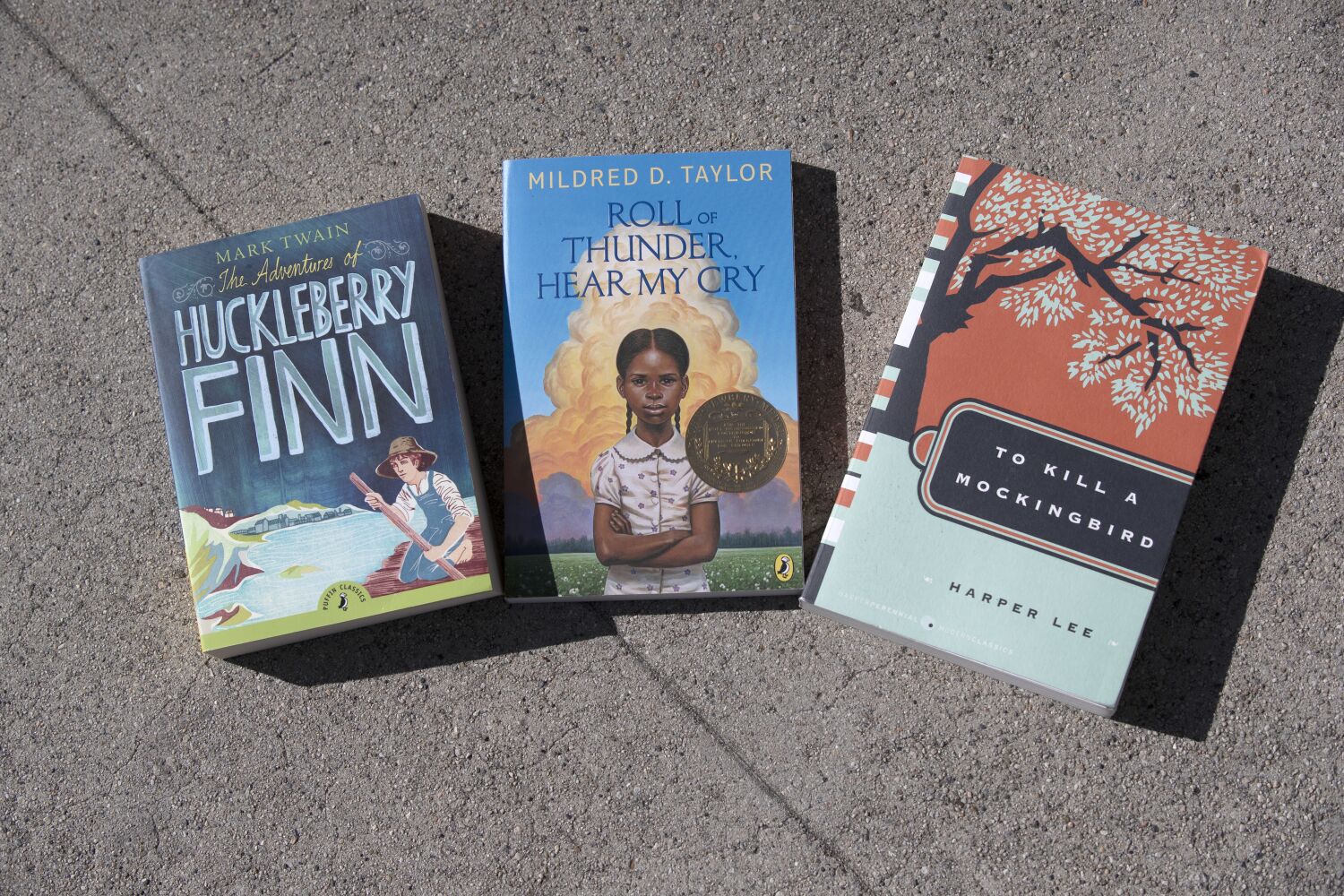

We’d like to think that California, with its many well-regarded academic and cultural institutions, is free from the oppressiveness of censorship. The desire to suppress uncomfortable ideas is found in all communities. In 2020, the Colton Joint Union School District removed “The Bluest Eye” by literary giant Toni Morrison from its list of books that can be assigned by teachers over its controversial subject matter involving rape and incest. The district lifted the ban after six months, instead giving parents the choice to have their kids opt out of reading the book. Controversy over books sometimes arises from overprotectiveness. At the Burbank Unified School District the same year, the superintendent removed five classic novels from the required district reading lists. The books, which included John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men” and Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird,” were still allowed in classrooms and the school library after parents protested that the books were harmful to Black students. The move effectively means that most kids won’t be reading the books.

A few years ago, a parent in my Southern California neighborhood complained on a community Facebook page that a book her kid had borrowed from the elementary school library contained mature themes inappropriate for young kids. She posted photos of book pages. Parents complained. Some demanded that the book be removed from library shelves. One mom offered a sure solution: Report the book as lost, then burn the book.

We parents should realize that we won’t always know which books are best for our kids. I found that out the day my son brought home “Captain Underpants,” a book I would’ve never picked out on my own. Yet these puerile comic books helped my kids develop their reading and writing skills. “Captain Underpants” led to “Magic Tree House” books, which led to the “Harry Potter” series, which led to “The Hobbit” and “The Lord of the Rings.”

Certainly, parents should have the right to choose the books their kids read. But parents calling for books they find offensive to be pulled from library shelves, or to be permanently removed from the curriculum, are claiming overly broad rights. They’re deciding what all kids can read, not just their own kids. And these days, it’s not just parents demanding book bans. Elected officials, political activists and religious groups are also clamoring for censorship.

At least 50 groups nationwide are working on a local, state and national level to censor books, with many of them working together in a concerted effort to remove books about LGBTQ topics or race, according to the nonprofit literary organization PEN America. The books under attack are likely to feature LGBTQ topics or characters, or characters of color. Those harmed the most by these bans are kids who are LGBTQ or youths of color, often both.

What is the learning loss for kids deprived of books that can connect them to the joys of learning? What is the cultural loss for kids who won’t see themselves regularly depicted in books, or see people different from themselves humanized through the art of storytelling? Banning books causes an infinite ripple of losses for society. And often it starts with just one parent, just one book.