Stock Depot/iStock via Getty Images

Investment thesis: While I had many other potential candidates in mind, after pondering for a while, I concluded that the most important investment story of 2023 will most likely be China’s response to our tech squeeze on its own domestic tech sector. I expect China’s response to our technology transfer and use restrictions, meant to create a bottleneck in their high-tech industry will continue to be calm and not overly aggressive in retaliatory moves, which signals to me that they feel confident in being able to overcome our obstruction.

I don’t think that at least for now China will retaliate by withholding crucial rare earth materials, dumping USD-denominated assets, or by imposing tariffs on US & EU goods. It will respond by opting to do what we are forcing it to do, namely reinvent the wheel. It will do it fast, and it will aim to do it better. At the same time, it will continue to tie much of the rest of the world to its own economy. In this respect, I believe 2023 will be crucial because there is a high probability that by the end of this year, we will get to see the contours of that much-improved wheel taking shape, and based on how good it might be, we need to brace for a major shock to our own high tech industries, as well as to our overall economy.

Some runner-up investment stories:

The Ukraine conflict is the main runner-up.

It might be valid to argue that this will be a much larger story for investors to follow in 2023 because arguably it has a far more immediate and not insignificant impact on the global economy. In fact, it is the main reason why we are bracing for a severe global economic slowdown in 2023. The main sub-story in this regard will be how Europe will cope. What we do know is that there is no chance of the EU returning to any kind of meaningful energy relationship with Russia. In my view, following the recent revelations about the lack of evidence that Russia blew up the Nord Stream pipelines, and a failure to even name any alternative suspects, we can only conclude that the EU is having a divorce with Russia on an economic level, which at this point is at least in part enforced from outside the EU. A lack of willingness to name any other potential suspects means that Germany & the EU are unwilling to fight this imposed situation.

As for its effect, the fact that as of November 2022, EU natural gas consumption is down by 24% compared with previous 5-year averages. It means that the EU industrial complex is set to see a massive decline in production volumes going forward, which will eventually become broad-based. At the moment, the most notable industry that has been affected is the fertilizer industry, where ammonia production was down by as much as 70% in 2022. This in turn is having a significant negative impact on farming, with the latest news suggesting that Germany’s pig herds declined by about a fifth since 2020, mostly because of high feed prices. Regardless of how the EU intends to spread the burden of less natural gas consumption, a massive decline in industrial use will occur, and in many cases, there are no viable alternate commodities available for substitution.

This is an important economic story for investors to keep an eye on next year and adjust accordingly. For instance, I previously identified potential winners such as Chesapeake (CHK) as a result of the permanent price floor that US LNG exports to Europe now provide. I also identified BASF (OTCQX:BASFY) as a potential major loser. Overall, most EU investment assets do not look very appetizing going forward. Some exceptions such as upstart Fusion Fuel (HTOO), which is set to start producing green hydrogen hopefully soon, may be an exception, given the massive subsidies it is able to take advantage of.

Further down the road, this may eventually become the investment story of the decade, because I do believe that there is a growing chance of the entire EU project collapsing, with perhaps the strongest members following the lead of the UK, leading the way out. But for now, this does not seem like the investment story of 2023, even though ordinarily this would be something that the markets would be watching with greater attention than the Greek financial crisis in 2010.

Other notable investment topics.

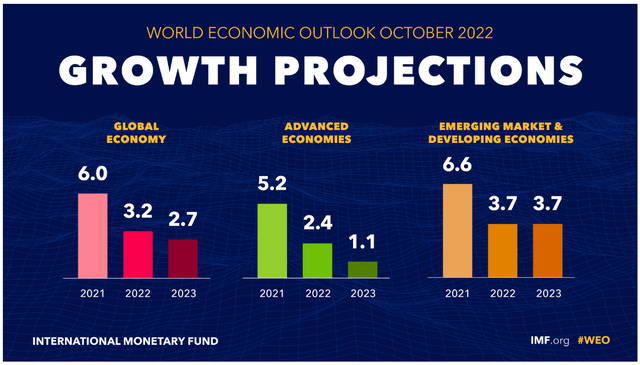

2023 will probably be the year when we will come to terms with the fact that the global commodities market will mostly remain tight for the foreseeable future. Any slack in prices will come at the expense of declining global demand, in other words, recessionary trends. The very fact that even though many leading global economies are expected to shrink in 2023 or are barely growing as has been forecast by the IMF, oil prices are hovering near levels that are around the average price we saw in the past decade, should worry us.

IMF

The inevitable question that arises is what will happen when the global economy will attempt to stage a recovery? Global monthly oil production reached a record high level of production in the fall of 2018, and as of August of this year, it was about 3 mb/d below that level. It is my belief that we are unlikely to ever beat that level of production again. If we will, it will not be by much and it will be very temporary. Other commodity availability issues ranging from food to cobalt will persist. The stagflation thesis stems from the convergence of these two realities, namely the commodity scarcity issues we are seeing surfacing, while global economic growth seems to be entering an era of near-stagnation.

Why China could turn the global economy on its head in 2023 with its response to the semiconductor squeeze.

The screws are being gradually and systematically turned on China’s attempts to develop its own semiconductor and other information technology industries. Even as Taiwan Semiconductor (TSM) is starting to mass-produce 3 nm chips, China’s chip producers are being limited from employing Western technology that can allow them to produce chips below 10 nm. It is thought that these restrictions will serve to produce a bottleneck effect that can strangle China’s entire high-tech industry, relegating the global giant to the role of mostly manufacturing for Western and allied based companies.

As I have been saying for many years now, there is a very obvious danger with the mentality that the Western world can squeeze certain economies through economic sanctions of various designs. This is the case especially when it comes to major economic powers. For instance, the beginning of the economic war on Russia in 2014 has been detrimental to the EU’s own agro-industry. It was thought that Russia’s lack of food product manufacturers, ranging from breakfast cereals to cheese and sausages will leave the Russian population staring at empty shelves for the foreseeable future. In reality, it was a godsend for Russia’s own frail domestic food processing industry, for farmers, as well as for farming equipment producers. Russia’s grocery shelves are increasingly dominated by domestic products, as well as imports from outside the Western World, while the expansion of its farming industry led to Russia becoming a major net exporter of food. Prior to 2014, it was a major net importer.

There are also other examples where economic sanctions pressures have been backfiring, such as the Iran situation, where it is now seemingly not enough of a big deal for Iran to live with the drastic conditions imposed on its economy that it feels the need to compromise in order to get back into the old nuclear deal. Meanwhile, it also seems that their achievements in fields like drone technology have been unjustifiably downplayed. Just a few years back commentators were suggesting that their claims of domestic military development achievements are just empty propaganda. In the past months, Iran’s drones in Russian hands are thought of as a major source of severe danger to Ukraine’s air defenses. Clearly, both cannot be true.

China’s economy is about five times larger than Russia’s & Iran’s combined, both of which are themselves $2 Trillion economies, or $4 Trillion combined. China is far more technologically advanced than either one of them, and it has an industrial base that is globally unrivaled. The idea that

Our assessment that China cannot innovate at a high level may be challenged by recent news & revelations

A few snippets of information that surfaced recently suggest that our assumptions that China cannot technologically overcome our restrictions on its own domestic chip industry may turn out to be a much greater lapse in judgment than prior sanctions decisions. As I warned a few months back in an article on the subject of the rising trend of economic warfare among major nations, our actions may actually be forcing the likes of China to innovate.

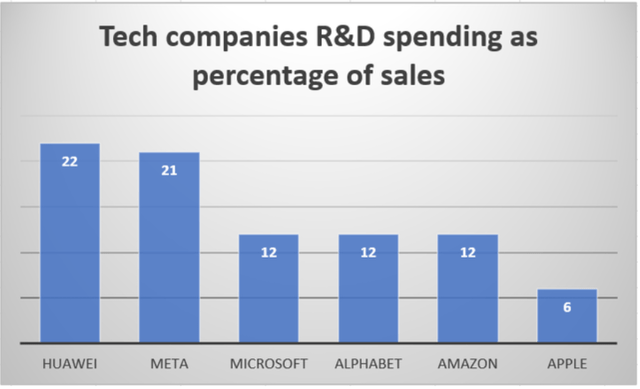

Data sourced from Bloomberg

In 2021 the heavily sanctioned Huawei company outspent most of its major US tech peers in terms of R&D as a percentage of sales. Granted, Huawei suffered some severe declines in sales revenue due to the brutal sanctions regime it was subjected to, starting with the Trump administration in 2018. Having said that, clearly, it decided to not just lie down and die, as it was hoped. The gaping holes in its supply chains left by the tech restrictions imposed on it, which pretty much incapacitated it, had to be filled, and it is increasingly clear, given the recent news that it is set to fill those holes.

It has been revealed just in the past few days that Huawei submitted a patent that shows it may become the first-ever competitor for Dutch-based ASML (ASML), in the field of lithography. A patent is by no means proof of quality and commercial viability. There is a lot we will not know until Huawei will actually apply this patent to real-life economic activities, in other words, it will set up its first manufacturing facilities, based on the patent. It is nevertheless a breakthrough that we did not expect to see any time soon. Assuming that the breakthrough is technically and commercially viable, I expect that we will also see things moving to the production phase a lot sooner than we expect, most likely with the full support of the Chinese government, which will make sure to do everything it can to facilitate the emergence of such production facilities. For this reason, I expect that 2023 is a crucial year, which if it turns out the way I am starting to increasingly suspect, will have far-reaching consequences for the Western investment environment.

My assessment of this subject being more consequential in 2023 in investment implications terms than the global commodities markets or the issue of Europe’s economic woes in the aftermath of its economic divorce from Russia, does not stem from only the Huawei story. In fact, I decided to write this article even before I found out about the potential Huawei breakthrough. About a month ago a Chinese statement of intent surfaced in regard to its intentions to steer its chip industry away from silicon, and switch over to graphene starting in 2025. Graphene has been proven to be far superior in terms of efficiency, making IT devices faster and more energy efficient, which can have huge implications. At the same time, it is thought to be an extremely difficult task to commence commercial production of graphene chips for many technical reasons. The news was predictably met with what seems to have become an automatic, standardized resort to public statements of skepticism, similar to what we have seen elsewhere, as I already highlighted.

The reason I was already committed to writing an article on this subject, even before the Huawei news emerged, is because the implications of China potentially mass-producing graphene chips are far more profound. The Huawei news suggests that at best, China can soon match the Western World and its allies in terms of chip tech and by implication information tech more broadly. That by itself should be worrying, given China’s massive capacity to manufacture.

That manufacturing capacity is now further bolstered by what I regard as perhaps the Western World’s greatest geo-strategic mistake of this century, which was to not take Russia’s interests into consideration, which led to what is now a complete pivot of Russia away from the Western World, towards China and the Developing World more broadly. It basically means that China’s commodities supply chains are now far more secure than Europe’s and perhaps on par with America’s position in this regard. It is yet another lever of potential economic pressure that we lost in relation to the Chinese, even as we are seemingly faced with a year when we might also lose the tech lever.

What to expect in 2023.

With our near-universal assumptions of China’s inability to rise to a high level of innovative sophistication seemingly challenged by emerging signs to the contrary, now the question arises what should expect we to see this year? In order to truly understand, I think that it is worth taking a look at some fundamental differences between our Western society, versus China’s when it comes to economic development within our respective institutional and cultural frameworks. Perhaps the most emblematic recent symbol of it may be France’s ongoing Flamanville nuclear reactor project, which is now about 500% over budget and approaching a decade and a half behind schedule. By contrast, it takes about a fifth of the Flamanville reactor’s project costs and about a third of the time to build the average reactor in China.

There are a number of identifiable culprits that can be used to explain the huge difference in project implementation efficiency between the two examples. There is the labor force’s skills atrophy, as Western society has been less eager to engage in similar project implementation. Perhaps more importantly, there seems to be an institutional divergence taking shape, where in much of the Western World, we are more focused on the process than reaching of the goal itself. In other words, a very strict bureaucracy, demanding very strict adherence to every little detailed step, starting with the bidding process, financing rules, and implementation rules. In China, by contrast, the focus is more on reaching the goal of successfully implementing the project.

For this reason, I expect that even among those who are willing to give China the benefit of the doubt in terms of their innovative achievements in regard to chip manufacturing development, whether in silicon or graphene, there may be some misconceptions in regards to just how fast we may end up seeing actual commercial-scale production. In ordinary circumstances, it seems that most major industrial projects in China may be twice as fast in terms of implementation from the planning phase to completion. China’s drive to catch up to or even surpass the Western World in semiconductors technology is of special importance to China’s economic well-being, thanks to our own actions that are stimulating that urgency. It might therefore be implemented at a surprising speed if their innovative concepts are indeed viable.

China should be expected to pump massive subsidies into these projects this year and beyond. It may further subsidize the production of domestic semiconductors, at least for some years to come. The government stimulus, as well as a more managed approach to organizing China’s supply chains to meet the needs of a new domestic semiconductor industry, devoid of key Western or allied inputs, has the potential to take the global tech sector by storm this decade.

If it is for real, we can expect very visible signs of a massive retooling effort of China’s supply chains, meant to accommodate a fast-paced, massive in size effort to produce domestic Chinese chips, using domestic manufacturing processes. A number of projects to build such facilities should emerge and enter the early stages of execution before the end of the year. I do think that China is aiming to have significant capacities in place to produce high-end chips mostly independent from Western patent and product inputs by 2025, therefore signs of ramp-up should emerge this year, which should wake the global markets to a new impending reality.

Investment implications:

ASML stock dropped on the news of Huawei’s claimed technological breakthrough, even though there is yet to be definitive evidence that we are looking at a real Chinese technological breakthrough event. In the event that I am correct and we will see a significant ramping up of actual projects this year, based on the supposed R&D advances that Chinese companies & researchers seem to have achieved, based on patent filings as well as public statements, the impact on the entire Western tech sector and tech stocks might be quite severe this year. It is especially the case if irrefutable evidence of new supply chains meant to accommodate China’s domestic efforts in this regard will start to emerge.

ASML might be faced with a significant challenge for global market share for lithography equipment that up until now it basically had a monopoly over. The likes of AMD (AMD), Intel (INTC) and Samsung (OTCPK:SSNLF) will face emerging competitors as well, first based in China, where they will emerge or expand quickly, then probably elsewhere as well. If Huawei manages to put together commercial production of its experimental lithography technology at a commercial scale, the sale of such equipment to third parties will probably become a part of its new business model.

Similarly, in the event that Chinese-made graphene chips become a commercial reality by 2025, we will see news of the beginning of such facilities being built in China this year already. For all Western companies involved in silicon-based semiconductor production, it effectively means that there is a chance that their technology will be relegated to low-end electronics industries uses, with graphene taking over on the high-end. For producers of phones like Apple (AAPL) or Samsung, it will mean that some Chinese competitors will emerge, with superior performance, based on graphene chip use, which does perform better, based on past experiments. Even in the absence of Chinese claims of a switch to graphene becoming reality, a return of Huawei in the phone business, with its own silicon chips and other features is sure to have a significant impact on major phone makers.

Chinese car makers may benefit as well, as self-driving technology, based on more powerful computing, driven by graphene semiconductor use, might take a significant leap forward. There is a chance that in the event that China will master this technology, it will turn the tables on us and restrict sales of such chips to our companies. I fully expect them to do that if they succeed. If that will be the case, there is no end in sight to the global industrial implications we are faced with. Tesla (TSLA) may start losing ground to Chinese EV makers on the global market, where increasingly sophisticated features present in Chinese EVs will make them more attractive to consumers. IBM (IBM), and HP (HPQ) may find themselves outclassed in the global PC market. Software makers like Microsoft (MSFT) may find themselves pushed out of some markets, as Chinese electronics may increasingly come with Chinese software. The impact on the global industrial complex is practically limitless, given that most products on the global market today employ increasingly sophisticated electronics and China might be on the verge of leapfrogging the Western World in terms of performance.

Even if the graphene path will fail to pan out, as long as the assumed Huawei breakthrough on lithography turns out to be the real thing, it can still have a massive impact on the global tech sector. It will allow its tech companies to match our tech sector technologically within a few years. Combined with its massive manufacturing capacity advantage, as well as a new reality in terms of raw material supplies security, courtesy of its growing alliance with Russia, the world’s largest net exporter of commodities, China will be able to outproduce on volume and on price.

Some might be tempted to assume that China will not be able to dislocate our tech products and services from the global market, which might serve as the next firewall.

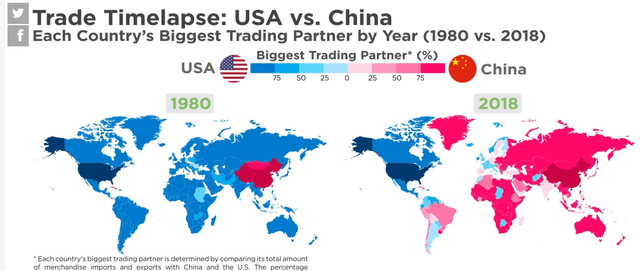

Howmuch.net

In regards to how much of a roadblock the Western World could possibly put up in terms of preventing Chinese tech products from penetrating the global market, this map showing trade reliance across the world on China versus the US provides a clear answer in my view. It would be very hard to prevent China from selling its own tech brand products. Pressures on third-party nations would probably backfire. We already saw in 2022 a lot of pushback against attempts to economically isolate Russia, with complete disregard for the interests of third-party nations.

When China unveiled its “Made in China 2025 strategy”, it became clear that China will never be satisfied to serve solely as the world’s factory, mostly producing non-Chinese products for foreign companies. It freaked much of the Western World as well as some Asian allies out, realizing that China’s rising tech companies could displace many of our own currently globally dominant tech champions. The envisioned solution to the problem was to deprive the Chinese economy of many key technological inputs, that would create a bottleneck effect.

The brutal takedown of Huawei seemed to confirm the effectiveness of such a strategy. As we can see now, it may have backfired, even though it may have slowed down China’s plans by a few years. The original 2025 plan probably envisioned companies like Huawei gaining ground on the global market with partial non-Chinese tech inputs. For instance, the chips used in its Huawei phones would have still been produced by TSMC, with ASML lithography machines. Now it seems that Huawei may still come back as a competitor in most electronics sectors it was previously threatening, but it will also become a competitor to both TSMC and ASML. At least, that is what it looks like based on reports from the end of last year. By the end of this year, we are likely to get confirmation on whether that is the case or not. If so, as investors we should be prepared to also readjust our portfolios, because there are probably few investors out there that do not have long-term positions that will be adversely affected either directly or indirectly. 2023 will be the year when we will most likely find out if the worst of what we feared about China’s 2025 plan will come to pass. In our attempts to stop it, we may have ended up making things much worse than we feared.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.