Shidlovski/iStock via Getty Images

Cassava Sciences (NASDAQ:SAVA) recently presented a chart at the Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases Conference in Lisbon that did not match the chart that it had presented at the Clinical Trial on Alzheimer’s Disease Conference (CTAD) held in Boston last year. This set off a small flurry of speculation as to the reasons for the mismatch; all the way from the benign (different statistical modeling) to the manipulative (missing patient data). In this article, I will explain the reason for the discrepancy between the two charts and what it likely means for Cassava Sciences’ future.

The patient populations are quite similar between Cassava Sciences phase 2b trials and its phase 3 trials, so the results should be similar as well. The wild card is how the FDA [Food and Drug Administration] will respond to these likely readouts. There is a possibility that Cassava Sciences’ simufilam could be approved for those with pre-Alzheimer’s disease. That is why I am not changing my recent hold recommendation.

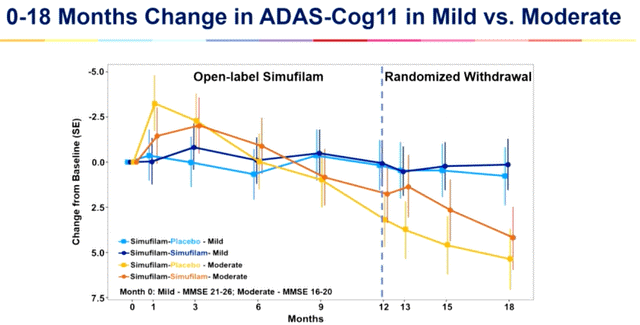

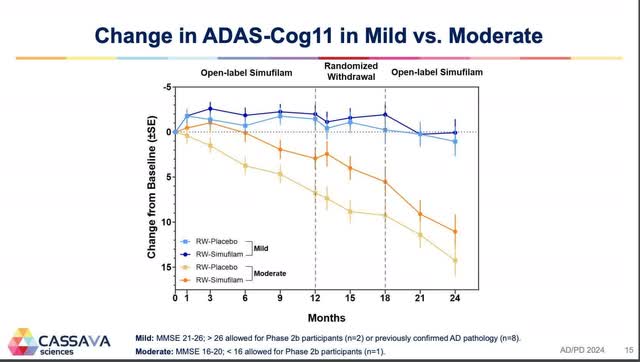

Cassava Sciences has created confusion by averaging the mild Alzheimer’s disease group with other groups. Part of this is not their fault, as the definition they used for mild Alzheimer’s disease in the phase 2b trials (Mini-Mental State Examination range of 21-26) is accepted by some in the scientific community. They did, however, include ten patients whose MMSE scores were higher than 26 (acknowledgment p. 15). Others define mild Alzheimer’s disease as an MMSE score of 21-24. In any case, simufilam kept patients with an MMSE of above 24 near baseline for two years whereas it kept those with an MMSE of 21-24 near baseline for one year. It did little better than placebo for those with moderate Alzheimer’s disease from the beginning.

Cassava Sciences initially reported a 3.2 improvement in Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive-11 scores (later adjusted to 2.4 points) in those with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease at 12 months (press release). This however was in the first fifty patients with mild cognitive impairment/very mild Alzheimer’s disease (ADAS-Cog 15, MMSE of 24.8). When Cassava Sciences released the full data set, the decline at 12 months was 1.54 points (presentation, p. 14). If you exclude those with mild cognitive impairment/very mild Alzheimer’s disease the decline was 2.45 points (I am going to use the term mild cognitive impairment or the abbreviation MCI from now on for simplification purposes).

Cassava Sciences in essence had three different groups who responded to simufilam at 12 months as follows:

50 Mild Cognitive Impairment patients: 15.0 to 12.6 (2.4 point improvement)

83 Mild Alzheimer’s Disease patients: 19.1 to 19.6 (.5 point decline)

83 Moderate Disease Patients: 25.7 to 30.1 (4.4 point decline)

(press release)

After the twelve month trial, Cassava Sciences combined what remained of the initial 50 MCI patients with what remained of the the second group of 50 patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease (76 patients in the “mild group”) and combined what remained of the 33 patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease with what remained of the 83 patients with moderate Alzheimer’s disease (81 patients in the “moderate group”). About half of each group remained on simufilam and half were switched to placebo (presentation).

The averaging of these groups is what produced the chart from CTAD. On the other hand, the Lisbon chart was for those taking simufilam who had mild cognitive impairment and those who had moderate Alzheimer’s disease (the lower lines are for those who were switched to placebo between 12 and 18 months). This second chart shows the true effects of simufilam on these two groups. What is missing from this chart, though, is the effect of simufilam on mild Alzheimer’s disease.

CTAD graph (Cassava Sciences)

Lisbon graph (Cassava Sciences)

When you average the mild cognitive impairment patients with the mild Alzheimer’s disease patients, simufilam keeps this combined group near baseline for 18 months (3 point improvement in those with mild cognitive impairment and about a 3 point decline in those with mild Alzheimer’s disease). Similar to Aricept, simufilam keeps mild Alzheimer’s disease patients near baseline for one year, but then like Aricept mild Alzheimer’s disease patients decline on simufilam similar to placebo (table 3).

When Cassava Sciences said it kept mild Alzheimer’s disease patients near baseline for two years, it meant that it kept mild cognitive impairment patients near baseline for two years (press release).

If the FDA looks at the statistics in a similar fashion (which seems probable based on recent trials distinguishing between mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer’s disease), then simufilam will not be approved for the treatment of moderate Alzheimer’s disease, will probably not be approved for treatment of mild Alzheimer’s disease, and has a good chance of being approved for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment for two years at least.

If this turns out to be the result, the market reaction is difficult to predict. Expectations for simufilam have been declining, but there is still likely to be some disappointment that the drug does not have a significant effect on Alzheimer’s disease. On the other hand, no drug has been approved for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment yet (possible competitor), so this would provide Cassava Sciences with a large, uncontested patient market for a while at least. Cassava Sciences, then, may survive without having a blockbuster Alzheimer’s drug.