Local weather change has just lately been receiving vital and nervous consideration from around the globe. Some nations and areas have adopted carbon pricing reminiscent of carbon taxes and emissions buying and selling as countermeasures towards international warming. Nonetheless, there’s a concern about cross-border carbon leakage when a rustic introduces carbon pricing. Even when carbon emissions lower in that nation on account of carbon pricing, carbon leakage will increase carbon emissions overseas, and in some circumstances even will increase international emissions. Cross-border carbon leakage undermines a rustic’s try and take care of local weather change.

The literature has recognized the next three principal channels of carbon leakage.

- When carbon-intensive items exporters or importers introduce carbon pricing, the world value of fossil fuels falls, which in flip will increase fossil gas consumption and carbon emissions in different nations (e.g. Bohm 1993, Felder and Rutherford 1993, Kiyono and Ishikawa 2004, 2013, Hoel 2005).

- Corporations shift their manufacturing crops from nations with carbon pricing to nations with lax emission laws, thereby rising carbon emissions within the latter (e.g. Markusen et al. 1993, 1995, Kayalica and Lahiri 2005, Zeng and Zhao 2009, Ishikawa and Okubo 2011, 2016, 2017).

- As carbon-intensive items producers in nations with carbon pricing lose their competitiveness, overseas rivals improve their manufacturing, resulting in a rise of their carbon emissions (e.g. Copeland and Taylor 2005, Ishikawa et al. 2012).

Worldwide commerce and overseas direct funding (FDI) exert an essential affect on the channels defined above. In actual fact, many research that analyse the consequences of emission laws from a world perspective incorporate worldwide commerce and FDI. Nonetheless, most of these research don’t think about worldwide transport. Those who handle the interplay between commerce, transport, and the surroundings assume that the freight charges are exogenously given with out an express mannequin of the transport sector (e.g. Cristea 2013, Vöhringer et al. 2013, Shapiro 2016).

Moreover, the quantity of carbon emissions created by worldwide transportation itself is simply too massive to disregard. In keeping with the Worldwide Maritime Organisation, worldwide transport emitted roughly 920 million tonnes of CO2 in 2018, surpassing Germany’s nationwide emissions (the sixth-highest emission on the planet). The Paris Settlement, which got here into impact in 2016, didn’t set particular targets for emissions from worldwide transportation. Just lately, leaders of a number of nations and trade associations delivered a sequence of statements concerning international warming countermeasures associated to worldwide transport:

- The Worldwide Civil Aviation Group (ICAO) began the Carbon Offsetting and Discount Scheme for Worldwide Aviation (CORSIA) in 2021.

- In Might 2021, the EU introduced that worldwide aviation and delivery will likely be included within the Emissions Buying and selling System (ETS).

- In September 2021, the US authorities introduced a objective to scale back aviation-related international warming gasoline emissions by 20% by 2030.

- In October 2021, the Worldwide Air Transport Affiliation adopted a goal of nearly zero international warming gasoline emissions in 2050.

- At COP26, 22 nations signal the Clydebank Declaration to create zero-emission delivery routes.

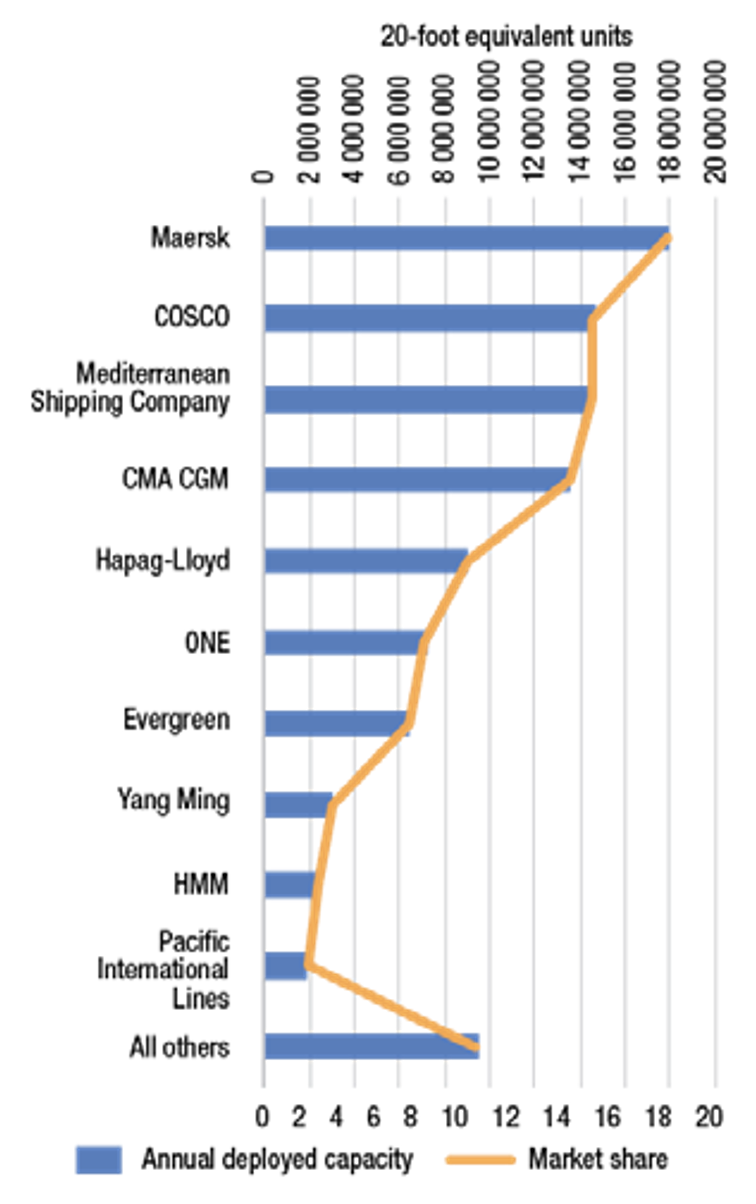

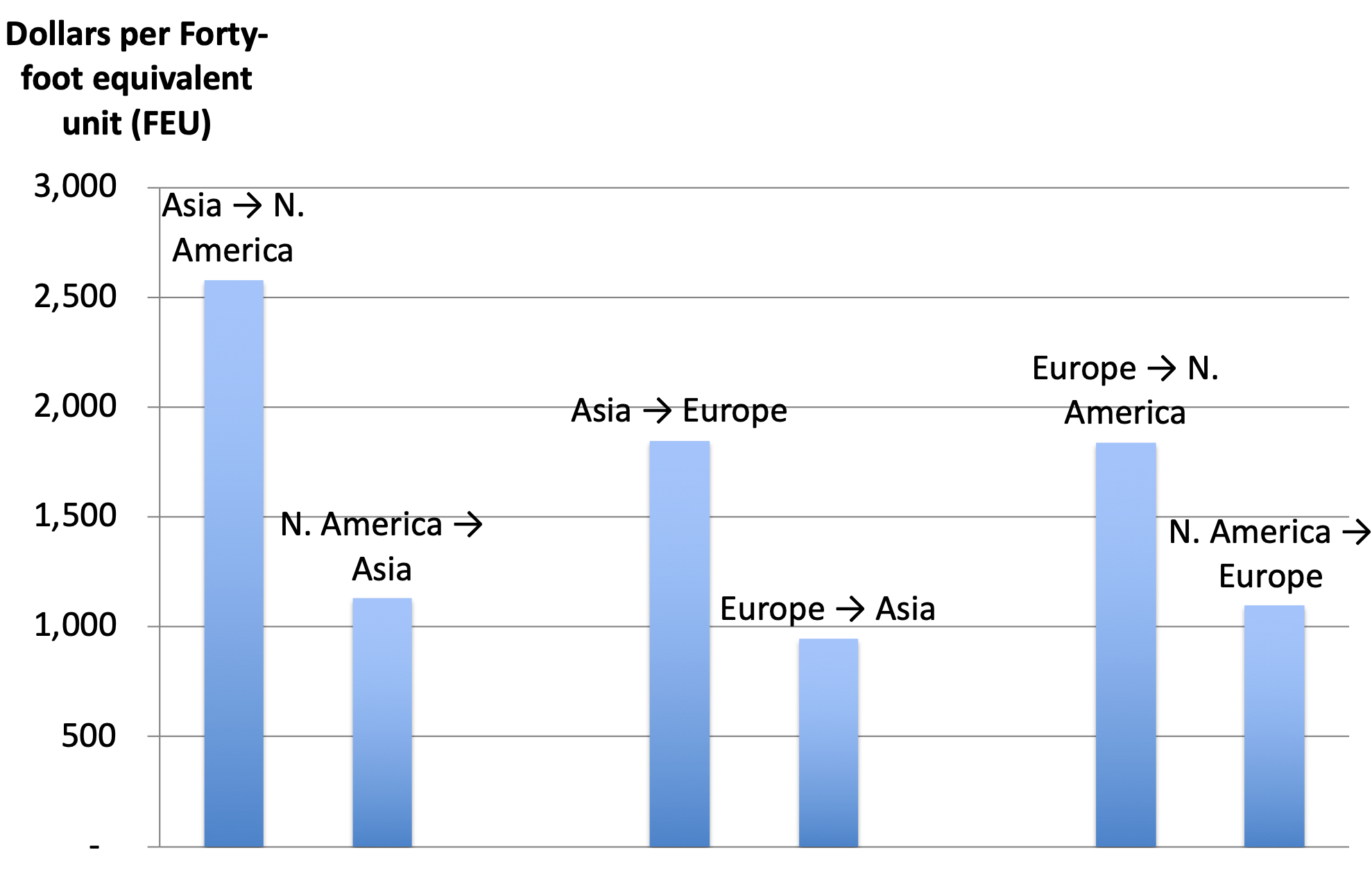

In a latest paper (Higashida et al. 2021), we theoretically analyse the impact of unilateral carbon pricing on carbon emissions from manufacturing, consumption, and worldwide transport by explicitly modelling the worldwide transport sector. Our mannequin is predicated on the endogenous transport value literature, which has discovered that the worldwide transport sector is very concentrated, with transport corporations having market energy (Hummels et al. 2009). The transport corporations cost uneven freight charges on delivery in several instructions on the identical commerce route topic to the backhaul downside. The backhaul downside arises when the transport agency’s delivery capability just isn’t utilised on the most stage on the backhaul due to asymmetry in commerce volumes. Notably, endogenous dedication of worldwide transport volumes and costs explains a brand new mechanism of cross-border and cross-sector carbon leakage.

Determine 1 High 10 deep-sea container delivery traces, ranked by deployed capability and market share, Might 2020

Supply: UNCTAD Evaluation of Marine Transport 2020, Determine 2.9.

Determine 2 Inter-regional contract freight charges, 2018–2020

Supply: UNCTAD Evaluation of Marine Transport 2020, Desk 3.1.

The effectiveness of carbon pricing is dependent upon the presence or absence of a backhaul downside.

If the exports from nation A to nation B (the fronthaul) exceed these from nation B to nation A (the backhaul), the backhaul downside is current. The equilibrium freight price on exports from B to A is then impartial of the marginal prices of delivery (Ishikawa and Tarui 2018). Due to this fact, despite the fact that carbon pricing in delivery raises the efficient marginal prices of delivery, it impacts the freight charges in an uneven method when the backhaul downside is current. Below this example, carbon pricing on the transport sector reduces the fronthaul however impacts neither the backhaul nor the related emissions. We present that unilateral carbon pricing on items consumption is efficient. Nonetheless, carbon pricing on items manufacturing leads to ‘optimistic’ cross-border carbon leakage: nation A’s carbon pricing on manufacturing lowers the fronthaul however will increase the manufacturing in nation B and the backhaul, and therefore generates optimistic cross-border carbon leakage. These modifications are standard, however the endogenous improve within the freight price mitigates them, which means the behaviour of transport corporations weakens cross-border carbon leakage.

In contrast, if the fronthaul equals the backhaul (i.e. the backhaul downside is absent), we discover that each cross-border and cross-sector carbon leakage attributable to carbon pricing might be ‘damaging’. In different phrases, carbon pricing might be exceptionally efficient as a result of carbon pricing on a sector in a buying and selling nation might scale back emissions not solely from the goal sector but in addition from different sectors together with these in different buying and selling nations. For instance, carbon pricing on delivery will increase freight charges for each instructions, resulting in the lower in each fronthaul and backhaul. Thus, emissions not solely from the transport agency but in addition from the manufacturing corporations can lower, implying that damaging ‘cross-sector’ carbon leakage can happen. This commentary identifies a brand new supply of carbon leakage as a result of endogenous transport prices. We additionally present that if the backhaul downside is absent, any carbon pricing is efficient as a result of the worldwide greenhouse gasoline emissions essentially lower.

Our evaluation additionally signifies that carbon pricing on worldwide transport might not scale back general trade-related emissions as soon as we think about the interaction between endogenous transport prices and producers’ selections on FDI. Confronted with a producer which will interact in horizontal FDI (i.e. in native manufacturing), the service might deter it strategically as a result of the demand for transport decreases if horizontal FDI doesn’t induce any commerce in intermediate inputs. Furthermore, even when the service accommodates such FDI, it prefers FDI with a single overseas plant to FDI with two crops (a home and overseas plant) as a result of there isn’t a demand for worldwide transport with two-plant FDI. Thus, the service has an incentive to induce single-plant FDI. These strategic strikes by the service additionally have an effect on the worldwide emissions.

These findings observe from our theoretical framework, which addresses the interlinkage between commerce, transport, and surroundings by contemplating the transport sector explicitly. They point out one other good thing about complete regulation of emissions from each manufacturing (or consumption) and transport.

We argue that it is very important perceive the market surroundings of the worldwide transport sector when designing carbon pricing. Particularly, the backhaul downside impairs not solely the effectivity of transportation but in addition the effectiveness of carbon pricing. The effectiveness of carbon pricing will improve if insurance policies might be taken to get rid of the backhaul downside concurrently carbon pricing.

Editors’ word: The primary analysis on which this column is predicated first appeared as a Dialogue Paper of the Analysis Institute of Economic system, Commerce and Trade (RIETI) of Japan.

References

Bohm, P (1993), “Incomplete worldwide cooperation to scale back CO2 emissions: Different insurance policies”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Administration 24(3): 258-271.

Copeland, B R and M S Taylor (2005), “Free commerce and international warming: A commerce concept view of the Kyoto protocol”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Administration 49(2): 205-234.

Felder, S and T F Rutherford (1993), “Unilateral CO2 reductions and carbon leakage: The implications of worldwide commerce in oil and primary supplies”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Administration 25(2): 162-176.

Higashida, Ok, J Ishikawa and N Tarui (2021), “Carrying Carbon? Damaging and Constructive Carbon Leakage with Worldwide Transport,” RIETI Dialogue Paper Collection 21-E-102.

Hoel, M (2005), “The triple inefficiency of uncoordinated environmental insurance policies”, Scandinavian Journal of Economics 107(1): 157-173.

Hummels D, V Lugovskyy and A Skiba (2009), “The commerce lowering results of market energy in worldwide delivery,” Journal of Improvement Economics 89: 84-97.

Ishikawa, J, Ok Kiyono and M Yomogida (2012), “Is emission buying and selling helpful?”, Japanese Financial Evaluation 63(2): 185-203.

Ishikawa, J and T Okubo (2011), “Environmental product requirements in north-south commerce”, Evaluation of Improvement Economics 15(3): 458-473.

Ishikawa, J and T Okubo (2016), “Greenhouse-gas emission controls and worldwide carbon leakage by commerce liberalization”, Worldwide Economic system 19: 1-22.

Ishikawa, J and T Okubo (2017), “Greenhouse-gas emission controls and agency areas in north–south commerce”, Environmental and Useful resource Economics 67(4): 637-660.

Ishikawa, J and N Tarui (2018), “Backfiring with backhaul issues: Commerce and industrial insurance policies with endogenous transport prices,” Journal of Worldwide Economics 111: 81-98.

Kayalica, M Ö and S Lahiri (2005), “Strategic environmental insurance policies within the presence of overseas direct funding”, Environmental and Useful resource Economics 30(1): 1-21.

Kiyono, Ok and J Ishikawa (2004), “Strategic emission tax-quota non-equivalence below worldwide carbon leakage”, in S Katayama and H W Ursprung (eds), Worldwide Financial Insurance policies in a Globalized World, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Kiyono, Ok and J Ishikawa (2013), “Environmental administration coverage below worldwide carbon leakage”, Worldwide Financial Evaluation 54(3): 1057-1083.

Markusen, J R, E R Morey and N D Olewiler (1993), “Environmental coverage when market construction and plant areas are endogenous”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Administration 24(1): 69-86.

Markusen, J R, E R Morey and N D Olewiler (1995), “Competitors in regional environmental insurance policies when plant areas are endogenous”, Journal of Public Economics 56(1): 55-77.

Zeng, D Z and L Zhao (2009), “Air pollution havens and industrial agglomeration”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Administration 58(2): 141-153.