Donald Trump’s plan for a wall across the American southern border is one of the most controversial policy proposals in American history. Along with Trump’s usual dose of falsehoods and anti-immigration fear-mongering, the opioid crisis quickly became a favorite talking point to support his flagship policy, specifically the increase in deaths from fentanyl overdoses. Trump lauded the wall as a sure fire way to halt drugs from crossing over the border, even though “U.S. statistics, analysts and ongoing testimony at the New York City trial of drug kingpin Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman show that most hard drugs entering the U.S. from Mexico come through land border crossings staffed by agents, not open sections of the border.”

Of course, these are poor solutions, because they ignore the overdose crisis entirely, and simply rehash war on drugs rhetoric. The suggestion these policies make is that America needs to take its drug problem even more seriously, as severe drug possession and trafficking penalties are not enough. The “tough on drugs” policy over the last 60 years has failed to deliver America free from drug addiction, and has instead tied America’s drug crisis far beyond the southern border, to homelessness, destabilization of the family unit, income inequality, institutional distrust, worsening mental health, and the criminalization of poverty. But if the war on drugs isn’t the solution, then what is?

Why has the drug epidemic increased in scale even though the nation has made such progress in economic growth, education, and crime since the 1970’s? Is American capitalism to blame for the drug epidemic? Has America given up on the least of us? Sam Quinones joins EconTalk host Russ Roberts to discuss the link between drug addiction and homelessness, the economics of drug cartel monopolies, and the possible solutions to the opioid crisis.

An important theme Quinones stresses is the sheer scale of the drug crisis. He argues that this wave of the drug epidemic is distinct from the problem faced in the 1970’s with its proliferation of drugs, specifically fentanyl and meth. Further, the epidemic is affecting the entire nation, not just pockets of certain urban areas. The crisis has shifted to devastating suburban and rural areas, and has become so rampant that Quinones believes that the overdose death toll is significantly undercounted by at least 20-30%. The COVID-19 pandemic brought this problem even more into the spotlight, as homelessness, suicides, and deaths from despair skyrocketed.

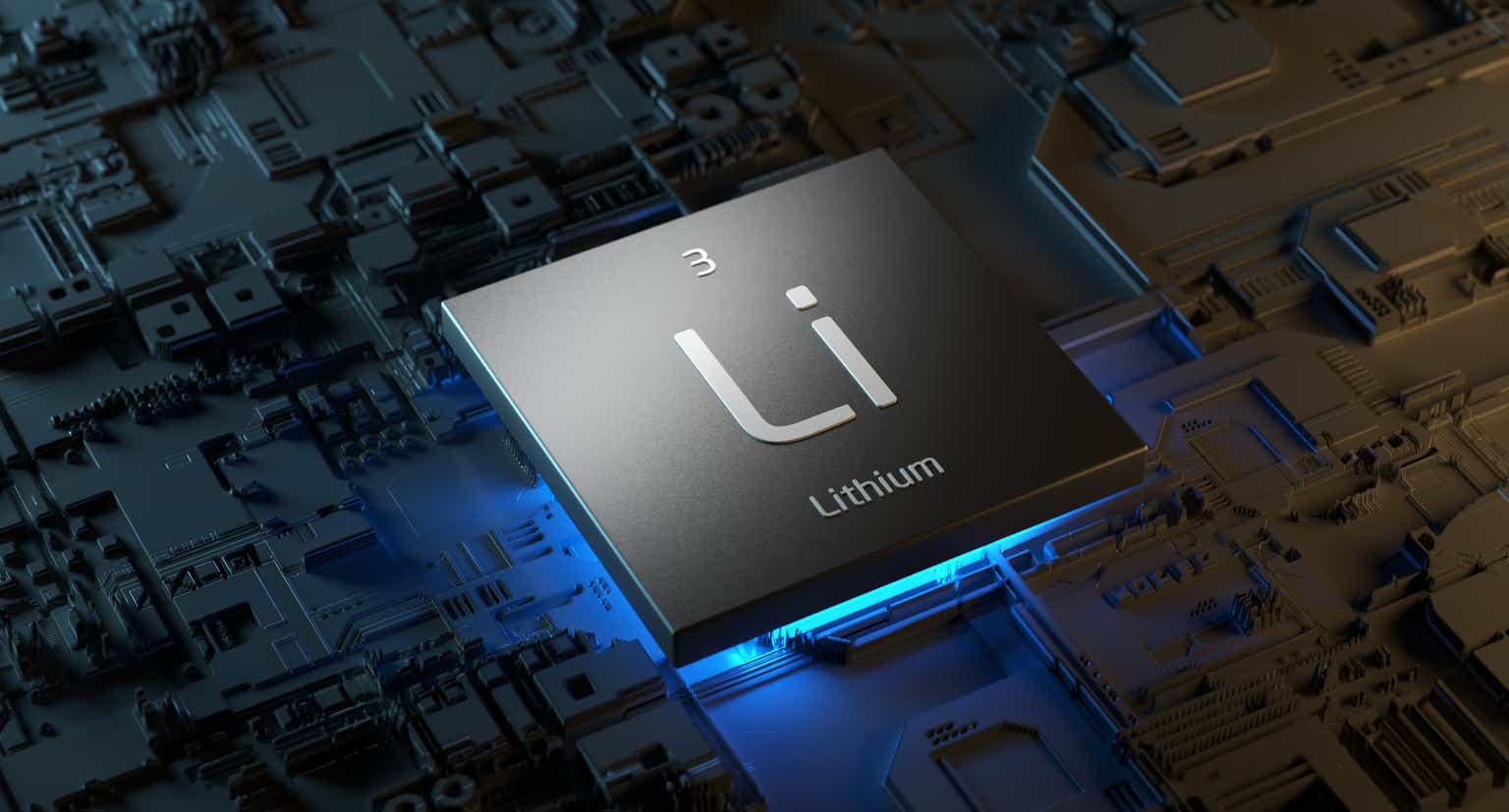

One of the reasons overdose is so common is because of the rise of fentanyl. Quinones explains that fentanyl really only began to filter into American drug markets in the mid-2000’s, soon killing hundreds of thousands of people in a “big loop of a death curve.” So why is fentanyl so deadly? Mostly, unintended consequences. Roberts describes how fentanyl began as a fantastic drug for surgery, as it gets to the brain very quickly and also wears off very quickly. The rapid high of fentanyl also made it a miracle drug for cartels, and they quickly introduced it into other drugs. To Quinones, this innovation in the drug market was inevitable.

But, the buyers of cocaine and methamphetamine, because those drugs don’t have the same kind of withdrawals that opioids have, the buyers of those things are not daily, desperate, almost religiously daily buyers of this stuff. Right? They’re the occasional users–‘Oh, I’ll buy it for the weekend,’ or that kind of thing. If you add fentanyl to the mix, what you eventually are going to get is an opioid-addicted customer, almost as if it were a heroin addict; and that customer is going to buy from you every single day. Maybe sometimes more than once a day.

The war on drugs is also complicit in the incentivization of drug dealers. As elucidated by Benjamin Powell in an article for Econlib, the war was fought on the supply side, as it attempted to cut off the sales of drugs. However, all this did was further empower cartels through increased drug prices and monopolization, “Because the demand for drugs is not price-sensitive, each “victory” in the war on drugs enhances drug dealers’ revenue, making future decreases in supply all the harder to achieve. It is no accident that the number of annual drug-related deaths in Mexico almost quintupled from 2,300 in 2007 to 11,000 in 2010.”

Quinones and Roberts discuss this same topic in reference to the Mexican government’s crack down on methamphetamines. The Mexican government outlawed possession of the key ingredient in methamphetamine, ephedrine; however, the adaptability of methamphetamine producers allowed for virtually endless strains of the drug. Drug kingpins being killed by the Mexican government simply allowed for further consolidation of the market for the remaining cartels, causing drug prices to rise, and creating more of an incentive for cartels to increase production.

You can’t regulate it, the way you could–if you have only one chemical that’s kind of like the bottleneck, government can regulate that. Pay close, close attention to it. And, basically you have a difficulty going forward with it. And, that’s what happened with ephedrine. With this stuff, if you use one way to make P2P and they crack down on some of those chemicals, well, you can find another. And, it turns out according to organic chemists and DEA [Drug Enforcement Agency] chemists I’ve spoken with, that there’s really almost–not to say there’s no end to the numbers of ways you can make P2P, but there are many, many ways. And, they all use very common chemicals, chemicals that are common in the industrial world and legal industrial processes.

Why is America addicted? Quinones and Roberts concur that the drug epidemic is not a problem in itself, it’s more of a symptom to the true disease: people are lost. Quinones makes this point by laying the blame on American capitalism, as to him, “Corporations behave like traffickers and traffickers behave like corporations.”

And so, initially, I thought this was just a story about the enormity of the supply and the prices dropping. In Kentucky, where they before were doing that Sudafed pill reduction method–known as ‘shake and bake,’ is what they used to call it–now, that’s gone. All of that is just gone. All those little suppliers, like what Walmart did to Main street in America, that’s what Mexican meth does to all those small suppliers.

To Quinones, monopolization through corporatization has created addiction through destitution. Americans put out business by large multinational corporations have almost nowhere else to turn but to sell drugs to get by financially and use drugs to cope with the loss of their life’s work. Walmart’s success is just one example of America choosing prices over people, as small businesses on main street are far more important than just jobs, as they provide a source of community and social cohesion. In Quinones’ view, monopoly is inevitable.

A perfect example, I think, of what’s happened to our country is in the big box stores. Primarily Walmart. You know? Walmart came in and destroyed a lot of mom and pop main streets, locally owned folks, people with lonely stores for sometimes generations. I think the whole opioid problem is largely rooted in part in that.

Roberts disagrees with the indictment of capitalism. He emphasizes two areas of social life where Americans have typically found meaning and community: family and religion. Roberts believes that the decline in religious belief and the growing presence of divorce and people choosing not to get married is the true culprit of American drug addiction.

So, two places where people found a sense of meaning and community–either their local church, synagogue, or mosque, or their nuclear family, their children, and their spouse–those are increasingly less common. And, I would suggest that we have not been able in America to find a way to cope with that social disruption…The drug usage that we’re talking about in this episode and the rise in depression that Johann Hari talks about, these are coming from a desperate, inadequate way to satisfy the basic human needs of belonging, of loving, of connecting.

The theme of social isolation and dissolution is a common one among EconTalk episodes, as this episode “forms something of a trilogy with recent episodes with Johann Hari on Lost Connections, and Noreena Hertz on The Lonely Century,”

Quinones ends up ardently agreeing with Roberts in this segment of the argument. Both think that the erosion of family and religious institutions has left few social institutions to care for “the least of us.” This is the reason he titled his book The Least of Us. The dissolution of community has produced apathy towards social problems, and an implicit refusal to solve them.

Roberts is intrigued by this, and defends capitalism by saying the system itself is morally neutral, and is very good at giving people what they want, so the true question to him is why do so many people seem to want a life of opioid addiction?

S what are the solutions? To Quinones, focusing on the least of us is necessary. Each individual has a role to play in curing an addicted America

And, what must our response be then? Well again, the book’s title, The Least of Us, seems to me to be the appropriate one, where we return to local–focus on our neighbors, focus on our streets, focus on our churches, synagogues, mosques, what have you. Focus on our local business, patronize our local business. Get outside, for God’s sake.

…we need to understand the power of walking down Main Street and seeing the guy who fixed your shoes, you know, a year ago, and say, ‘Hey, how are you doing?’ Be a part of a community.

Quinones’ last point is one of hope. Quinones and Roberts end with agreement that incremental steps to rebuild one’s community is the best place to start.

I had some questions [below] while listening to this episode. We hope you’ll share your thoughts with us as well!

1- The relationship Quinones is discussing between addiction and homelessness is interesting. Does addiction cause homelessness, as Quinones believes, or does homelessness cause the addiction problem? How do factors such as high housing costs, disabilities, the failed war on drugs creating institutional poverty, and systemic racism affect homelessness? How would policies such as drug decriminalization and rehabilitation combined with transitional housing for the homeless impact the link between homelessness and addiction?

2- A theme throughout the episode is unintended consequences. How can unintended consequences from morally neutral things be avoided? Legality doesn’t seem to be the answer, so how can civil society and the marketplace solve its own problems? How can the destruction in creative destruction be minimized?

3- Healthcare policy has a definite role to play in this discussion. How have policies such as certificate of need laws and restrictive scope of practice laws affected the ability of drug users to receive care? How would expansions to the social safety net such as with a public option healthcare system fare in alleviating the opioid crisis?

4- Quinones states that the cartels producing the fentanyl don’t care how deadly it is because of their position up the supply chain, they’re disconnected from the harm that a customer’s death from an overdose would cause to an individual seller, and this is why fentanyl continues to kill people. Why would the individual sellers themselves continue to sell such a deadly drug with a margin of error so low?

5- The thread of discussion mentioned in the above question led to Roberts’ question of why customers would ever willingly purchase a stronger version of meth that has far worse side effects, such as paranoia and a larger chance of overdose. In his words, “Why would anyone take this stuff? It turns you into this paranoid person who can’t hold a job. Now, I understand, once you’re addicted, you’re in trouble. But, how do you move from that to that world?” How does Quinones answer this question, and to what extent do you agree with his explanation?