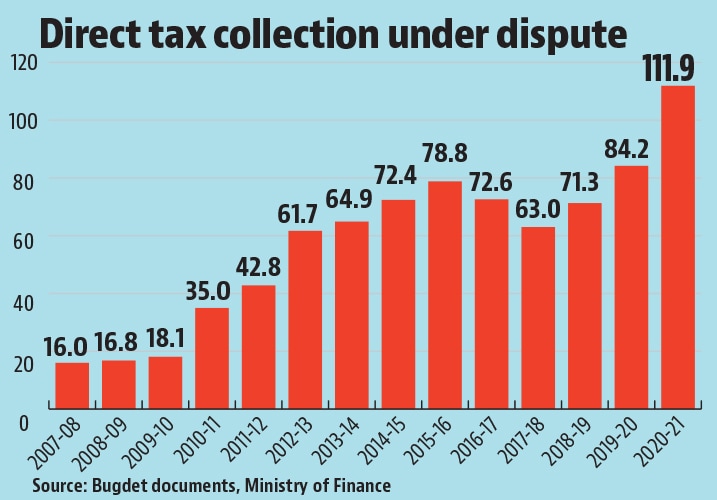

As finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman prepares the Union Budget for 2023-24, it is worth recalling her Budget speech from 2019, when she quoted Tamil poet Pisiranthaiyar’s allegory for government-taxpayer relations, “A few mounds of rice from paddy, that is harvested from a small piece of land, would suffice for an elephant. But what if the elephant itself enters the field and starts eating? What it eats would be far less than what it would trample over.” An imaginative mind might see the shape of an agitated elephant in the adjoining chart, which plots direct tax collection under dispute at the end of a year, as a percentage of the gross direct tax collection during that year. The year-on-year change reflects the net change during the year, as some disputes get resolved, while others get instituted.

At the beginning of the previous decade, disputes rose rapidly, moderating slightly in 2016-17 and 2017-18, probably due to amnesty schemes. But in 2018-19 and 2019-20, the elephant raised its trunk in hunger. To make matters worse, in 2020-21, low revenue receipts, a rise in disputes, and the slow resolution of disputes pushed the stock of direct tax collection under dispute to a level higher than the flow of direct tax revenues in the year. The spike in the early 2010s was mostly on account of disputes in personal income tax, but the recent spike is seen in both corporate and personal income tax.

What makes this rise in disputes troubling is that the administration seems unsuccessful in winning most of them. OECD’s biannual report on tax administration reports the percentage of cases resolved in favour of the administration in leading jurisdictions — that is, cases in which the administration was successful in more than 50% of the issues contested. In 2020, the average for the 47 jurisdictions included was 66%. In India, this was only 7.9%. This disparity has persisted for many years, and India has consistently ranked at the bottom of the list of countries on this count.

While the poor success rate could be partly explained by a failure to fight these disputes properly, the extreme rarity of success suggests the administration may be making some unreasonable demands. It is worth considering why this may be happening. First, the rise in disputes has corresponded with periods of economic slowdown. Early in the 2010s, direct tax disputes increased while a fledgling, stimulus-driven recovery from the global financial crisis was underway. The recent rise also corresponds with a growth slowdown. Economic problems may have translated into low tax collection, and under pressure to deliver revenue targets, the tax authorities made some unreasonable demands, triggering disputes that they lost.

Second, the rise in disputes also corresponds with diluting checks and balances in the law that constrains the actions of revenue authorities. In 2017, the income tax law was amended to weaken the checks on tax authorities. These include not requiring the tax authorities to disclose the reasons for conducting or expanding searches and seizures, even to the appellate tribunal; empowering the officer conducting the search and seizure to attach property for up to six months with the prior approval of senior officers; reducing the seniority level of the officer who can call for information for any inquiry or proceeding, among others.

Third, the fiscal context may also create pressures to make excessive direct tax demands. The government has large, committed expenditures but has, in most years since 2008-09, registered weak performance in collecting indirect taxes, non-tax revenues (for example, dividends and spectrum auction), and non-debt capital receipts (primarily, disinvestment receipts). Since 2015, states’ share of the Union government’s tax pool has also increased. There also seems to be an unwillingness to increase indirect taxes, except through duties on petroleum products, depending on crude oil prices. It seems administratively easier to make additional demands for direct taxes than other revenue receipts.

Finally, the rhetoric of political leadership in the last few years suggests they suspect large-scale tax evasion. This might have translated into political pressure on the tax administration, which then had to appear to go after tax evasion. In 2020, additional assessments raised from audits corresponded to 44.1% of tax collections, while the average for the 51 countries that reported this information in the OECD report was just 5.2%.

The Economic Survey of 2015-16 found India’s direct tax collection is consistent with other countries at this level of income. India’s income tax collection is much higher than the average for countries with its per capita income. So, the expectation from direct taxes might be built on false assumptions.

The allegory of the elephant and farmer must include a mahout riding the elephant. When and how to exercise the elephant’s power is a matter of the mahout’s practical wisdom in understanding what is in the elephant’s (and the mahout’s) long-term interest. If the State goes too easy, taxpayers may take advantage, but if it becomes too draconian, it could have a chilling effect. The powers of tax authorities are the Sword of Damocles dangling over all individuals and enterprises. They can disrupt businesses and harm personal reputations, but they can eventually hurt the government’s ability to mobilise resources.

In recent years, the government has tried to reduce disputes, mostly through dispute-settlement schemes. However, it is also important to prevent unnecessary disputes from arising in the first place. While the budget is primarily about raising and deploying resources, decisions regarding revenue administration and expenditure management systems are also important. The finance minister should consider whether the government’s revenue-mobilisation strategy and its approach to the administration of direct tax are consistent with India’s investment and growth ambitions and how the tax administration’s incentives can be structured so that unnecessary disputes do not arise.

Suyash Rai is deputy director, Carnegie India The views expressed are personal

(A version of this essay was previously sent in Carnegie India’s Ideas and Institutions newsletter)