It’s a fashion of late to compare the UK with Italy. Because yields on their government bonds are at similar levels, commentators have been keen to claim that Britain has became as profligate as the southern pizza, pasta and mafia economy.

Tory MPs are in disarray, and Liz Truss has become the human equivalent of Larry the cat, living in Downing Street but wielding no power. Things are turning ever more Britalian: https://t.co/Wf26N0kFPv pic.twitter.com/c1KoKtsMfu

— The Economist (@TheEconomist) October 20, 2022

But fiscal profligacy is more a reality for the UK than it has been for Italy over the last twenty years.

UK gilt prices dived on the outgoing prime minister’s announcement of large unfunded tax cuts. Drastic U-turns on nearly all the promises, a return to austerity and a record-quick defenestration have stabilised markets but left reputations shredded.

Meanwhile, Italy is waiting for its next finance minister following the election victory last month of Giorgia Meloni’s arch-conservative coalition. Whoever gets the job will be taking control of a government primary budget excluding debt interest payments that has been in surplus for nearly two decades.

This is not the case for the UK, which has recorded a deficit for most of that period. In fact, without interest payments on government debt, Italy has been running a budget surplus similar to that of Germany. It has showed much more frugality than the UK, and of the average of the most industrialised countries.

Today’s UK fiscal similarities would probably be closer with Italy’s fiscal choices in the 1980s, when rapid increases in government spending were not matched by corresponding rises in revenues, resulting in a surge in government debt.

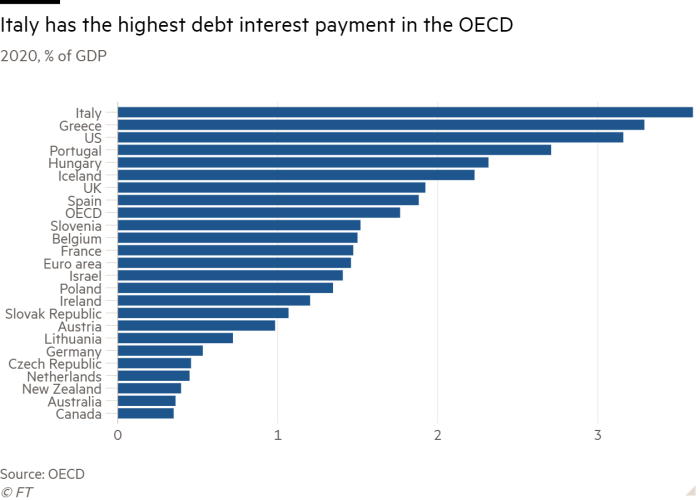

The accumulated government debt still weighs on Italy’s fiscal and economic outlook via the highest payments in the OECD. Coupled with the need for structural reform, Italy’s economy has largely stagnated for the last two decades. This is what is risky about Italy for investors, not recent fiscal profligacy.

Not convinced? Here’s Bert Colijn, senior economist at ING:

The concerns in financial markets about the UK stem from a very accommodative fiscal stance, despite budget deficits already being high and a trade deficit on the back of that,” he said. “This stands in sharp contrast with Italy, which suffers from high legacy debt from the 1980s and 90s, while they have actually delivered primary fiscal surpluses for most of the past two decades.

This means that “Italy has a structural problem of low economic growth and high debt, while the UKs concerns seems mainly related to the very expansionary budget proposals,” said Colijn.

Nicola Nobile, economist at Oxford Economics, agrees. Italy’s problem is “mainly a legacy of the previous accumulated debt as well as a problem stemming from lacklustre growth.”

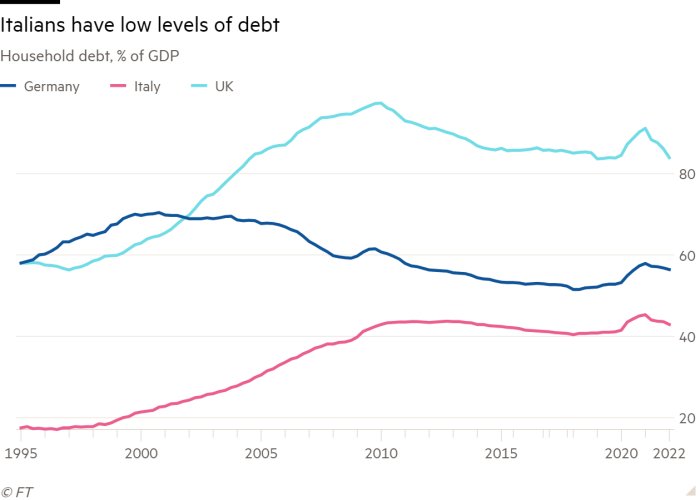

Even Italians households do not live beyond their means. Italy’s households have one of the lowest debt-to-GDP ratios among all advanced economies, well below that of the UK and even lower that of Germans.

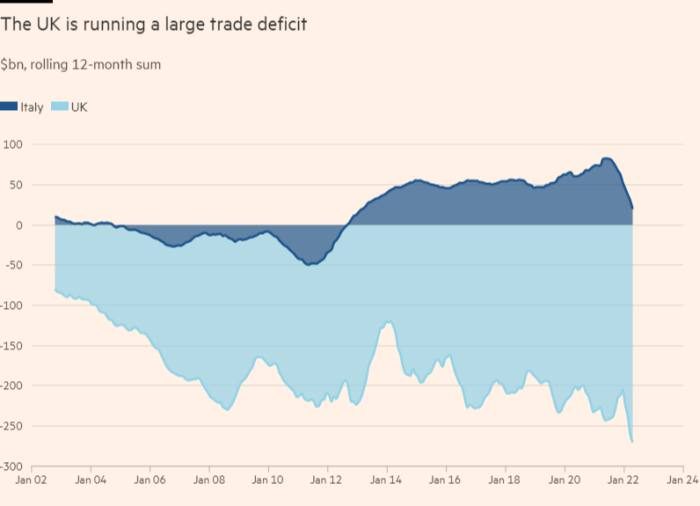

Like the UK, Italy’s economy is struggling with weak domestic demand. But its businesses are successful exporters running a goods exports surplus for the last decades. The UK is running one of the largest current account deficits among advanced economies adding uncertainties for investors.

In summary, rather too many commentators have preso lucciole per lanterne.